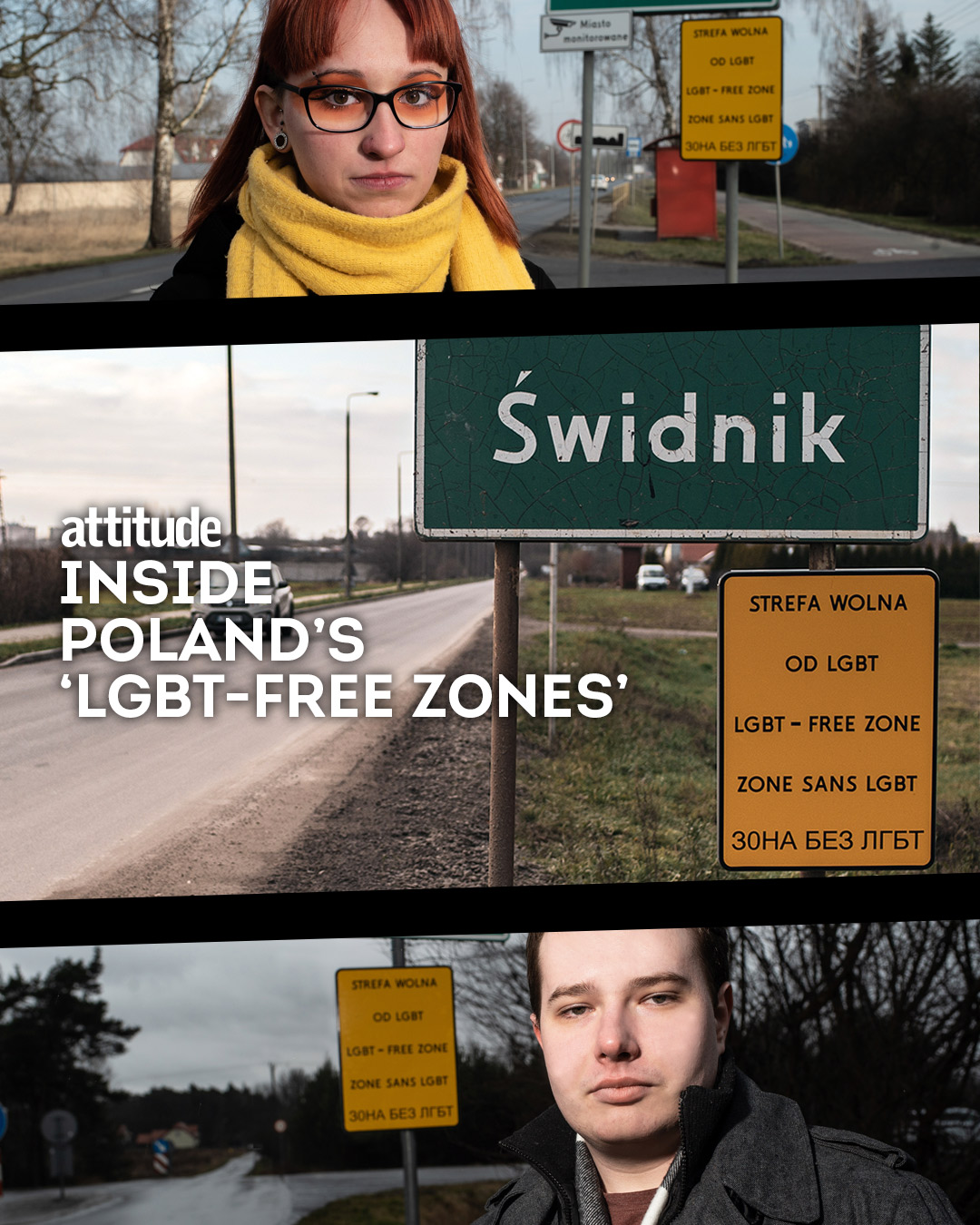

Inside Poland’s ‘LGBT-free zones’: ‘Violence on a larger scale doesn’t seem too far off’

Poland’s ‘LGBT-free zones’ are a grim reminder that, even in Europe, the fight for human rights is far from over. In a special series, we speak to three queer people living inside them.

By Will Stroude

The full edition of this article appears in the Attitude Summer issue, out now to download and to order globally.

