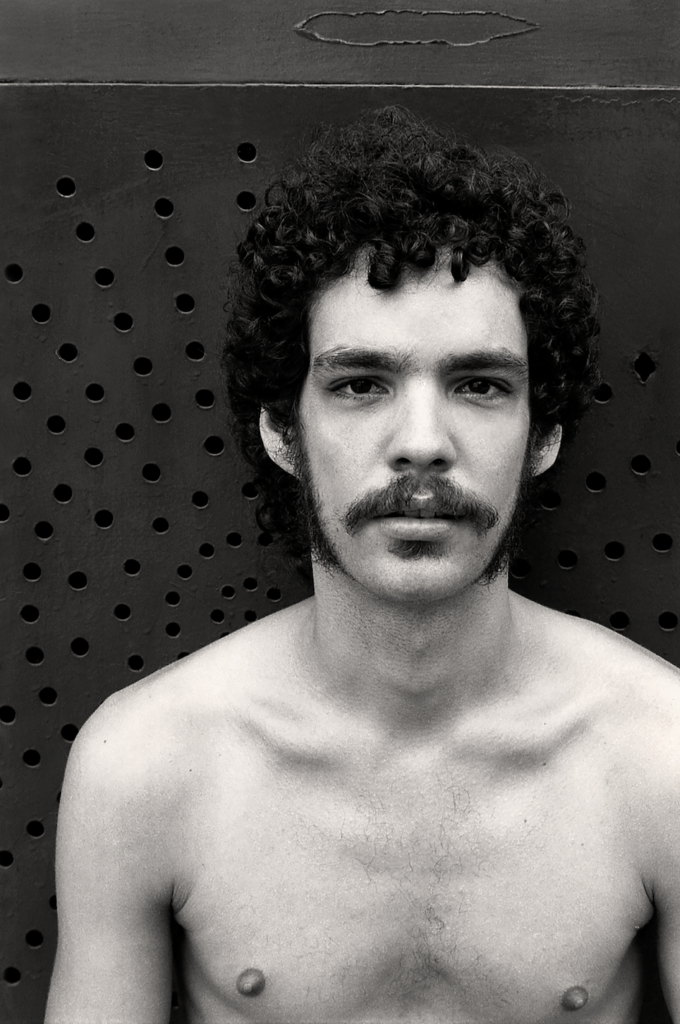

6 pictures by iconic photographer Stanley Stellar that capture male beauty in all its glory

Stanley Stellar took photos of gay men in New York City when the queer scene wasn’t of much interest to other photographers. David McGillivray interviewed him to find out more…

There’s a Facebook group called Vintage Workingmen Beefcake, which has more than 50,000 members. Sometimes the old photos of Marlboro Men and Muscle Beach bodybuilders attract hundreds of views. Scrolling down the posts a few months ago, I discovered a distinctive picture of a bare-chested man with a VPL (visible penis line), making a call from a public phone box. The comments were very appreciative. A lot of people wanted to know more about this photo. Then somebody revealed, “It’s by Stanley Stellar.”

“At a pay phone on the corner of Christopher and Bleecker Streets, NYC” is one of tens of thousands of photos taken by Stellar, an American photographer. They’re mostly of men in New York City, where Stellar was born and still lives. It’s impossible not to wonder what became of the nice-looking man Stellar noticed using a phone booth. This is because Christopher Street is in the heart of New York City’s gay village, and also because the photo was taken in 1981, the year the New York Times first reported on a “Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals”.

