Holocaust Memorial Day: Why no one seemed to stand up for gay men during Nazi atrocities

1920s and early '30s Berlin was home to one of the liveliest gay scenes in the world. By 1945, up to 100,000 gay men had been arrested and thousands lay dead.

By Steve Brown

Words: Hugh Kaye

It’s more than likely that everyone reading this has heard of Oskar Schindler, who saved more than 1,100 Jews from the Holocaust during WWII.

Some of you might also know of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who pulled people out of the jaws of the Nazi killing machine. Both have been portrayed on film.

Meanwhile, Nicholas Winton has been described as the British Schindler after he organised the rescue of 669 Jewish children in what became known as the Kindertransport.

Fewer of you will know that Hermann Goering’s younger brother, Albert, was responsible for saving the lives of Jews, too. Maybe just a handful of you know that a Nazi officer, Major Karl Plagge, while running a forced-labour camp, tried to keep hundreds of Jews from being executed or deported to extermination centres in Poland.

Some civilian workers in Auschwitz even smuggled in food, letters and guns to Jewish prisoners.

The point is there were people who put their own lives in jeopardy to save Jews from the Holocaust. There were nuns, teachers, social workers, farmers, even royalty (the queen of Belgium).

And their actions must for ever be celebrated; their bravery is unsurpassed in human history. Dismissing the dangers, they, more often than not, hid or protected people they didn’t even know.

But if you Google “did anyone help/save gay men from the Nazis?” you get exactly zero relevant links. No Schindlers, no Wintons, no Plagges. None.

Some Jewish children who were saved have grown up and are gay, and have testified about brave people who helped them. But that’s not the same thing.

Instead, gay men were rounded up almost immediately after Hitler took power in January 1933. Any gay man brought to the attention of the police could be arrested and have his fingernails pulled out or his bowels punctured.

Others were made to stand to attention for hours on end or march 25 miles every day. Many were never even given a trial.

Those who didn’t end up in prison cells were sent to concentration camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, the underground rocket factory at Dora-Mittelbau, where they were often given the most dangerous tasks, and the back-breaking stone quarries at Flossenburg.

Wherever they ended up, they were treated as the lowest of the low. Some had their testicles boiled off, others had large pieces of wood inserted in their rectum. They were tortured and used as guinea pigs for the Nazis’ bizarre and often pointless experiments.

They faced persecution not only from the SS – some of whom used them for target practice — but also from other prisoners and many were beaten to death.

In some cases, they weren’t even allowed to talk to other prisoners.

Also disturbing are the results of by study by prominent LGBT scholar Rudiger Lautmann which shows that survival rates for gay men sometimes relied on them coming from the middle or upper classes or being married bisexual men and those with children.

Lesbians were seen as far less threatening by the National Socialists, who believed they could still “serve the state” by being mothers.

That’s not to say they weren’t persecuted but those who chose to be more discreet were, in general, left alone and even those rounded up were never made to wear the infamous pink triangle.

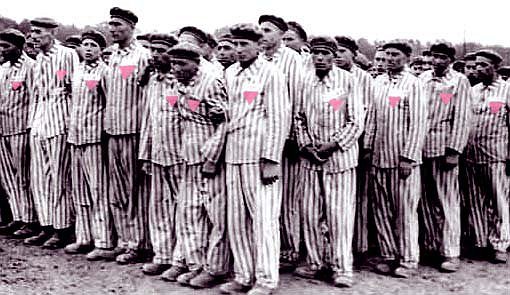

Between 1933 and 1945, it’s believed about 100,000 LGBTQ people were arrested. Up to 15,000 gay men were sent to camps where possibly as many as 60 per cent of them died.

Compare this with the death rate of other minority groups and you’ll see that about 35 per cent of imprisoned Jehovah Witnesses perished and 41 per cent of other political prisoners. Of course, those numbers are tiny compared with the murder of millions of Jews.

They were marked for almost immediate death whereas gay men were exposed to a programme known as Extermination Through Work.

But another difference is that at the end of the war, the survivors of the camps were liberated and, in time, compensated. Many gay men, identified by the pink triangle, were put back in prison, under a statute known as Paragraph 175.

Their years of suffering in the concentration camps did not count as part of their sentence.

The law remained in force in what became West Germany until 1969, when homosexuality was decriminalised for those over the age of 21. Paragraph 175 was not repealed in full until 1994, when the age of consent was lowered to 14, matching that for heterosexuals.

Even then, unlike other victims of the Nazis, the approximately 4,000 gay survivors were not acknowledged or compensated for the persecution they suffered while the years that SS guards worked in the camps counted towards their pension entitlement.

The memorial plaque at Sachsenhausen concentration camp, Germany

But why did no one want to help gay men?

