When Keith met Andy: New biography recounts moment Haring and Warhol’s worlds collided

To celebrate the release of Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring by Brad Gooch, out now, Attitude is able to share the below exclusive extract

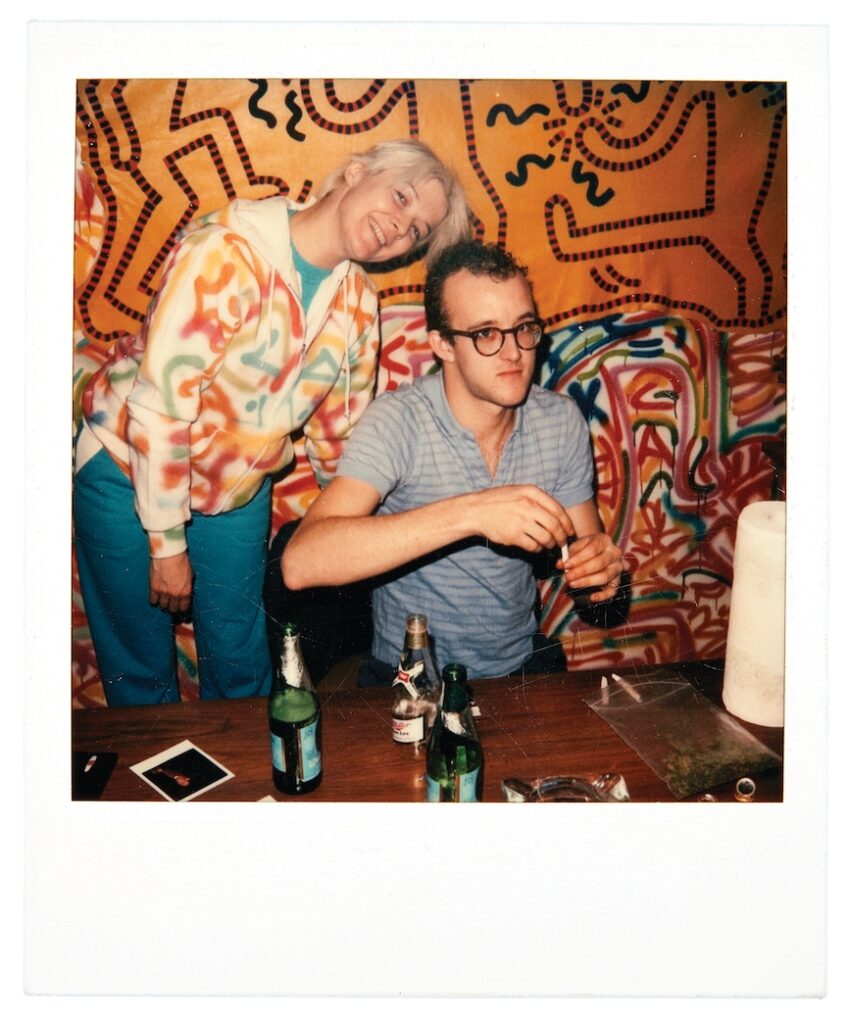

The friendship with Warhol truly clicked with the opening of the Fun Gallery show. Haring either skipped over the earlier studio visit in telling the story or simply misremembered, often dating his first meeting with Warhol to the opening of the Fun show on a wintry night in early February 1983, with snow piled in front of the double storefront on East Tenth Street near Second Avenue. Fun Gallery was run by Patti Astor and Bill Stelling and named by Kenny Scharf, who held the gallery’s first show in September 1981, followed later by Jean-Michel Basquiat in November 1982. Patti (born Titchener, in Cincinnati) Astor, with her platinum hair, high-gloss lipstick, and marquee name, was something of a movie starlet in the underground film scene, having starred in Eric Mitchell’s Unmade Beds and Charlie Ahearn’s recently wrapped Wild Style, in which she played a “lady reporter” whose unlikely beat was the uptown graffiti and hip-hop scene. Astor claimed as inspiration Haring’s “one-off” shows at Club 57 and Mudd, as he “never cared if anything sold, or if the works were on paper, or if people turned up or if they didn’t.” She was especially inspired by the Beyond Words show at Mudd, as Fun was mostly a graffiti gallery, an underground railroad station connecting the East Village with the art space Fashion Moda and the South Bronx, and many of her costars from Wild Style showed at the gallery, including Fab 5, Futura, and LEE.

When Fun opened in 1981, few other galleries could be found in the East Village. The concept of an East Village art gallery was jokey. Yet, within two years, twelve galleries appeared — Piezo Electric, P.P.O.W., Pat Hearn — and the following year, twenty more. By 1984, at the height of an East Village art boom, more than seventy commercial galleries were operating in the neighborhood. One of the first to name this trend, and contribute to its spiking, was, again, Rene Ricard, in an essay — titled “The Pledge of Allegiance” and loosely pegged to Kenny Scharf’s second exhibition at Fun Gallery — that appeared in Artforum in November 1982. Ricard was not a neutral critic. He had dropped by Fun Gallery each morning for a coffee and had convinced Basquiat to show at the gallery, saying, “Jean, chill with Patti. Come home. Come on. She’ll be straight with you.” (Basquiat spent most of his opening in a corner, arguing with his new girlfriend, Madonna, known for her performance at Haoui Montaug’s No Entiendes cabaret at Danceteria.) Yet the point of Ricard’s piece was that only a charmed circle of insiders, a “conspiracy of excellence,” could report from the cultural front.