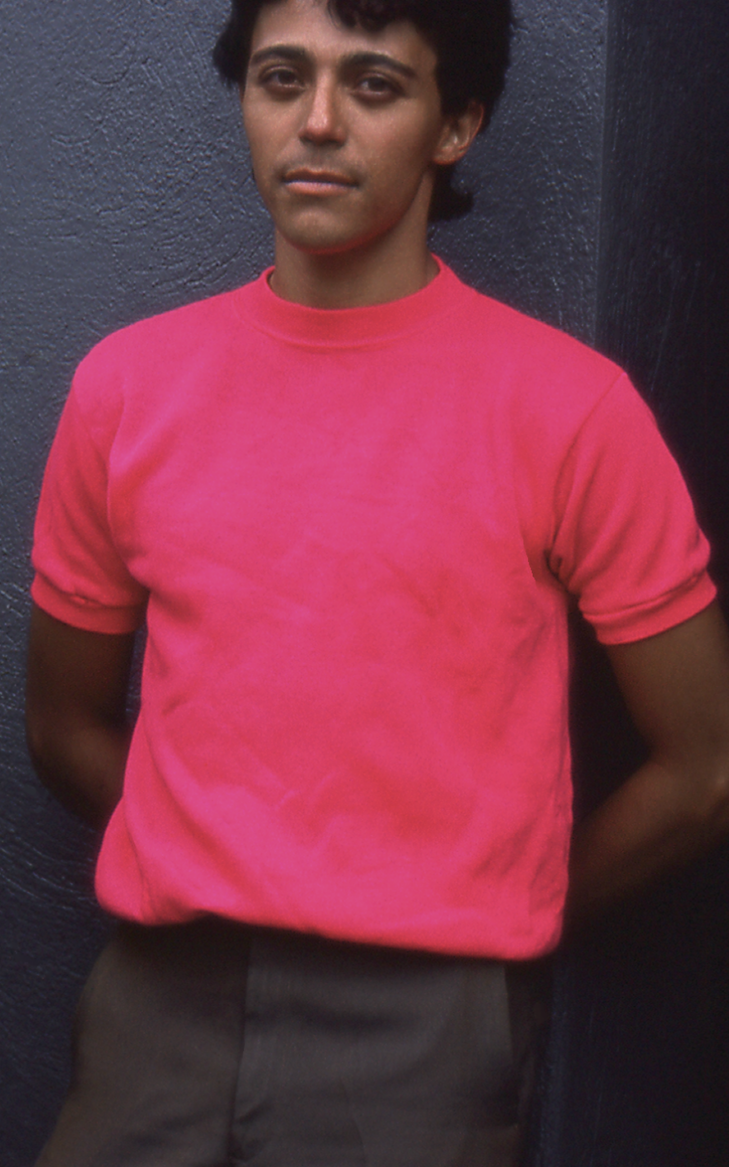

Now aged 76, Stellar is still a photographer. But now everybody is. The Stellar photos that fascinate us today date from the 70s and 80s, when hardly anyone used a good camera to record everyday gay life. “I didn’t think the world needed another gay man to be a fashion photographer,” says Stellar. Instead, he took candid pictures of men cruising or celebrating at Pride. As the times changed, men who had been diagnosed with HIV wanted their photos taken before it was too late.

There’s one particularly symbolic Stellar photo that poignantly bridges two eras of LGBTQ+ history. It’s of a group of young men, one in a Day-Glo shirt, apparently surprised outside a building. The photo was taken in 1979, when the building, at 180 Christopher Street, housed the Cock Ring disco downstairs and a gay hotel upstairs. Since 1986, it’s been Bailey-Holt House, which is now New York City’s oldest residence for people living with Aids.

“It still resonates with me whenever I see that building,” Stellar tells me, before adding, “It was the early 80s. Do I have to tell you? Doctors didn’t want to see gay patients. We didn’t even talk about Aids. We read about it, and people were already starting to get sick, but when I was hanging out with my friends, we could not bring ourselves to talk about the subject…” Later, Stellar knew he had to record the relationships between men who were hiding their HIV-positive status.

Although Stellar becomes emotional when he remembers the worst years of the Aids crisis, he is generally jovial and laughs a lot. He has a dome-like head and a grey beard that varies in length. It was Methuselah-like when he appeared in the 2019 documentary, Stanley Stellar: Here for This Reason, but at the moment it’s neatly trimmed.

He remembers becoming captivated by photographs during his childhood. “My main activity when other kids would be out playing,” he reveals, “was to sit on the floor of my grandmother’s room in Montreal and look at her magazines. For me, magazines became a way to find out about life. Photographs in magazines became my friends.”