SS leader Heinrich Himmler revealed the Nazi state’s view of gay men. Estimating the number of homosexuals in Germany as somewhere between from one and two million, close to 10 per cent of the country’s men, he said: “If this remains the case it means that our nation will be destroyed by this plague. We must exterminate these people root and branch… the homosexual must be eliminated.”

Adding the number of homosexuals to the number of men who died in the 1914-18 war, Himmler estimated that this would equal four million men.

“If these four million men are no longer capable of having sex with a female, then this upsets the balance of the sexes in Germany and is leading to catastrophe. A people of good race which has too few children has a one-way ticket to the grave. Therefore, we must be absolutely clear that if we continue to have this burden in Germany, without being able to fight it, then that is the end of Germany, and the end of the Germanic world,” the lord of the SS added.

Nazi policy toward homosexuals became stricter from mid-1934, owing, among other reasons, to the activity of the homophobic Himmler and the growing power of the SS under his leadership.

He saw Ernst Roehm, the head of the SA, the original stormtroopers and Nazi paramilitary, as a threat.

Roehm was a known homosexual. A supporter of Hitler from the very beginning, his position looked secure. But Himmler and others managed (without too much difficulty) to convince their Fuhrer that Roehm was planning a coup, while the army was wary of the SA’s power.

Roehm’s fate was sealed and he was murdered in July 1934 during the Night of the Long Knives.

Whereas the Nazis had, to an extent, tolerated homosexuals while Roehm was alive, following his death things started to get much worse and the scope of Paragraph 175, in force since the 19th century and which made homosexuality illegal, was broadened: men were arrested for kissing each other or simply looking at each other in an “immodest” way.

In a 1991 documentary, We Were Marked with a Big A, one interviewee says: “A fearful period began because essentially you weren’t caught in the act, but on suspicion and you were punched and beaten until you named names.”

The A of the title was a symbol which pre-dated the pink triangle and stood for arschfiker (arse-fucker).

The police established lists of homosexually active men. Significant numbers were arrested, of whom an estimated 50,000 received severe jail sentences, served in brutal conditions.

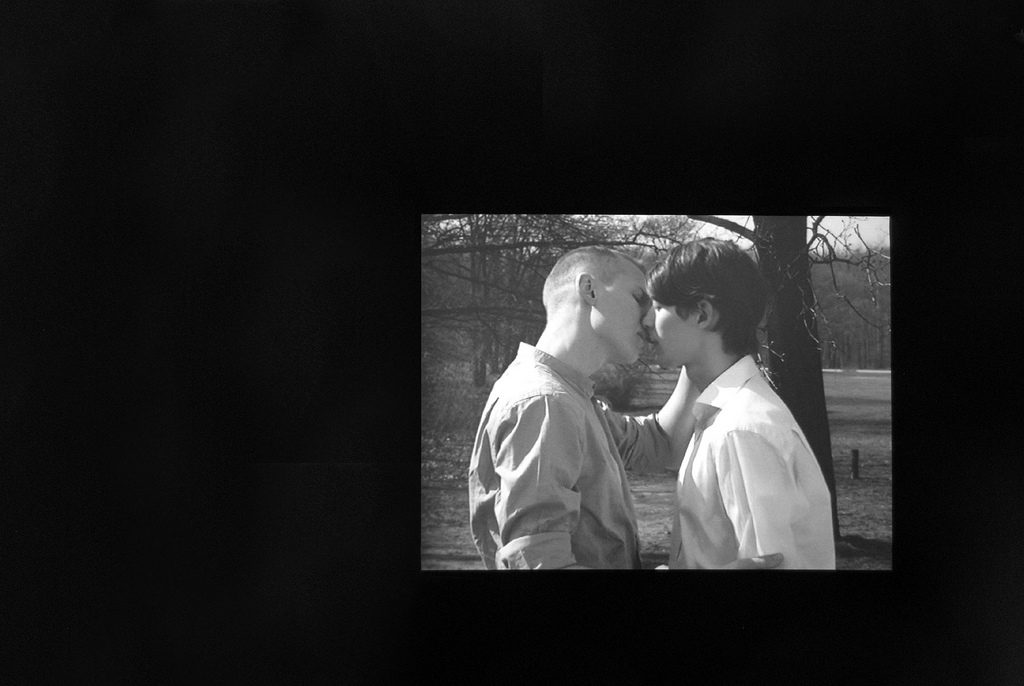

A video of two men kissing plays on an eternal loop at the Memorial to Homosexuals persecuted under Nazism in Berlin

A few lucky ones were released but others went to police prisons, the rest were deported to concentration camps. Many died from exhaustion. A large number took their own life.

As for members of the public, German society at the time was extremely conservative, sanctifying what some now call family values. Gay men were seen as a threat to that.