“Patti Astor is a beautiful example of what John Ashbery would call ‘An Exhilarating Mess’ in operation,” he wrote. “She isn’t a businesswoman. Her opening of the gallery coincided with (or caused) a definite shift in the social pattern of the last two years. Fun is the apotheosis of what Edit deAk has called ‘Clubism,’ but just happens to be taking place in an art gallery.”

Keith did not need to show his work at Fun Gallery. His big opening at the Shafrazi Gallery had been just four months earlier. Yet he wished to support Patti Astor and her new space. He had given her a painting to help her survive the early months. “I held firm on the price that Keith and I had agreed upon, and we sold it for the asking price of $1,800,” Astor said. Even the installation leading up to the show at Fun was entirely in the spirit of “Clubism.” Said Haring, “My exhibition at Fun Gallery was really a reference to the whole Hip-Hop culture,” as he and LA II “bombed” the gallery in spray paint and were so carried away that they even spray-painted the snow piled out front and Astor’s white hoodie sweatshirt. “Every day, there would be forty young graffiti artists from the ages of ten to eighteen hanging out in the gallery, smoking pot and chewing grape-flavored bubblegum,” said Bill Stelling of the week or so before the opening. “That’s what I remember: the gallery smelling like bubblegum and marijuana.” Haring and LA II collaborated on a batch of plaster-cast Smurfs — viewer favorites, as Smurfs were not only TV cartoon characters but also the name of a new move in break dancing, “the Smurf,” or “Smurfing.”

Haring wanted to use the opportunity to show something new, so he decided to work with synthetic leather hides. Recently at Paradise Garage, he had met Bobby Breslau, who introduced himself and offered to share a joint. A “short, interesting-looking Brooklyn guy,” as Haring described him, Breslau was friendly with the “godlike” Larry Levan and brought Keith up to his deejay booth for the first time. The occasion was an installation by Haring of painted walls in a room off the dance floor, and Breslau said, “What? You have this thing here and you haven’t even met Larry?” Breslau also turned out to be a friend of Warhol’s as well as being the designer who made Halston’s leather handbags in the seventies. (A framed letter from fashion editor Diana Vreeland in Breslau’s apartment praised him: “You are to leather what Cellini is to gold.”) More than a decade older, and wiser in the ways of art, social life, and fabrication, Breslau was soon a valued member of the Keith Haring band. “He becomes my Jewish mother!” Haring said. Whether cause or effect, Breslau was perfect for helping Haring with the works on leather he exhibited at Fun, as he led him to the pelts and hides he covered with marker and acrylic paint and hung over the graffiti’d walls. Haring also showed diagonal, hard-edge wood tables carved by Kermit Oswald that he and LA II painted pink-red and suffused (as they did the office telephone) with their nervy marks.

The opening turned out to be “even more funky than the Tony Shafrazi opening had been,” Haring said. A thousand people jammed into the single-story building that was shaking from the overcrowding, most winding up in the cold backyard, where Juan Dubose was deejaying. At the height of the opening, Stelling turned to Astor and said he thought their little gallery was going to either levitate into the sky or crash into the basement. “The opening attracted a remarkable mix of Puerto Rican kids from the neighborhood and the elite of the art world,” said Jeffrey Deitch. Haring’s simple invite was a nod to break dancing, illustrated with three bodies twisted into the letters F, U, and N. He also printed posters to be given away. Yet, during the evening, someone came running in and said to Patti Astor, “The neighborhood kids are selling Keith Haring posters up the street for five dollars!” She needed to go outside and tell them to stop. When Andy Warhol finally arrived, he instantly twigged the art and the scene, as he was now seemingly as much in search of the sixties as the Club 57 kids who were imitating him: “Then to the Keith Haring opening (cab $4). It was on the Lower East Side, at the Fun Gallery, it’s called. So we walked into the place and there’s Rene Ricard, and he’s screaming, ‘Oh my God! From the sixties to the eighties and I’m still seeing you everywhere!’ . . . And Keith’s show looked good, it was his pictures hanging on a background of his pictures. Like my Whitney retrospective show was — all hung on top of my Cow wallpaper.”

To some people’s surprise, though, nothing from the show sold. “Just one freakin Smurf,” said Astor, who felt the work too adventurous for her collectors, who showed up in their limos the next morning.

