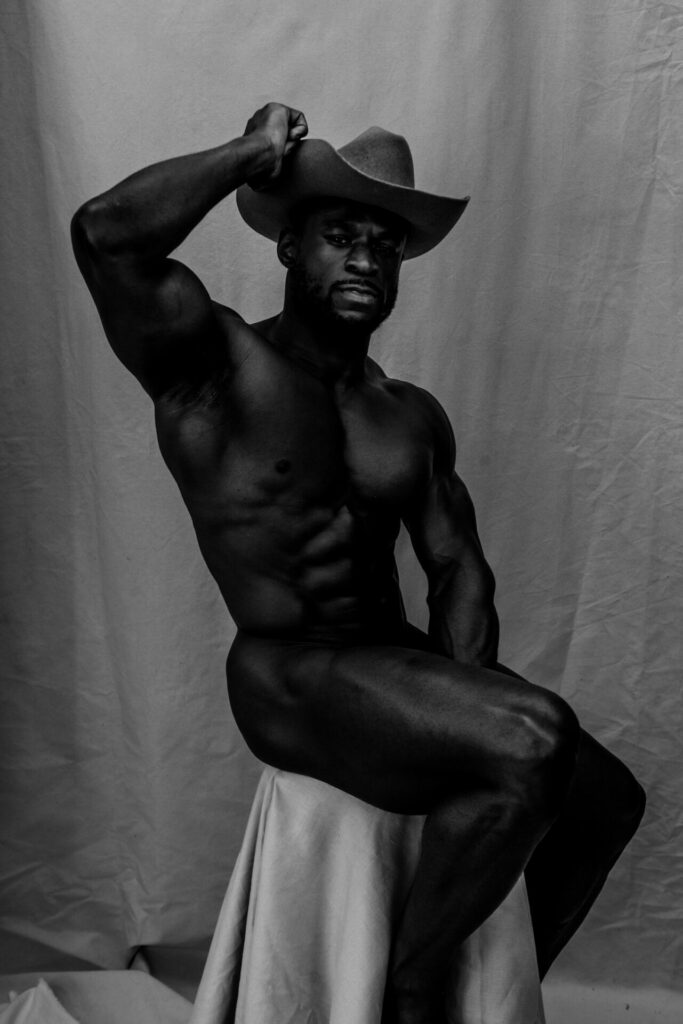

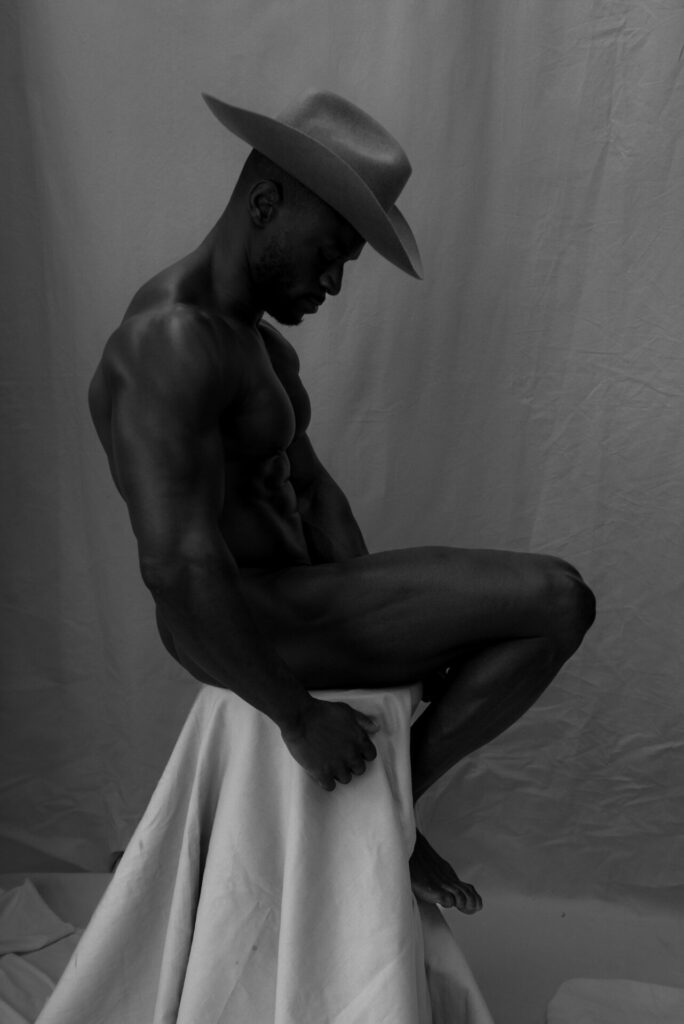

Black in porn: Leveraging stereotypes, monetising desire, and liberation in autonomy