The Great War had given Germans an idea of manliness into which gay men did not, in their eyes, fit. They were seen as feminine, unfit to be soldiers, as well as cowardly and even unpatriotic because they did not “create” children.

Gay men simply could not, people believed, be good fighting men. Indeed, they were more likely to disrupt military cohesion and morale. Whereas Jews might be worth saving, gay men – branded as sexual predators and a contagion – were not.

At the very core of Nazi beliefs is the idea of conforming to the “social norm”. Homosexuals were seen as inferior, often with animal instincts.

Religious and medical teachings furthered this view. Propaganda in Nazi newspapers was almost endless.

And ironically, the relative freedom LGBTQ people had enjoyed before the rise of the Nazis didn’t help.

In the 1920s, Berlin had about 100 gay and lesbian bars or cafes – places such as Bull and Eldorado, where drag queens gave dancing lessons to both gay and straight customers. Vienna had about a dozen gay cafes, clubs and bookstores.

Paris had a gay nightlife and parts of Italy had gay districts. Films started to be more sympathetic to gay characters and even media barons seemed to realise that LGBTQ people bought newspapers.

Prior to the rise of the Nazis, the German MPs in the Reichstag were thought to be on the verge of repealing Paragraph 175.

All this provoked their opponents. The conversation.com reports that: “A French reporter, bemoaning the sight of uncloseted LGBTQ people in public, complained ‘the contagion is corrupting every milieu’.

The Berlin police grumbled that magazines aimed at gay men, which they called obscene press material, were proliferating and a Parisian town councillor in 1933 called it ‘a moral crisis that gay people could be seen in public.

‘Far be it for me to want to turn to fascism,’ the councillor said, ‘but all the same, we have to agree that in some things those regimes have sometimes done good’.

Although not every German was a member of the Nazi party, a huge majority at least turned a blind eye to the persecution and atrocities. Others offered tacit support.

History shows that in 1933, 853 men were convicted of homosexuality in Germany. The number shot up in 1936 to 5,320 and rose again two years later to 8,562.

In 1937, the official SS newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps, estimated that there were two million homosexuals in Germany – and called for their deaths.

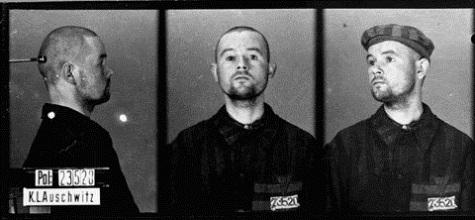

Kurt Bruhn

The seeds of the Holocaust had been sown and men like Kurt Bruhn paid the ultimate price.

Born in Bavaria in 1913, he was one of the relatively small number of gay men sent to Auschwitz (some historians put the number at 77).

He had worked as a clerk and arrived at the death camp in November 1941 where he was tattooed with the number 23520. He died 11 months later, aged 28, one of at least 43 gay men to perish there.

Albrecht Becker was another gay man to suffer under the National Socialists. An actor, photographer and production designer, he was born in Thale, Germany in 1906.

At the age of 18, he met 27-year-old historian Joseph Abert, and they began a relationship which would last 10 years. But Albrecht had had his photograph taken by a wine merchant whose house was searched by the Gestapo who found the snapshot in a safe.

Albrecht was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison. As the war turned against Germany, he was released but forced to serve in the Wehrmacht on the Eastern front until 1944.

He survived the fighting and died back home in Germany in 2002, aged 95, after appearing in the documentary Paragraph 175.

Joseph also survived arrest and imprisonment at the hands of the Nazis.

Another to suffer was Heinz Dormer who, under pressure, had joined the Hitler Youth in October 1933. Less than two years later he was accused of sexual activities with other members of his troop.

Heinz was to spend large parts of the next two decades in concentration camps and prisons. He also appears in Paragraph 175 and describes a “singing forest” where other inmates were hung from trees, screaming in agony as they were pretty much crucified, until they died.

Heinz wasn’t finally released from jail until 1963. His application for reparations, for his suffering, was rejected as recently as 1982.

Musician Wilhelm Heckmann was arrested in 1937 and sent to Dachau, just outside Munich “in protective custody”.

In 1939, he was transferred to Mauthausen in Austria, where people died daily from exhaustion, malnutrition (an average inmate weighed 88lb/40kg) or after being forced to take icy showers and left standing outside without any clothing.

In later years, they died in mobile gas chambers or on forced death marches.

Wilhelm survived but on his release struggled to make a living because of the years of heavy labour he was forced to undertake in the camp. The stones he was forced to carry up and down the 186 “Stairs of Death” all day weighed 110lb (50kg).

