How Section 28’s painful legacy is still being felt three decades on

Matthew Todd explores how the most vicious piece of anti-gay legislation in modern times continues to affect the LGBT community.

By Will Stroude

This article was first published in May 2018.

In May 1988, Section 28, the most anti-gay piece of legislation of modern times, became law amid a tsunami of fear and hatred. By the mid 1980s, several years after the first reports of a disease then referred to as Gay Related Immune Deficiency Syndrome (GRID), because it was said to affect mainly gay and bisexual men, the UK was in a state of panic.

Instead of calmly educating the public about how we could all protect ourselves from HIV, and what became known as Aids, the right-wing media poured petrol on to the fire, pointing the finger of blame at gay men, to create support for the party of traditional moral values.

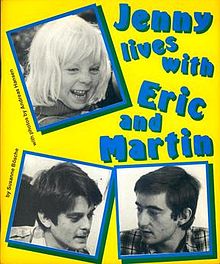

In 1986, a year before a general election, The Sun, then edited by Kelvin MacKenzie, plastered a book over its front page that it claimed left-wing councils were pushing on young children.

The story bore the headline “VILE BOOK IN SCHOOLS”.

Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin was a sweet, Danish teaching aide that depicted a young girl living with her two gay dads.

MacKenzie’s dog whistle message was that Labour, who the year before had committed to LGB rights, supported paedophilia.

In fact, only one copy of the book had bought for a teaching centre and was intended for use with older children — and then only with parental permission.

After winning that summer’s election, with a campaign that included overt homophobic posters, at the Conservative Party Conference in October 1987, then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher persisted, denouncing Labour councils in her main speech.

“It’s the plight of individual boys and girls that worries me most,” she proselytised. ”Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught they have an inalienable right to be gay… all of these children are being cheated out of a sound start in life. Yes, cheated!”

Two Tory MPs, Jill Knight and David Wilshire, revived an idea by Lord Halsbury, proposing an amendment to the Local Government Bill, which stated that local authorities “shall not intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality” or “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.”

In May 1988, despite public debate and demonstrations, it was enshrined into law that a generation of young gay and lesbian people could only be taught that their relationships, their family, their love was not real, but was “pretend”. And if teachers tried to say anything different, they would be breaking the law.

Jump forward 30 years. Section 28 was repealed in 2000 in Scotland, and three years later in England and Wales. It was never used to prosecute a school or local authority. The age of consent is now equal; we can serve in the armed forces, adopt, marry, and we have protections under the law.

Many of us thrive and there is much to celebrate. But as a community we still live with disproportionately high levels of depression, anxiety, thoughts of suicide, and addiction with a raging drug crisis. I know because I’m affected by those issues, too.

I was 14 years old when Section 28 (also known as Clause 28) came in. During my adult life I’ve had a ton of therapy dealing with the consequences of growing up in an era in which being gay was considered unnatural, and I continue to work on my recovery.

In my book, Straight Jacket, I write about how these patterns of low self-esteem and self-destructive behaviour are more common in the LGBT+ community than they should be. Is this all because of Section 28? No. But did Section 28 contribute significantly? I believe the answer is yes, absolutely. The legislation certainly had an impact on teacher and actor Chris Woodley who started secondary school in Bromley, South London, in 1993.

As a young adult he became a teacher to stop kids going through what he did. His show about Section 28, Next Lesson, was a hit in Edinburgh last year.

“I was spat at, sworn at, shoved around, belittled, bullied and abused on a regular basis,” he told me of his time at school. “Homosexuality wasn’t discussed and it certainly wasn’t seen as normal. The legislation put a stop to any dialogue on matters surrounding sexuality, meaning that many students had no voice and nowhere to turn for support. I eventually realised the huge effect it had had on my confidence and feelings of self-worth.”

Some teachers have told me they didn’t feel overtly restricted by Section 28 — or didn’t allow themselves to be. John Yates-Harold was a teacher at the time and made a point about trying to be open. He was called a paedophile during his training just because he was a gay man who wanted to be a teacher.

On the whole, he says, he was supported, although at one school with predominantly Muslim pupils, he censored himself, perhaps because of fear of Section 28. He believes the legislation confused many teachers.

“I remember developing a close friendship with the woman who trained me in relationship and sex education,” he told me. “Conversations with her around Section 28 were interesting as she was aware of it but was completely unsure and baffled about how it actually related to our teaching. This seemed to me to be the case with other teachers I knew at the time.”

Other teachers were aware and took risks to help their students. But many did nothing and just turned a blind eye to homophobia.