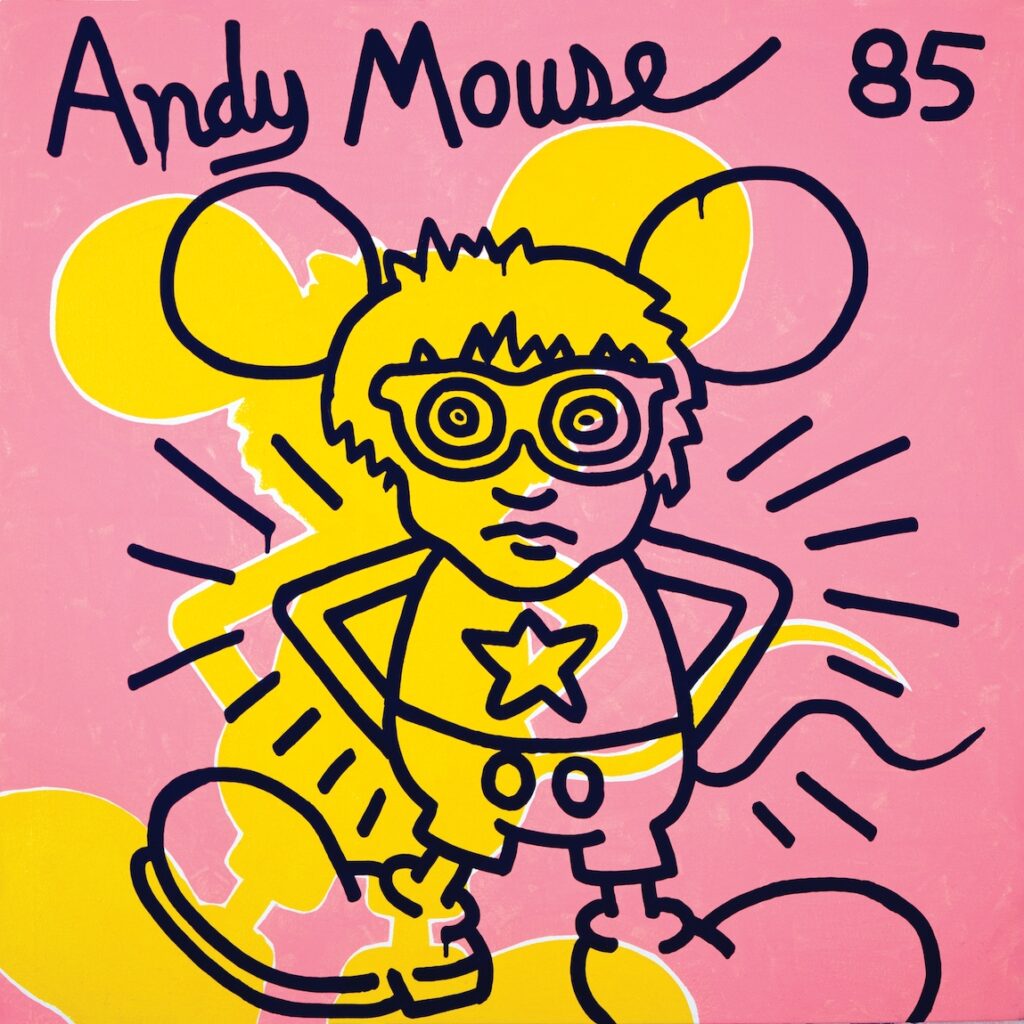

Soon after the show, Warhol invited Haring up to the Factory, and they talked about trading artworks. “He let me look through his prints, and I saw a series of really erotic prints — guys fucking guys and closeups of dicks,” Haring said. “I chose one print of a guy fucking another guy, and he said, ‘I’ll make you a painting of it.’” Warhol printed the image in black on a white canvas in close-up, as a near abstraction but with the subject matter still evident: “That was my first Warhol painting. For it, I had to trade him I don’t know how many things, because the trade was sort of value for value — and his stuff was very expensive. So, his manager, Fred Hughes, arranged all that, because Andy didn’t want to be involved in this part of the trade.” Haring then hung the Warhol above the toilet in the bathroom at 325 Broome.

According to Makos, “Andy was just so impressed when Keith was giving out those buttons of the baby. He was jealous of how Keith was like an advertising agency unto himself. That was the cleverest thing any artist at the moment was doing. Whenever you went to anything, whether it was Paradise Garage, anywhere you went, Keith was there, and he had a bag of those buttons, and everybody wanted one of those buttons. He made everyone aware he was a player. That was something that Andy loved and admired about him.” Of Haring’s developing friendship with Warhol, Scharf said, “It was another loop in the roller coaster he was on, and it rode him pretty high.”

Three days after Warhol attended the closing of Haring’s show at Shafrazi, he recorded in his diary, “Jean Michel Basquiat who used to paint graffiti as ‘Samo’ came to lunch, I’d invited him.” Like Haring, Basquiat had a tremendous art crush on Warhol and was even more of an active stalker. Although Warhol occasionally bought postcards and T-shirts from him, when Basquiat tagged the front door of a building Warhol owned on Great Jones Street with “Famous Negro Athletes,” Warhol gave instructions that he not be let inside. His mood began to soften when his own Swiss art dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, started promoting Basquiat and when Basquiat became romantically involved with Paige Powell, the advertising director of Interview.

Copyright © 2024 by Brad Gooch. Printed courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.