He has often claimed that as a child he had no real friends. “Absolutely,” he confirms. “Even walking to school, I noticed that the boys taking the same route seemed to not see me, [or] ignore me, walk by me. And I’d think, ‘Hey, aren’t I just like them? How come we’re not friends?’”

From his mature viewpoint, today Stellar realises he would have had little in common with those boys, whose behaviour betrayed their ignorance. “Now I think it’s great,” he states, before lamenting the lack of intelligence he still observes in people today. “It grieves me to see today’s young gay men on Instagram looking so clueless.”

Stellar was about 12 when he asked a stranger in a local store to reach up to the top shelf for a copy of One, a magazine that expounded on “the homosexual viewpoint”. It was first published in 1953 by the pioneer homophile group the Mattachine Society.

“Ever since childhood,” he explains, “I was aware I was a homosexual and yet, at the same time, there was no way I could ask anybody, ‘What’s that like? Am I going to be happy?’ Part of my original impetus [as a photographer] was to find out who gay men are. At this point in my life, I realise that I saw little bits of myself constantly in almost everybody I ever stopped and photographed. It’s that humanity that I recognise.”

What did he learn about photography at New York’s Parsons School of Design in the 60s that he couldn’t have taught himself?

“Composition and design,” he replies, quickly. “It was a great opportunity, a wonderful time for me.”

Afterwards, during the 70s, Stellar worked as an editorial art director designing magazines and books. As he saw and commissioned the work of photographers from all over the world, he couldn’t detect whether a portfolio of women’s fashions had been produced by a gay or a straight man. It was this that spurred him in the mid-70s to develop his own style of photography, to take unequivocally “gay” pictures of men, ones that reflected the world he knew.

I put it to Stellar that photographer Peter Hujar (1934-1987) must have been an influence on his work. Hujar used all kinds of subjects, but he’s perhaps best-known today for capturing many aspects of queer society in New York City. He and Stellar frequented the same cruising grounds and latterly they were friends. Stellar even took a picture of him getting a blow job — we’ll return to that later.

“He was a big influence but not my major one,” Stellar corrects me. He claims that he was more connected to Richard Avedon and Bruce Davidson, whose work he admired in Look and Life magazines.

Expanding on the theme, I open a can of worms when I point out that, despite the fact that they both photographed white models with black partners, as well as leather men and flowers, Stellar doesn’t cite Robert Mapplethorpe as an inspiration.

“I don’t want to talk about him,” Stellar snaps. “He doesn’t interest me. I don’t respect his work. I respect that he was a pioneer but when I look at his work… I don’t want to talk about him. I’m sorry.” But then it seems he can’t stop.

“I don’t relate to his work,” he continues. “His work is soulless and mine is all about soul. He had this great karma — right place, right time. He had a blessed life and he revolutionised our ability to look at male imagery. He could photograph $150 lilies very well. But when you photograph something beautiful, it’s not hard to take a beautiful photograph. OK? That’s all I’m gonna say about him.” In fact, he says a lot more, ending with, “He was never an influence on me. Get the message? Right, not an influence.”