Words: Ruben Wissing

They have already been around for a year now, the so-called ‘LGBT-free zones’ in Poland. Some 90 municipalities, primarily in south-eastern Poland, have officially declared war on what they deem ‘gay propaganda’.

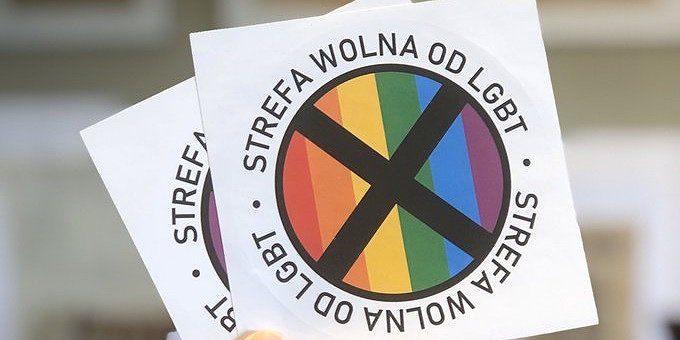

A far-right Polish news magazine has been distributing ‘LGBT-free zone’ stickers and thousands of hooligans have been attacking Pride demonstrators. Although the European Union condemns what is taking place within its territory, that doesn’t seem to be having much of an effect — the conservative government feels that Brussels should keep its nose firmly out of Poland’s business.

In February 2019, the municipality of Warsaw created a manifesto aimed at achieving equal rights for the queer community, and providing better information on gender and sexual orientation. But what they achieved was the absolute opposite: Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the ruling conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, labelled the manifesto both anti-Polish and a threat to Christian family values, stating that LGBTs* should keep their hands off children, with their “masturbation lessons”.

His statements were met with resounding support from the electorate. He had clearly found a scapegoat for his campaign for the European elections, which he overwhelmingly won. After that, the Archbishop of Kraków – a man with considerable power – took things up a notch by talking about a “rainbow plague” that would infest Poland. Then, the far-right news magazine Gazeta Polska started their ‘LGBT-free zone’ sticker campaign.

As a final, sour cherry on the cake, local authorities in Lublin created an antimanifesto, the first resolution to make a Polish municipality ‘LGBT-free’. At the time of writing, almost one-third of Poland has followed this example. We find out what it’s like to be LGBT and living in one of these zones.

JAKUB, 38

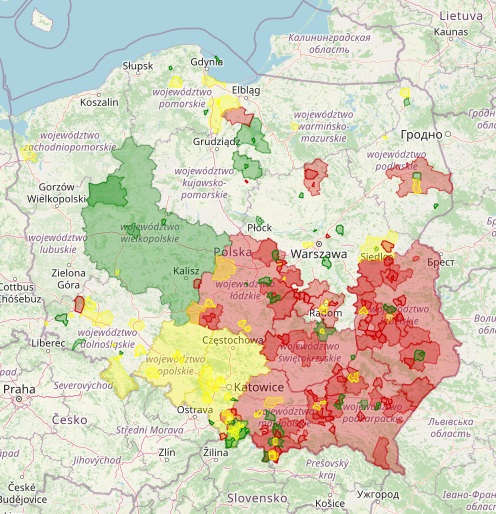

Jakub lives in the south-eastern city of Rzeszów. A gay activists, he works in IT in aviation. Together with two other activists, he has created the ‘Atlas of Hate’, an interactive map of Poland that delineates the ‘anti-gay’ zones.

How did the ‘LGBT-free zones’ come about?

Unfortunately, this is not a new phenomenon, except that the ruling PiS party incorporated discrimination into official documents in 2019. On the basis of a declaration by the city of Lublin in eastern Poland, around 90 municipalities accepted resolutions against what they term “LGBT ideology”. They claim that we are endangering the 1000-year-old tradition of baptism for children.

We might not be personae non gratae in these zones, but it is certainly a way to shut us up. For instance, grants and subsidies are being withheld, equality marches are now outlawed and progressive nongovernmental organisations are no longer allowed to provide anti-discrimination lessons at schools. This campaign was primarily conceived by the ultra-conservative organisation Ordo Iuris and the Catholic Church, and the government is only too happy to implement it.

Are these resolutions compulsory?

