Beyond gender: Why non-binary identities and pronouns are nothing new

Often dismissed as a New Age phenomenon, non-binary language can be traced through history.

By Will Stroude

This article first appeared in Attitude issue 321, May 2020

Words: Otamere Guobadia

Outside our queer windows, an identity war is raging. At the centre of this prolonged battle are gender pronouns.

From courtrooms to classrooms, and social media bios to fashion runways, gender pronouns such as ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘they’ (and other coined, less pervasive ones) dominate the discourse around gender and just how fluid a person’s identity can be.

To paraphrase Shakespeare, who used the singular “them” in Hamlet, “What’s in a pronoun?”

At the end of 2019, the Merriam-Webster dictionary made headlines when it announced that the pronoun “they” was its word of the year. And a few months before that, Sam Smith, one of the world’s most successful pop stars, with 20 million album sales worldwide — and counting — came out as non-binary, making them unarguably the most high-profile individual to do so.

Sam asked fans to address them with the they/them pronouns, stating that, “After a lifetime of being at war with my gender, I’ve decided to embrace myself for who I am, inside and out.”

For many of us, the proliferation of the singular “they” as an alternative to the binary “he” and “she” helps to close the gap between language and feeling. More and more, we are seeing iterations of pronoun combinations, such as “she/they” or “he/they”, which eschew a fixed, enduring pronoun.

Instead, we are seeing people disregard this very notion of fixedness, choosing pronoun configurations that reflect their current gender (or genderless) expression, and trends that more broadly reflect the mercurial, spectral nature of gender.

For many within our community, these events are a welcome evolution of not just language, but of conversations around gender, queerness and transness. It’s a development that will allow us to breathe more easily, giving us more bandwidth and language for our experiences, and allow the words we use in our everyday to wrap themselves more tightly and comfortably around our limbs and bodies in a more honest, kinder expression of self.

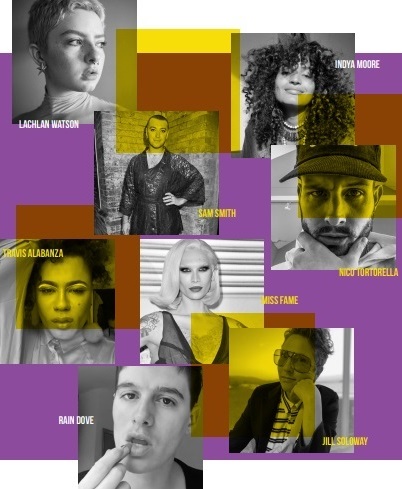

Non-binary stars from Sam Smith to Indya Moore are increasing awareness of gender diversity

Sam’s request that people address them using they/them was a bold move that has been met as much with overwhelming support and empathy as it has with outrage, backlash and pettiness from commentators both anonymous and high profile. For many bigoted people, Sam and other non-binary people’s attempts to assert the singular ‘they’ as their pronoun is a New Age, snowflake invention.

To these “defenders” of “traditional” thinking, the preference or assertion of any pronoun other than he or she — or indeed any attempt to transcend or change the pronouns one is assigned at birth — is an impossibility. Those who do so are, they claim, attempting to co-opt “proper” and “correct” language, and to pervert the course of nature with an attempt to trap everyone in their collective gender-scrambled ether. Their formula is simple: pronoun = gender = genitalia. They declare these things as immutable truths.

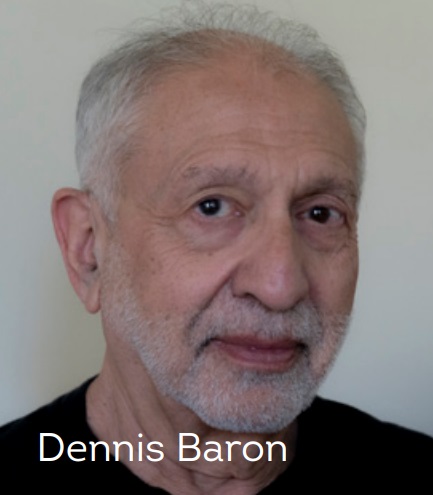

Linguist Dennis Baron disagrees with this rigid thinking. His new book, What’s Your Pronoun? Beyond He and She is a meticulous, consummate dissection of the pronoun wars in which he outlines how the conversations and arguments being made against flexibility (and pronoun innovations) are not new ones, despite a seemingly 21st-century social-justice framing.

“Some years ago, I came upon — quite by accident — some of the coined pronouns in the 19th century,” Baron says, calling me from his home in Illinois, USA. “I was researching people who try to reform language and make changes to improve things, or [at least] they think they’re improving things. I began tracking them down and collecting them.

“I was able to trace the coined pronouns back to 1841, and I was quite surprised to find not just one or two, but eventually several hundred ‘coined pronouns’ — pronouns created by daring individuals to fill perceived gaps in our lexicon.”