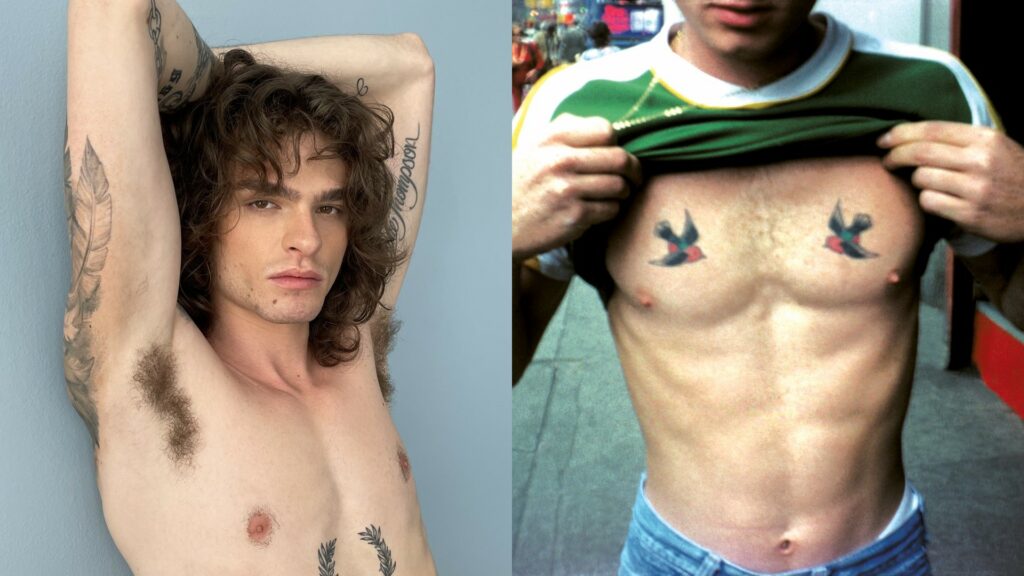

Stellar is much happier to speak about how he began taking photos of men in the street. He learned that he appeared less predatory when he showed an interest in tattoos, often eagles, on men’s arms. In 70s New York City, tattooing was illegal and so it was a talking point. Stellar recounts the story of one of his most famous photos, “I Got Birds Too, NYC” (1976).

“I see this guy and he’s young, attractive, a redhead, nice body, walking with his friend. I walked up to him and he let me photograph his arm and, as I was walking away, he said, ‘I got birds, too!’ and I didn’t know what he was talking about. He was already lifting up his T-shirt, showing me an image of birds over his gorgeous pink nipples against his white skin with freckles. I just went ‘click!’ and I took the picture, one frame. I smiled and thanked him and walked away and, in that moment, I knew I had just made a homo-erotic image that no one had ever made before.

“There was this world of hidden tattoos. They became even more erotic when they were hidden. A hidden tattoo would eroticise that area on their body. I stopped being interested in all the eagles. [Those were] like a signpost saying there could be more here. It took me a few years to realise I was interested in all men, not just tattooed men.”

It’s not clear from his work how much is posed and how much is grabbed, I say. Stellar is vague. “Grabbed?” he repeats. “I understand the use of that word but for me it’s more like I’m standing here in the middle of my brothers and sisters and I have every right to stand here and look at them because they’re looking at me. So yes, I took their pictures, you could say grabbed, but mostly it’s just me seeing who’s there and what looks good to me.” When pressed, he admits that maybe 50 per cent are grabbed.

Has anyone ever objected to being photographed? “Hardly ever. I don’t think it ever happened,” he claims. “But I have to tell you this, David: I had a job at the Leslie-Lohman Museum. I would go to their show openings and photograph the guests. Some weird person would walk across the room to tell me that they absolutely did not want me to photograph them. And it would be somebody I wasn’t even looking at or could care less about!”

The abandoned piers and warehouses in Manhattan’s West Village provided Stellar with one of his most fertile hunting grounds: “When New York City stopped being a hub for steamships and freighters, those piers just sat deserted, idle, disintegrating in the weather. I noticed that men were sometimes walking in the direction of the piers, but there was a big, wooden fence, 8 feet high, that surrounded three or four piers. I just walked that way one day, thinking, ‘Where’s that guy going?’ We knew how to recognise each other very clearly. By that time everybody was wearing a hanky flapping out of his back pocket. [The “hanky code” communicated specific sexual interests between gay men.] There on the side of the fence was a piece of wood that moved.” Stellar lifted it and entered a secret world. “Why not? I felt so comfortable. It was my neighbourhood so I wasn’t nervous.”

One photo Stellar took on the piers is of Peter Hujar (“Peter gets his dick sucked,” 1981). Is the drawing on the wall by Keith Haring (1958-1990)? I ask. “Of course,” replies Stellar, who photographed the pop artist’s work all over New York City.

