Opinion: We need to talk about racism in the LGBT community

Attitude Editor-in-Chief Cliff Joannou addresses the fall-out from the Manchester Pride flag furore ahead of Attitude and Student Pride's 'Pride Not Prejudice' panel this Saturday (23 February).

By Will Stroude

Attitude and National Student Pride‘s ‘Pride Not Prejudice’ panel will take place on Saturday 23 February at London’s University of Westminster Marylebone campus.

White people don’t like to talk about racism. It’s uncomfortable to address, because it reminds us about our privilege. A white person’s privilege persists despite their class, social status or standard of education.

For example, they are likely to get a job over a black person applying for the same position, even if they have equal qualifications and experience. That is how white privilege – and institutional racism – works.

But, as Lady Phyll from UK Black Pride stated earlier this week at a panel discussion at the Omnibus Theatre, on art and activism: “Privilege is not a problem if you are using your privilege to elevate other voices.”

I’ve had an interesting relationship with my own privilege – my identity shifts according to the person categorising me. Growing up in predominately working class Thornton Heath in South London, my neighbours and school friends were largely white and British. We were the Greek Cypriots next door that (we were told by our friendly white neighbours) smashed plates at weddings.

My mum and dad, loving and good-hearted as they were in most aspects of their parental duties, still harboured racial prejudice despite themselves being the subject of stereotyping because of their ethnicity. My cousins would have never brought a black or brown boyfriend/girlfriend home. That would have been unthinkable. Love was something only to be shared within our own culture.

I was raised in an environment that accepted people of different colours – as long as they weren’t too close to home. I had to unlearn racist attitudes that my culture taught me, that proliferated in wider society and was endorsed in the media we digested.

I was foreign and ethnic when around white British people, and squarely white when I was around my black and Asian friends. But I can’t for a second fathom what it is to experience the racism that a person of colour does.

Case in point? The furore when Manchester Pride added the black and brown stripes to acknowledge the under-represented Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) people to the rainbow flag exposed a sinister undercurrent of racism.

Fuelled by a lack of consideration about the message, LGBT+ people (mostly gay white men when you scroll through the comments) were angry that their precious rainbow flag had been tampered with, even though they were ignorant of the flag’s long history.

So, let’s look at its history.

In 1978, Gilbert Baker was encouraged by filmmaker Artie Bressan Jr to create a flag that would become the symbol for “the dawn of a new gay consciousness and freedom.” In his research, Gilbert looked at how the flags of countries such as the USA and France owed their beginnings to rebellion or revolution.

“As a community, both local and international, gay people were in the midst of an upheaval, a battle for equal rights, a shift in status where we were demanding power, taking it,” he says in his memoir. “This was our new revolution: a tribal, individualistic and collective vision.”

Gilbert’s first rainbow flag was composed of eight stripes, symbolising sex, life, healing, sunlight, nature, magic, serenity and spirit, and echoed the peace movement’s flag, with its five horizontal stripes: red, white, brown, yellow and black. But it could easily have taken its cues from the Judy Garland classic ‘Somewhere Over The Rainbow’. Perhaps it was a bit of both.

It was adopted almost immediately as a universal symbol of our LGBT+ community, replacing the pink triangle used by Hitler to mark gay men in the concentration camps.

The flag was soon modified to seven stripes, before eventually being reduced to six in 1979 for the practical reason that it could hang vertically in two halves, one on each side of Market Street, San Francisco. Gilbert referred to this as the “commercial” version, acknowledging that it was as much a thing to be consumed as it was a symbol for our collective identity.

As such, Gilbert refused to trademark his creation. “It was his gift to the world,” says activist Cleve Jones.

The flag represented our community’s evolution as we took the first steps out of the shadows of political and social oppression and into the sunlight. It is a symbol that has been adapted since the day it was conceived — and because of its creator’s decision, owned by nobody and everybody.

Rainbow Pride flag creator Gilbert Baker

To commemorate the flag’s 39th anniversary, Gilbert, who died in 2017, added lavender to the eight original colours to represent diversity. Political and social progress had made the lives of many in the LGBT+ community better but Gilbert understood the challenges that marginalised members of our community continued to live with.

Uproar ensued when Manchester Pride announced in January that it was adopting a version of the flag used by the city of Philadelphia in 2017, featuring a black and brown stripe to highlight issues faced by BAME members of the community.

I am a little baffled by some of these reactions. Adding those stripes takes nothing away from my (rather privileged) life. Was there similar resentment when a black stripe was added in the 1980s to represent those who suffered during the Aids epidemic?