When Baron analysed his research, he came to a realisation that, historically, gender is just part of the pronoun discussion. “It became quite obvious that what has been sparking the current discussion of pronouns over the past 15 years has been gender, and non-binary gender, in particular. But the political aspects of pronouns, particularly [the way they interface] with gender reference, goes back well into the 19th century and even into the 18th century.”

Baron thought that he could make a timely and meaningful contribution to the current debate “by plugging in some of the history”. For instance, although modern English uses only four pronouns or addressing a person or persons — such as you, your, yourself, and yours — the English of Shakespeare’s time used 10pronouns: thou, thee, thy, thyself, thine, ye, you, your, yourself and yours.

Baron’s work provides a well-researched and accessible antidote to the cruel stream of invective directed at non-binary people who attempt to adopt they/them pronouns. One of the most common assertions is that ‘they’ is designated plural, and that applying it to a single individual violates the rules of good grammar, thus ushering in a lawless, apocalyptic world full of gender-neutral babies and compulsory skirts for cis-men. This is, of course, pearl-clutching nonsense.

“They’re looking for an excuse,” says Baron. “They throw up the grammar as an excuse to deny rights [and] inclusion. The language becomes a stand-in for discriminatory. It’s easier to say to someone, ‘Oh, you’re a great person, but the grammar is all wrong’. It’s a proxy battle… [it’s made to seem] like it’s less of a personal or group attack and more a case of ‘well, you know, we can all agree that correctness is important’, which is bullshit.

“The idea of [grammatical] correctness itself is a political move to put people in their place, see who’s a member of the club and who is to be excluded… who’s got [received pronunciation] and who doesn’t. It’s part of that general inclusion/exclusion language.”

None of this is new. Baron’s research highlights the parallels between today’s transphobes insisting upon strict boundaries of gender and pronoun usage, and yesteryear’s bigots who once insisted that although the use of ‘he’ in legislation and constitutions excluded women from voting and running for political office, it could be used to include them when it came to legal penalties.

“It seems like pronouns are little words, we tend to think we don’t pay much attention to them, but in fact we do, and the idea that pronouns are some kind of indicator of rights and status goes way back,” Baron says.

Throughout history, when faced with calls for civil rights and greater kindnesses, agents of the Establishment have attempted to use language as a sword wielded against minorities and as a shield to preserve a status quo where all rights were not distributed equally. “Grammar is [not] a kind of objective and neutral force… [it’s political],” Baron adds.

In his view, the biggest misconception people have about the increasingly commonplace use of the singular ‘they’ for non-binary people is that it is a modern invention. In truth, this is actually a rewrite of historical events.

“[People think] the singular ‘they’ is some kind of innovation, some kind of new feature that is being imposed by people who have no right to direct language,” he states.

As Baron goes on to explain, the singular ‘they’ has been in standard usage for centuries. “It goes back at least to the 14th century, probably a bit earlier, in terms of both referring to an indefinite member of the class and even to known individuals whose gender is either irrelevant or needs to be hidden.”

He continues: “Jane Austen uses the singular a couple [of] hundred times in Pride and Prejudice; Shakespeare uses it.”

Part of the reason Baron thinks “they” is so successful as a solution to the “missing” third person, gender-neutral pronoun, is its widespread use by those who purport, in his words, to not “care about gender at all, who don’t give it a second thought, or even who oppose gender rights for gendernon-conforming or non-binary people”, often without realising what they’re doing.

Baron’s book, and indeed talking to him, offers hope for the pronoun battle the LGBTQ community finds itself waging with those who would deny many the right to be acknowledged in the manner in which they identify, who want to refuse others the freedom to be represented with the language that best aligns with our understanding of our bodies, our genders, our very truths.

The non-binary flag

“In a longer-term perspective, gender nonconformity, non-binary individuals are going to become much, much less conspicuous,” Baron says of future conversations around these pronouns.

“It’s going to be [ordinary], rather than, you know, we’re here, we’re queer… and maybe if the political edge gets softened, there will be less pressure on the pronoun system.”

Baron doesn’t envision a perfect “Star Trek world where pronouns will no longer have any gender”, referencing a US study in which the majority of trans people surveyed preferred to use masculine or feminine pronouns.

But he does see in our future continued proliferation and acceptance for the singular ‘they’ in tandem with an acceptance of those who choose to use it, as well as fresh attempts at imagining and coining new gender pronouns.

“[People] are still saying ‘OK, well, you know, maybe I don’t like singular ‘they’ so much, I don’t like the other coined suggestions…” he muses as we wrap up our interview.

“People are always trying their hand at inventing words. That’s how language evolved. Every word that we use was invented by somebody at some point.”

‘What’s Your Pronoun? Beyond He and She’ is available now.