"We’re not seen as human but rather as someone to fulfil their fantasies" says Cody.xxv, an OnlyFans content creator on his identity in content creation

In an era where perceived intimacy is streamable, desire monetised, and bodies endlessly consumable, gay porn remains a potent mirror – and magnifier – of society’s contradictions. The digital age has blurred the line between fantasy and reality, reframing sex work as both personal liberation and public performance. But for Black gay men in the porn industry, that mirror often reflects a distorted and deeply racialised image.

In traditional porn, studios have banked on race-fuelled fantasy for decades.

OnlyFans has merely decentralised the business model, not the bias. In 2024, PornHub, the world’s most popular porn site, issued its annual report of the platform’s most searched porn trends, with Rhyheim Shabazz ranking as the top searched Black performer and five overall.

“They love the ‘Black top, white bottom’ dynamic” – Peter, a performer, on racial dynamics in gay porn

Peter, a US-based performer who entered gay porn in 2004 and now controls his own content empire, says: “They love the ‘Black top, white bottom’ dynamic. Thuggish, aggressive scenes, that’s where the money is. Personally, I have no issue with it. It’s just good business.”

From production-house porn to the creator-led chaos of OnlyFans, Black men are simultaneously exalted and dehumanised. Our bodies, fetishised. Their performances, commodified. Their autonomy? A work in progress.

“I had made a name for myself in the industry,” says Peter*. “I decided to set up my own business, and an OnlyFans. I have total control now. In mainstream porn, you’re asked to be ‘comfortable,’ but actors rarely have full choice.”

His transition to autonomy is not uncommon. As the stigma around sex work recedes, nudged along by the omnipresence of explicit content on platforms like X and Instagram, Black performers are reclaiming space in an industry that has long profited from their radicalisation.

But even in this apparent liberation lies a tension: control doesn’t necessarily equal freedom.

“We all live under capitalism,” says David*, a UK-based porn actor. “None of us can claim full autonomy over our physical selves, whether we choose to go into sex work or not.” He, like others interviewed, admits that while his Blackness is in demand, it rarely equates to respect.

When I ask Peter if he worries about perpetuating stereotypes, he shrugs. “I never thought much about it. I enjoy it. It makes me money. I’m not here to fix people.”

But what if those people are forming opinions and relationships based on what they see on screen?

Porn, psychology, and the racial imagination

Machel Lerone Hunt, PhD, an Atlanta-based psychosexual therapist, doesn’t mince words. “The portrayal of Black men in porn is likely to have a detrimental impact on both the audience and the performer,” he says. “If the viewer can’t distinguish fantasy from reality, they will treat Black men accordingly.” And in the age of parasocial intimacy – in which people form one-sided and un-reciprocated intimate relationships with a media figure or online personality – social media has only made that harder, for everyone involved.

Jason*, a white gay man from London, admits that porn shaped his early understanding of Black men in ways he now finds uncomfortable. “I’ve exclusively dated Black men. I had to confront that porn influenced how I treated partners, socially and sexually. I’m not proud of that. It took age and unlearning.”

Others are still navigating the grey. George*, 31, an Australian in London, describes himself as “predominantly into Black men, but not exclusively,” and confesses that his media diet has blurred the lines between appreciation and fetishisation. “Porn performers are just a few clicks away,” he says. “That accessibility has definitely affected how I connect with people in real life. It’s been emotionally unfulfilling.”

And therein lies the paradox. While Black men may be the most searched on sites like PornHub (“Black” was the top race-related search in 2024’s gay category) this statistical visibility doesn’t translate into lived equality. Offline, respect remains scarce.