One man told me, when he was at school he was regularly abused and spat at, and eggs were thrown at his house. “Teachers ignored it all, until one day I bit back at a comment. A teacher held me back after class and told me, at the risk of losing her job, she wanted to support me, and could connect me with her gay friends, and simply passed on the number for the Gay and Lesbian Switchboard, telling me never to tell anyone she had done so.”

THE LEGACY OF SECTION 28

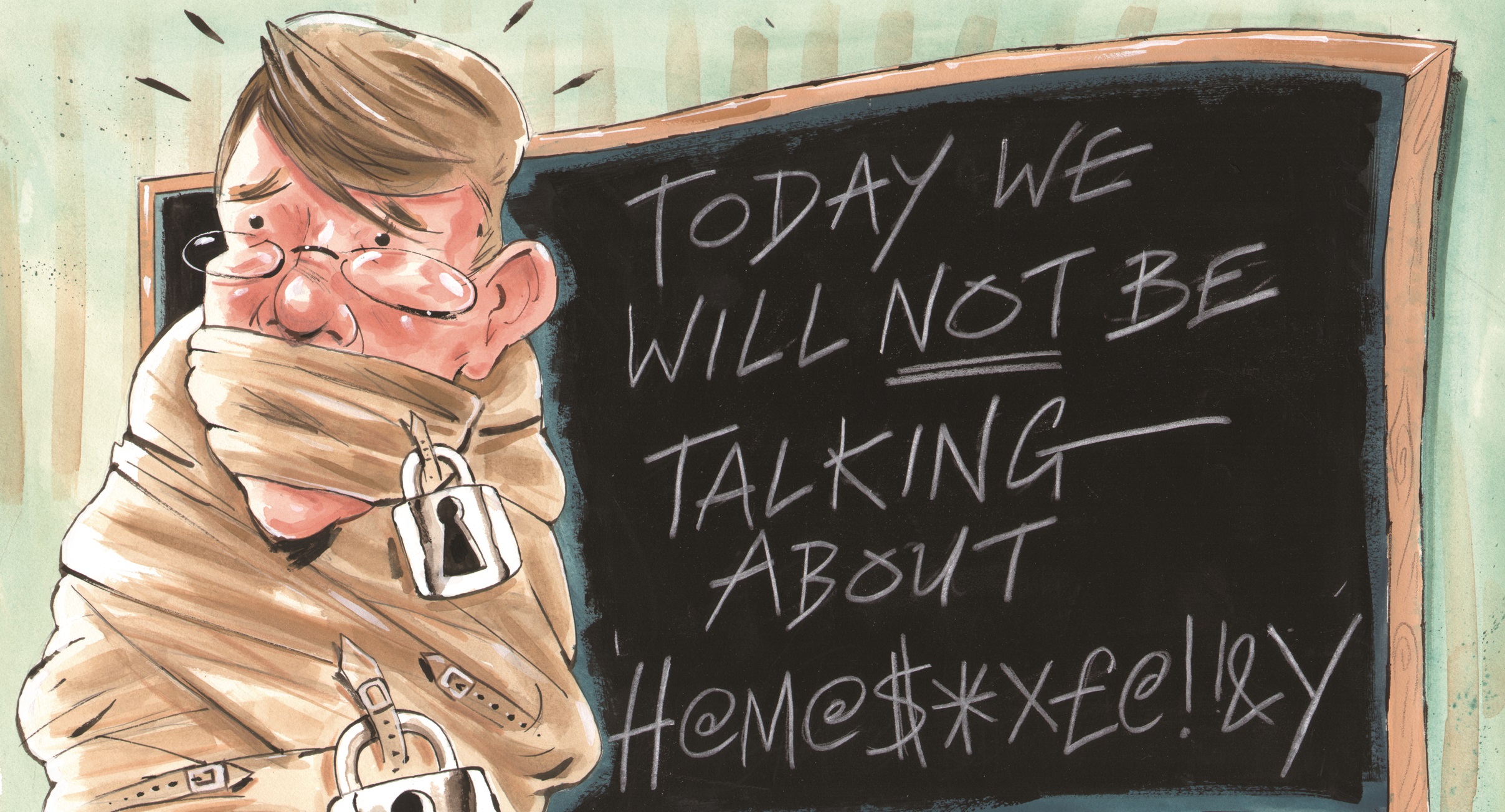

Illustration: Russ Tudor Cartoons

What effect did making the identity of young gay men invisible have on us? A friend of mine who is struggling to control an alcohol problem, told me simply, “It pretty much ruined my life.”

Others went into more detail. Paul lives in London. He was 13 in 1988. He told me that the constant homophobic bullying he endured made him physically and mentally ill. He didn’t want to go to school, and was constantly in fear of being attacked.