In 1954, he applied for compensation. Having waited six years for a decision, his application was turned down by the German government who noted he had only been “imprisoned as a homosexual because of crimes against Paragraph 175 of the penal code”. He died in 1995 at the age of 97.

Friedrich-Paul von Groszheim was one of 230 men arrested by the SS in Lubeck in January 1937 on suspicion of being gay. He served ten months in jail and held in a cell with no heating or toilet facilities, and given very little food.

He was re-arrested in 1938, tortured and castrated before being released again. After being arrested for a third time, in 1943, he was sent to the concentration camp at Neuengamme in northern Germany as a political prisoner.

An article in The Independent in 2001 reported: “Martin Gilbert’s recent book, Never Again, purports to be ‘a comprehensive account of the holocaust.’ Yet the fate of non-Jews merits only one two-page chapter and the mass murder of homosexuals is accorded a single sentence.”

So, there you have it. Our “differentness” was all that was needed. It’s why no one seemed to have even considered hiding gay men from the clutches of the SS and the Gestapo.

And what to take from this? As we mark Holocaust Memorial Day, it may be 77 years since the liberation of Auschwitz, but the Far Right are on the rise again, backed either openly or more surreptitiously by mainstream politicians in some countries.

Not least of all in Germany, where the far-right Alternative for Germany party has enjoyed success, winning 92 seats in the Bundestag (the federal government) less than five years ago.

In Saxony-Anhalt a year earlier, they took 24 per cent to become the second largest party in the state parliament.

Some of their politicians have called for homosexuals to be jailed, have vowed to repeal gay marriage – branding it a “national death” – and reportedly posting an obituary of the “German family” on their website. Meanwhile, anyone with HIV seems to be a target for persecution.

Meanwhile, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, who succeeded Angela Merkel as the leader of Germany’s Christian Democratic Union party, has been quoted as likening gay marriage to incest and claiming the best way for a child to be brought up is by a mother and a father.

Last year, The Guardian reported that AKK (as she is often known) – voted Miss Homophobia 2018 by an LGBT group – said gender-neutral toilets were “for the men who don’t know if they are still allowed to stand or already have to sit down when they pee.”

It might only take another major economic crisis to give them carte blanche to wipe away the rights we have today.

Last October marked 90 years since Black Tuesday. Ask any historian worth his salt for one – and they are only allowed one – reason for the rise of the Nazis and they will talk about this date.

It’s when the Stock Market in New York crashed, heralding the Great Depression. Billions of dollars were lost – in the region of £396bn in today’s money.

Banks went bust, businesses folded. On one particular day (29 October) more than 16,000,000 shares were traded, wiping out thousands of investors.

But there’s a saying about the crash: “New York sneezed, London caught cold and Berlin nearly died of influenza.” German industry collapsed and the unemployment figure of 1.5 million at the end of 1929, rose to six million in the next three years.

And every out-of-work German, who might have taken little notice of Hitler before, became a potential Nazi.

Along with hyper-inflation – one million Deutsche Mark notes were not rare – the scene was set. Hitler promised to make the country great again.

It was nothing short of miraculous that the likes of Oskar Schindler swam against the tide and rejected hate. For saving some 1,100 Jews, he was rightly named Righteous Among the Nations by the State of Israel, an honour bestowed on non-Jews who saved Jewish lives in those nightmare years, and has a tree planted in his name at Yad Vashem, the country’s official memorial to victims of the Holocaust.

By the time the film of his heroics was completed, more than 6,000 people were alive because of him. Bravery – and the effects of such courage – doesn’t come much greater than this.

Schindler and others who saved lives should never be forgotten or have their actions questioned and the fact that they didn’t set out to save gay men in no way detracts from their heroics.

But the fact remains that there seems to be no record of anyone standing up for gay men in the same way. You could say that one of the reasons for that is that given the very nature of gay men, there wouldn’t be many descendants alive today if a gay man had been saved. But who knows what died along with those gay men: magnificent music, maybe. Moving poetry, world-class paintings, the cure for multiple sclerosis or dementia or just the common cold? We will never know.

If you take anything away from all this, maybe it should be two quotes. The first comes from the 1995 book Hidden Holocaust, written by Gunter Grau and translated by Patrick Camiller: “They were all victims whether interned in a concentration camp, imprisoned by a court or spared actual persecution. For ultimately, the Nazi system curtailed the life opportunities of each and every homosexual man…”

And the second is one for the future and comes from one of the greatest Holocaust scholars alive today, Yehuda Bauer, who may have been speaking about the murder of six million Jews, but whose words should ring true for us all.

“Three commandments have emerged from the shadow of the Holocaust,” he said. “Thou shalt not be a perpetrator, thou shalt not be a victim and thou shalt not be a bystander.”