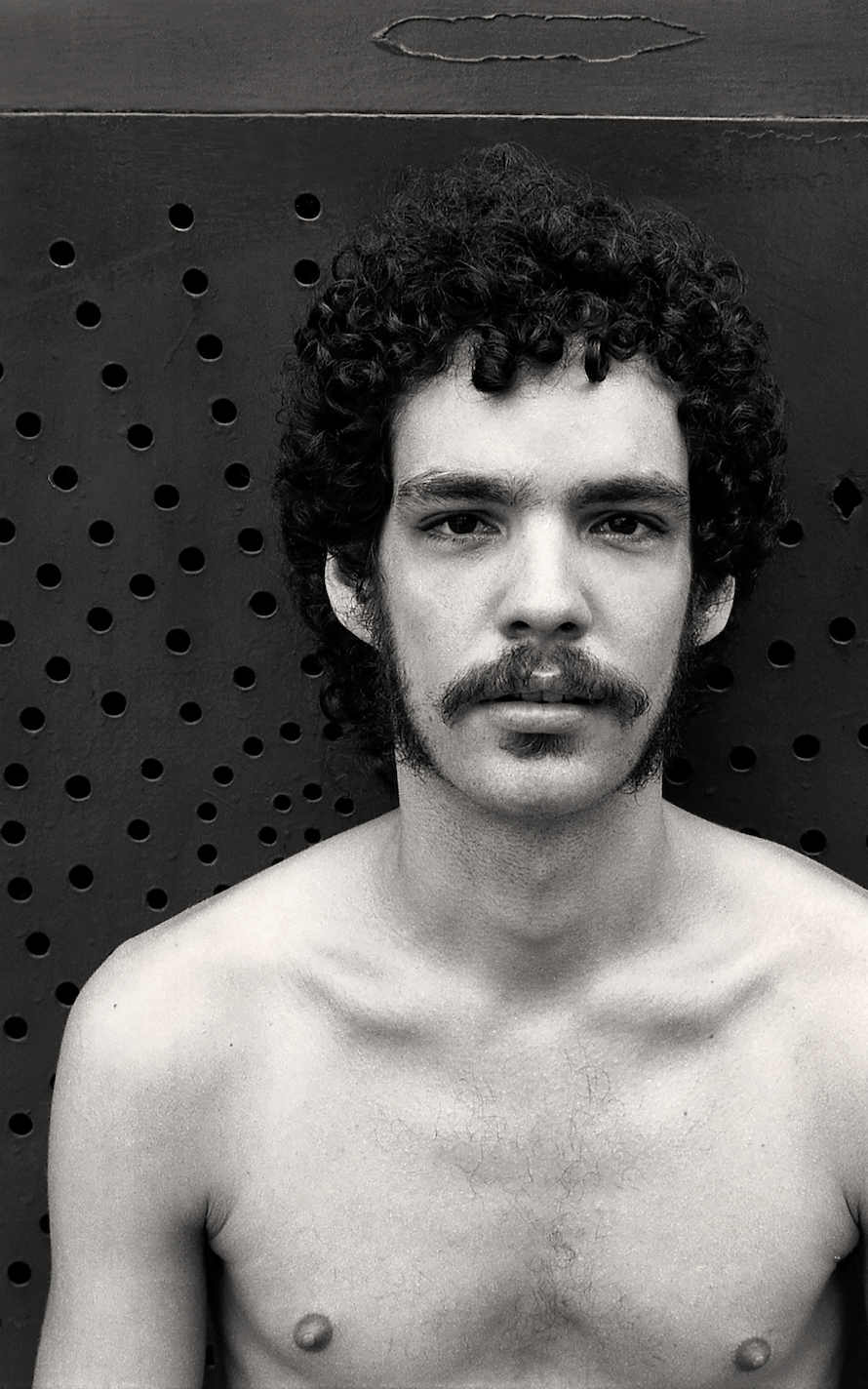

When Stellar began photographing men in his studio, he produced some of his most beautiful studies: men in love, others who wanted to make a kind of statement. They were usually nude. Stellar advertised in the gay press for models.