“Once someone bashed in my head with a brick,” he says. “On another occasion I was walking home from school and the group of lads who used to bully me caught up with me. I got away from them, but before I could reach home, I had a terrible case of diarrhoea. I made such a mess of myself by the time I reached home, I couldn’t do anything apart from get in the shower and take my clothes off. I had a very black depression which made me suicidal.”

Teachers knew about the bullying but did nothing to stop it.

“I believe the silence was as a direct result of Section 28. That’s what it and Margaret Thatcher did to people.”

Many of the people I spoke to during my research told me that teachers explicitly said they were not allowed to talk about homosexuality in class.

“We had life-skills lessons and were told in no uncertain terms not to go to the teachers if we thought we might be lesbian or gay,” one man, who is now in recovery for mentalhealth problems and alcohol and substance abuse told me.

“I felt isolated,” he continued. “That instilled fear and self-doubt that shaped my future full of anxiety. The consequences to my psychological and physical health were damaging. I now have cirrhosis of the liver. The suicide attempts were due to a number of factors, but the anxiety that stemmed from my childhood was one of them.”

There’s evidence now that if you tell children they aren’t good enough, over and over, as adults, they’ll be more likely to have depression, body-image disorders and suicidal thoughts — as well as suffer from addictions.

This was true for Charles Donovan, a writer now in his forties, who was at boarding school when Section 28 came in. Aged 16, two years after its implementation, he was so terrified after other boys found a gay magazine under his bed that he ran away and ended up spending a night on the streets, having sex with men for money. When he returned to school, telling teachers that the magazine was planted, one member of staff did awkwardly try to support him.

“He had to do it in code — it was tortuous and didn’t go anywhere,” Charles told me. “He couldn’t just broach the subject in a direct manner. That would have jeopardised his job.”

Years later, Charles developed a drink and drug habit and, on one occasion when high, he had an accident in which he broke his back, leaving him partially disabled.

Therapist Simon Marks, who works at the UK’s only LGBT-specific drug and alcohol service, Antidote, told me: “People we see, seeking help with their relationship with drugs, often talk of the negative messages they received growing up. A lot of them attribute those messages to school where they weren’t able to seek help or find reassurance.

“A big part of the problematic drug use that we are seeing now is because of Section 28,” he adds.

Section 28, ironically, galvanised the gay community, forcing it to become more vocal and political. Peter Tatchell and OutRage staged ever-more-high-profile acts of civil disobedience and actor Ian McKellen, who came out in protest, and a group of other notable figures formed the Stonewall lobbying group. It was a brave move by McKellen, at a time when few high-profile people went public about their sexuality for fear of damaging their career.

Today, while many schools do outstanding work to support LGBT+ youngsters, the ghost of Section 28 lingers in many classrooms.

Chris Woodley said Section 28 left a confused feeling in the education system about what could and could not be discussed in schools. “Even today, the way in which we deliver relationship and sex education [RSE] in this country needs to be addressed; without open and honest conversations about RSE, we are at risk of failing LGBT+ young people.”

Teacher John Yates-Harold, who has since published a teaching resource called Kings, Princesses, Ducks & Penguins, agrees. “Sadly,” he said, “there are educators who still think that Section 28 exists and that they can’t, and don’t know how to, support children and young people who identify as LGBT+.

“The word needs to be spread far and wide that we have a duty to support all our pupils, whatever their sexuality or sexual identity.

Only when we do this can we consign Section 28 to the dustbin of history where it belongs.”

HEALING THE WOUNDS?