“I had to learn not to perform for someone else’s pleasure” – James, a performer, on sex in and out of his profession

James*, 38, is a former US-based performer who knows the aftershocks all too well. “The guys who knew my past wanted me to replicate it in the bedroom. Those who didn’t had assumptions anyway. I had to learn not to perform for someone else’s pleasure. That’s not intimacy.”

Performers, he says, often spend years post-career reclaiming their identity from their persona.

Dr. Hunt agrees: “Black performers may feel empowered in the moment. But over time, the reduction of their identity to a racial stereotype – aggressive, dominant, hypersexual – creates a false sense of agency. They think they’re in control. But it’s often exploitation wearing a different outfit.”

Even behind the camera, racial power dynamics persist. A white, London-based OnlyFans creator who frequently collaborates with Black performers candidly reveals, “My audience likes it. We both make more money. But I don’t want that to be my ‘thing.’ Not in a bad way.” The implication is clear: whiteness wants the spice, just not the label.

The fantasy, the frame, the fallout

Gay porn isn’t immune to the oldest trope in the book: the dangerous allure of the Black male body. Stereotypes persist – “BBC” (Big Black Cock), “thug,” “power top” all pervade and not as relics of a racist past, but as profitable present-day narratives. Some performers embrace these labels as savvy branding. Others see them as psychological quicksand.

The stereotype of a larger penis size in Black men has been subjected to scientific and cultural scrutiny, with inconclusive results. The theme is found in both straight and gay pornography, and many Black men argue that it is a positive stereotype. Andrew Akuruka, Chef and Mental Health Activist, London, says: “If I’m looking for a transactional hook-up, I have used this [stereotype] to my advantage, especially online.” In contrast, others say that it perpetuates unrealistic expectations and, in some cases, even incites animosity through feelings of jealousy.

Cody.xxv, an OnlyFans content creator based in Paris, knows this all too well. He tells me, “I’ve had white men quickly tell me they’d like a gang-bang with me and other Black men, [they assume Black men are all tops], and this has come from porn; this happens a lot on dating apps.”

“We’re not seen as human but rather as someone to fulfil their fantasies” – Cody.xxv, an OnlyFans content creator on his identity in content creation

He adds: “I’ve experienced sudden racism when I’m not interested in someone; we’re not seen as human but rather as someone to fulfil their fantasies. Many white men who have said they’re happy to sleep with me but not be in a relationship, because of what other people will think of them dating a Black guy.”

Critics of porn’s racial politics argue that the industry reinforces real-world hierarchies under the guise of fantasy. Supporters insist sex work is work and should be shielded from sociopolitical burden. But both can be true.

Porn is not a singular culprit, but a potent amplifier of societal issues, in a society still grappling with race, power, and desire, all media formats make a difference.

For some, watching Black men in porn is harmless escapism. For others, particularly those already primed by internalised bias, it becomes confirmation. Blackness is desired, yes. But also dominated. Controlled. Stripped of emotional nuance.

And when Black men internalise these portrayals? It creates a dissonance: we’re watched, yet unseen. Celebrated, but not respected. Fucked, but not loved.

Who owns the narrative?

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether gay porn is problematic. It is. So is most media. A meta-analysis by Malamuth in 2009 found that hundreds of papers from the 1980s to 2008 were fairly consistent in linking high rates of porn viewing with violent ideas and behaviour. But here’s the caveat: not all men respond to porn in the same way.

The more urgent inquiry is: who benefits from the commodification of Black desire? Who’s steering the narrative, and who’s reduced to a clickable fantasy?

In this complex ecosystem of autonomy, exploitation, fantasy, and reality, one thing is clear: Black performers are not monoliths Some are entrepreneurs, reclaiming power on their own terms. Others are navigating the psychological fallout of having their worth measured in stereotypes.

What they all share is the burden of being seen through a lens that rarely reflects the whole picture.

Sex work isn’t the cause of society’s racialised desires; it’s the symptom. Until we confront what we truly consume when we consume the Black body, we’ll keep mistaking fantasy for fact. If the commoditisation of Black bodies in the digital era is feeding the ongoing fetishisation of Black bodies, we all carry a responsibility to treat those around us with respect.

*Names have been changed.