“The advert would say ‘Male models wanted. Nude dudes.’ I made that up. Maybe I had a post office box. I mean, I wasn’t going to put my phone number there. I’m sure you’ll like this: I still have a lot of those handwritten application letters that people wrote me back then. With a picture. They’re gorgeous artefacts. It was amazing to me that men would take the one little nude picture they had of themselves, put it in an envelope and send it to someone they didn’t even know.”

I tell Stellar I’m going to be blunt. I ask him if he had sex with his models. To my relief, he doesn’t mind this question at all. “Of course. Yes, what the hell?” he laughs. “But not all of them, you know? The ones where there was chemistry, sure. Very often in those days, gay men, bisexual men, married men wanted to see how good they looked, so they had to come to someone like me with a camera who had some awareness and know-how. But no matter what their sexuality was they would have erect penises the minute I said, ‘Take your underwear off.’ They’d drip on the floor. They were enjoying having this erotic experience that was unique.”

None of the models was a pro. Stellar has never been interested in them. “That’s not what my work is about,” he insists. “It’s about humanity, it’s about their inner light, it’s about giving people this opportunity to play this visual game with me and let themselves be vulnerable and beautiful.”

It’s therefore hard to find recognisable faces in Stellar’s gallery, but there are one or two, notably porn star Al Parker (1952-1992). “He was already a huge legend,” Stellar confirms. “He and a friend were walking down Christopher Street one day [in 1987] but on the side that most people did not walk on. I saw who was across the street and I wasn’t gonna miss the opportunity. I approached Al Parker in the same way I approached everybody else. My way of approaching people was to be totally honest, upfront and real and say who I was and why I wanted to photograph [him], what it meant to me. I wanted that reality back in my photos.”