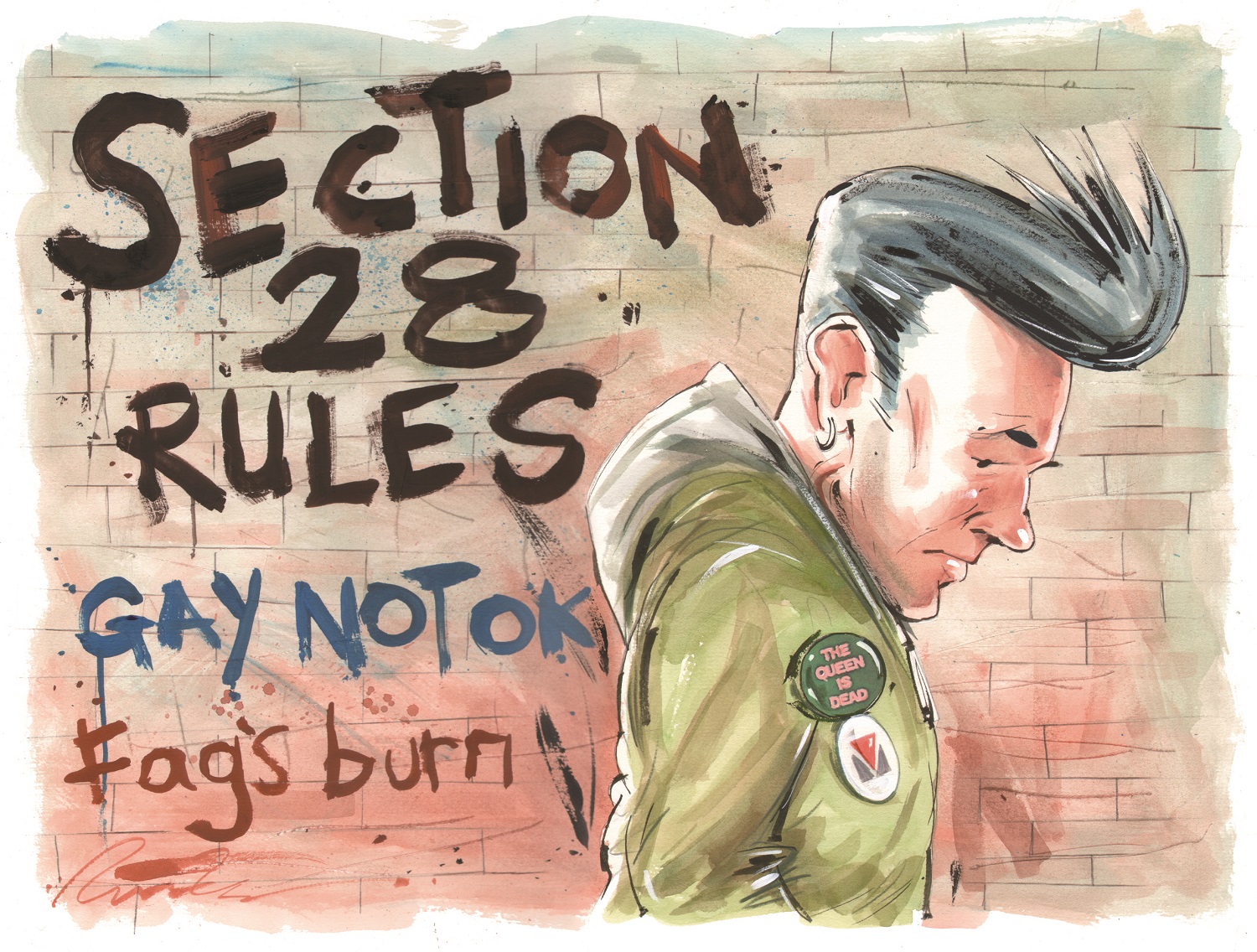

Illustration: Russ Tudor Cartoons

The Tory Party would love the memory of Section 28 to remain in the dustbin. In 2005, in an historic issue of Attitude, with Tony Blair becoming the first serving Prime Minister on the cover of a gay magazine, the then Conservative leader Michael Howard admitted that Section 28 was a mistake. Four years later, David Cameron apologised for it.

The debate about whether or not the Tories can be forgiven rages on, and is, of course, influenced by people’s personal political views. There are plenty of LGBT+ Conservative voters, and it’s important to acknowledge that many gay Tories worked from within the party to change the policy. It’s true that David Cameron risked unpopularity with his grassroots supporters when he pushed through equal marriage.

But even so, when it came to the vote, more than half of Conservative MPs stood against same-sex marriage.

There’s an irony that Section 28 also damaged the Conservative Party, forging life-long Labour voters out of a huge number of people.

Charles Donovan believes that Section 28 is unpardonable, and nothing the Conservative Party could ever do would rehabilitate them in his eyes.

“Cameron’s miraculous conversation to the gay cause was cynical. What some people don’t realise is that Section 28 didn’t have to be actively used to have an effect; it had a massive cultural effect regardless.

“It guided public opinion. It profoundly affected school culture and environment. It dissuaded a generation or more of LGBT+ youngsters from seeking guidance and help. I think it had a ruinous and permanent effect on vast numbers of people.”

Today there is another reality, far removed from the shiny, smiley cross-party acceptance at Parliamentary cheese-and-wine receptions held to engage the LGBT+ community that reflects the true impact of Section 28.

Thirty years after the legislation was introduced, a quarter of all young homeless people are estimated to be LGBT+, queer people of colour are disproportionately affected by HIV, LGBT-inclusive relationships and sex education is still considered controversial, while suicide and mental health problems still remain disproportionately high.

Indeed, a friend of mine in his thirties took his own life in the weeks that I was researching this article.

It seems we are still living with — and dying from — the effects of a truly oppressive piece of legislation from 30 years ago and the culture that created it.

Today, none of the parties are doing enough to meaningfully address the enduring legacy of Section 28.

Straight Jacket, by Matthew Todd, is available in bookshops and online now. matthewtodd.net