No. Although there is seldom any deviationfrom them, whether or not that can be put down to fear or conviction. For example, if a female student wants to organise Rainbow Friday – a campaign for the acceptance of LGBTs in Poland – the request now has to pass all kinds of boards beforehand, and then, naturally, there’ll be someone who takes offence, who says that the female student isn’t dressed chastely enough, and so the permission gets denied.

When it comes to projects and organisations that are seen as ‘undermining the values of family and marriage’, things are made so difficult financially and bureaucratically that it’s better for them just to terminate whatever projects and proposals they might have – either that or the media is brought into it. Schools that stand up for antidiscrimination lessons can also look forward to a visit from Ordo Iuris’ lawyers.

Is it different for you to walk the streets of Rzeszów now that the city is ‘LGBT-free’?

I’m more watchful now because I organise equality marches, and can therefore be considered a target. I also get the feeling that I’m being watched, and that my already restricted comfort zone is getting smaller and smaller, but as long as the nationalistic state broadcaster publishes my name without a photo next to it, I feel reasonably safe walking down the street. In my job, I often deal with calculations of probability, which means that I can put it in perspective to some degree.

Poland’s ‘LGBT-free zones’ as depicted in Jakub’s ‘Atlas of Hate’

You and some friends have drawn up the Atlas of Hate. What does that entail?

The Atlas is a schematic depiction and database of all the anti-LGBT resolutions in Poland, including official documents. In order to help shed a bit more light on the matter, we made a map to accompany it, which makes it clear just how complex and widespread the phenomenon is. Last November, it was also used during a debate in the European Parliament. The map seemed to really hit the mark, and received an incredible amount of media attention, which led in part to the EU rejecting the resolutions.

How have the authorities reacted to your criticism?

They get furious if we point out that they are discriminatory. They feel that they are supposedly not acting against a specific group of people, but merely against an ideology. But that ideology is our very existence, in this case. We’re only just beginning to notice how much anger our project has actually caused. We are being taken to court right now by Ordo Iuris, as we are allegedly giving municipalities a bad name, and accusing them of homophobia. Well, I wonder where we could have got that idea from? What they are looking to do is to make us completely invisible.

Is it safe for you right now?

I try not to think about it too much, but if anything were to happen to me, then I don’t think that the police and prosecutors would do much to assist me. If I report death threats to the police, for instance, I am completely ignored – or I am told that they couldn’t find the culprits, even after I have provided them with the personal details of the perpetrators. This seems to be acceptable, due to the fact that hate crimes on the basis of sexual orientation are not specifically mentioned in our penal code. A year ago, I reported some people in their twenties who had publicly incited violence to the police: they wanted to fire airsoft guns at an equality march that I had organised with a few other people. The police reaction was, “You can’t spill anyone’s guts with weapons like that,” so in other words: “What are you getting worked up about?”.

How do you view the future?

I can imagine that this could get a whole lot worse. It started out with them tolerating hate speech; now we are already talking symbolic exclusion and minor punishment for crimes against minorities – our judges implement whatever the government requires them to. Violence on a larger scale against LGBTs doesn’t seem too far off, and this is being fuelled by Nazi-type propaganda on TVP, the national TV network, which is run by the government. A few days ago, a couple from Lublin received no more than a year’s imprisonment for planning a terrorist attack on the equality march in the city. The public prosecutor’s office only convicted them for making explosives, but the bomb they assembled could have taken many lives.

What do you think should happen now?

We are looking for international organisations to support us, especially now we are being made to appear in courts of law as traitors. Many Polish cities have twin cities in Western Europe; in a number of cases, those ties are now being put on hold or even broken. That seems like a good development, but there are many young queers in the Polish countryside, for instance, who are given the opportunity to go abroad temporarily because of international cooperation – an experience that is essential for many of them to get a more positive outlook on life. I hope that the Dutch authorities and twin towns and cities take this into account and keep advocating dialogue and the realisation of small-scale workshops.

Wouldn’t you like to go abroad?

The state has now officially made me a second-class citizen, but I’m not going anywhere; that would be playing into their hands, it’s exactly what they’d want. I want to stay here and speak up against injustice and the violation of fundamental human rights.

Read more about life inside Poland’s ‘LGBT-free’ zones in the Attitude Summer issue, out now to download and to order globally.