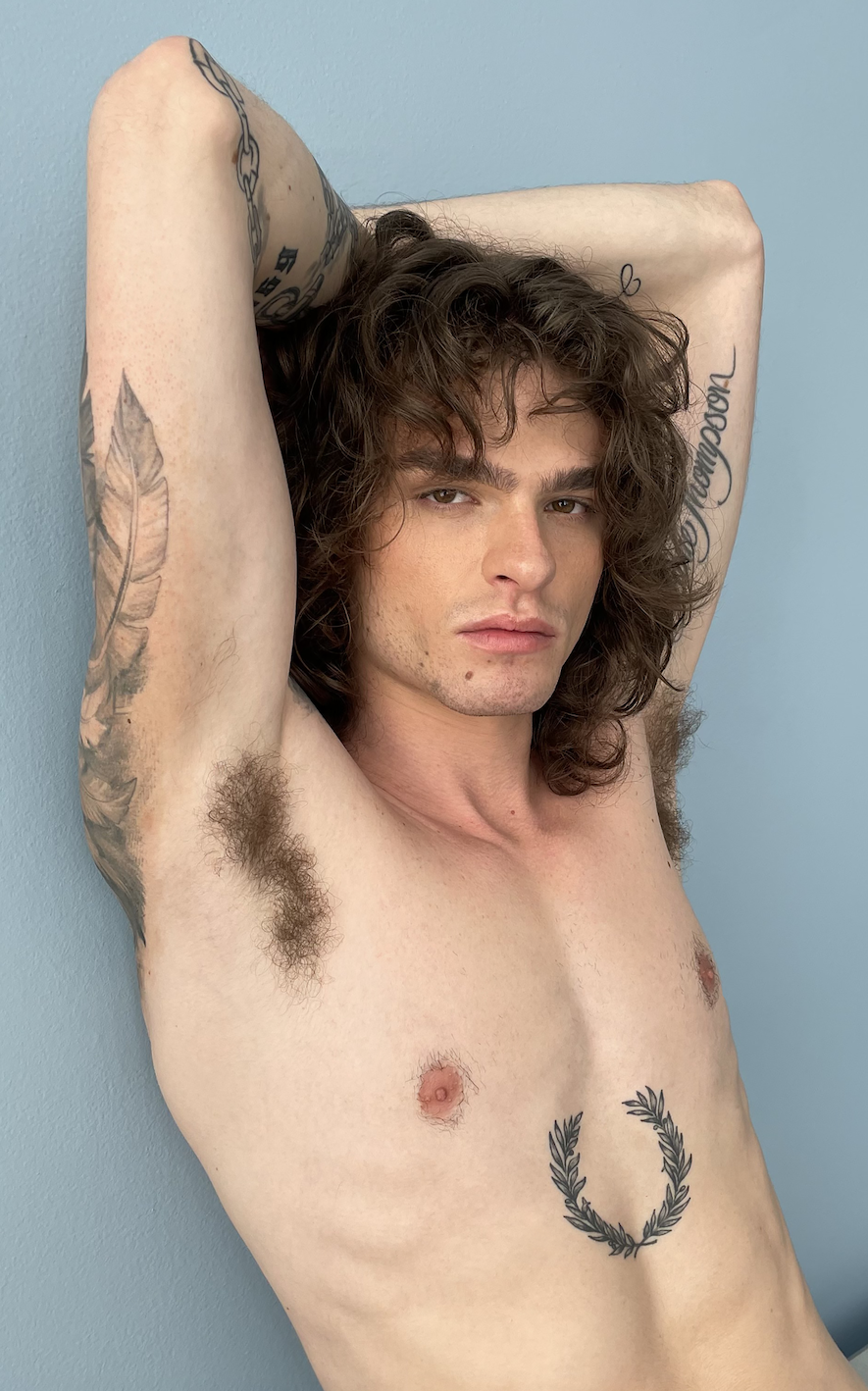

Most of Stanley Stellar’s work has a deceptive simplicity, a blend of composition and matter-of-factness that’s hard to achieve. This is the result of the amiable photographer/sitter relationship of which he’s so proud. His earlier work, done when he was effectively a photo-journalist, and the more light-hearted shots he takes today have a continuity. One recurring theme is armpits.

“I’m a fetishist,” he responds. “I’m not uptight about my enjoyment of queer fetishism. I like how armpits look, how they smell. But I like all kinds of body parts, absolutely. And more than that, David, if you knew me, I’d show you some interesting things. So much of my work has never been seen!”

I assert that he puts some of his models into what look like difficult poses. “I don’t think they’re difficult,” he argues. I try to demonstrate what I mean: balancing acts on the sides of sofas and chairs. “I’m interested in the physical poetry I can see in their bodies,” he explains. “That’s what that’s about. When they give me something like that then I know that what I’m doing with them is real. I don’t want to make clichés, David! I hope when you look at my work you don’t see clichés.”

I go on to guess that generally he doesn’t like his models to smile.

“Absolutely,” he agrees. “From my experience, people who learn to say ‘Cheeeeese’ aren’t giving you anything real. Simple. I want some truth, I want some reality, I don’t want a pose. Do you know my photograph of Marsha P. Johnson?”

I tell him that I have seen his portrait of the Gay Liberation pioneer and know the story behind it. Stellar came across his friend one day in 1987 when the light was good and asked if he could take a photo. Johnson switched on her “photo smile” and Stellar said, “No, I want you to look at me like I’m looking at you.” Johnson died — possibly a victim of murder — in 1992.

I ask if Stellar wonders what became of the men he photographed over a period of about 50 years? “It’s a question that people leave all the time on Instagram,” he admits. “I think, ‘Are they serious?’ What do they think happened to any of us? What, what? Tell me.” I get the impression he’s implying that many of his models won’t have survived the Aids pandemic.

“Sometimes I look on Facebook for someone that I was particularly fond of,” he elaborates. “I’d say 60 per cent aren’t there. They’ve disappeared. Forty per cent are there but they’re drastically different. The guys I thought were the biggest fist-bottom pigs are teaching piano in Connecticut. In order to survive they had to change.”

The guy at the pay phone: where is he now? “How would I know? I have no idea,” Stellar says. A pause and then he adds, “It’s interesting that some of my images have been evocative for you, David.”

This feature first appeared in issue 356 of Attitude magazine.