Or in 2018 when a version of the rainbow flag featuring rips in two of the six stripes was used by Olly Alexander from Years & Years in a campaign to highlight how one third of LGBT+ young people have attempted suicide.

The standard rainbow flag still exists in its timeless and commercially popular six-stripe form. It hasn’t vanished — and it’s unlikely it ever will.

But if a campaigning community group such as Manchester Pride feels that adding two extra stripes sends a signal to even one isolated person that they are included no matter the colour of their skin, then all power to it. I’m sure Gilbert would agree. And I’m also sure he would be horrified to see the racism that filled social media when the flag was revealed.

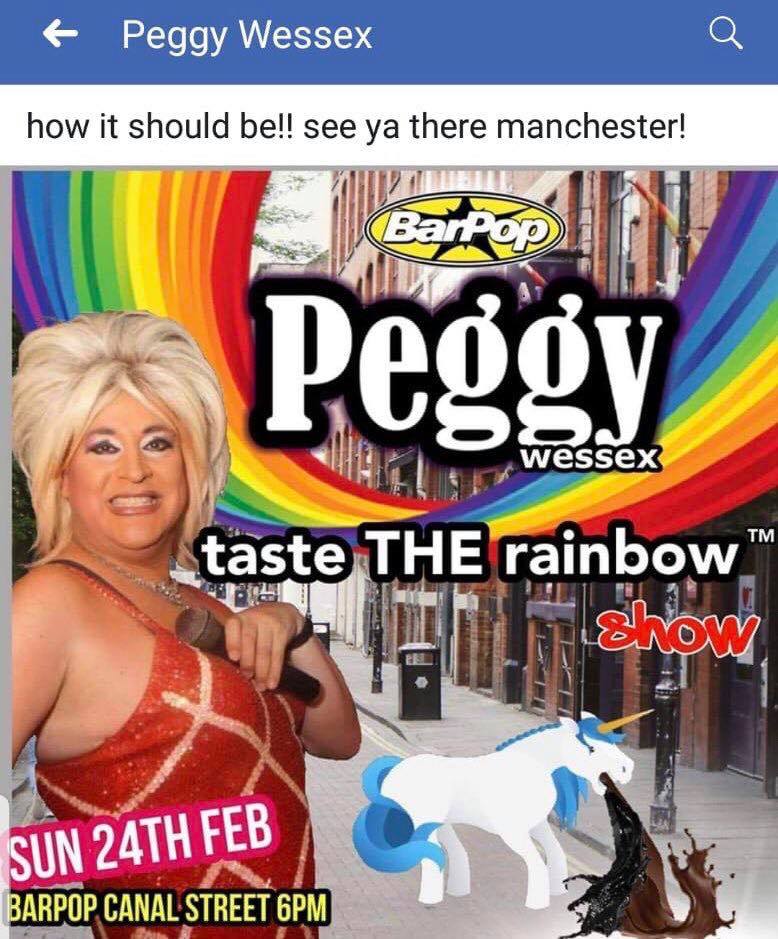

It’s disappointing that Manchester-based drag queen Peggy Wessex continues to be blind to the varied history of the rainbow flag she is ardently defending when she shared an image of a unicorn vomiting the black and brown stripes on social media. It was a vile gesture on her part and anathema to the understanding community we should be striving to become.

Racist action is not just about the active disparaging or alienating of people of a different skin colour through aggressive words or actions. It’s not just the use of derogatory language. It is also the passive ways that we allow racial oppression to continue unchallenged.

It’s not easy for white people to talk about racism because it means we have to be honest about our privilege, and recognise what we are or are not doing to make the world a fairer and more equal place. This is why we need to talk about racism. We need to challenge it in others, and yes even within ourselves and our community, wherever it manifests because that’s the only way we as a community can grow stronger.

On Saturday 23 February I will be joined at Student Pride by the BBC’s first LGBT correspondent Ben Hunte, activist and model Munroe Bergdorf, Moud Goba from UK Black Pride, Shahmir Sanni and model Reece King for ‘Pride not Prejudice’, a panel discussion on the issues faced by BAME people in LGBT+ community.

Come and join the us. Bring a flag and wave it proudly — whatever your choice of flag looks like. All are welcome.

Follow Cliff on Twitter @CliffJoannou.

Attitude and National Student Pride’s ‘Pride Not Prejudice’ panel will take place on Saturday 23 February at London’s University of Westminster Marylebone campus.

For your free ticket to Saturday’s daytime festival click here.