Meeting Iraq’s only out gay LGBT+ activist

This interview was first published in Attitude issue 273, August 2016.

Ashour is an anomaly, though. That he no longer lives in, or is allowed back into, his homeland is indicative of that.

The situation for LGBT+ Iraqis is bleak; a 2015 UN report highlighted the numerous human rights abuses that have taken place there. Put simply, living openly as an LGBT+ person is literally a matter of life and death. Local militias and government agents have a history of targeting queer people, and despite homosexuality not technically being illegal, religious extremists have carried out numerous public executions in recent years.

Parents turning against their children — often kicking them out of the family home — is still an all-too-common response to discovering the youngster’s sexual or gender identity. The climate is one of tremendous fear for Iraq’s LGBT+ community, so most queer people remain very much in the closet.

“A lot of people keep that aspect of who they are as a secret,” says Ashour. “It could lead to losing the opportunity of continuing your education if you are in school. It will definitely lead to losing your job if you are working. In extreme cases it could actually mean being killed, either by extended family members or by religious militias.”

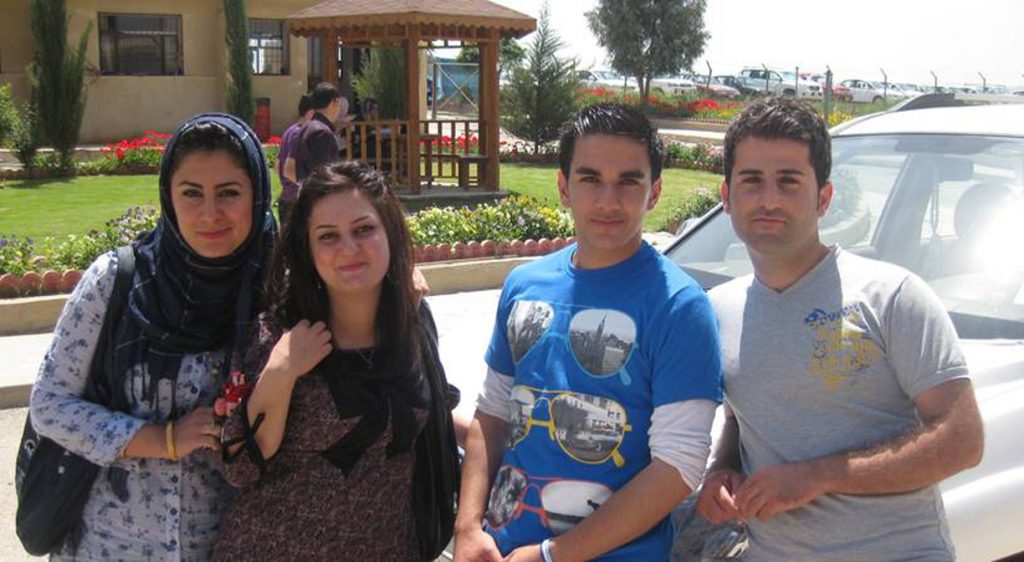

Born and raised in Baghdad, Ashour and his family moved to Sulaymaniyah, a city in Iraqi Kurdistan, when he was 11. In 2013, after finishing his degree in agriculture, animal/livestock husbandry and production, he became the Iraq human rights consultant at Madre, an international women’s human rights organisation, and joined OutRight Action International, an LGBTIQ organisation.

He also began his work in the field of LGBT+ equality, giving talks about gender identity, interviewing queer Iraqis about their experiences and using his contacts to support the most vulnerable.

But he soon became frustrated at only being able to react to the abuses, rather than prevent them, and endeavoured to create IraQueer — Iraq’s first organisation tasked with the proactive emancipation of LGBT+ people.

Co-ordinating such a movement was impeded by Iraq’s queer community being so hidden from the public eye, and finding willing participants requires Ashour, now 25, to expose himself to a potential backlash. Even the underground gay scene that once existed in Iraq was systematically shut down by heavy government policing and the vigilante actions of the local militia.

“There used to be some kind of scene underground, especially in Baghdad, but now the biggest gathering could be about five people, who [already] know each other,” says Ashour. “The people who look more LGBT+ face being attacked in the street by other people, the religious militias or the police.”

Apps such as Grindr and Tinder provide some of the only secure channels of communication for LGBT+ people across the region; they became invaluable tools for Ashour when he started canvassing support for his organisation.

“Because of my work before IraQueer, a lot of people were contacting me and asking what we can do to show support [for LGBT+ rights],” he continues. “I started contacting those people back and I asked them if they would be interested in joining something like IraQueer. I used social media. I used personal contacts, I even used Grindr and Tinder. Out of the many people I contacted, three said yes.”

Despite the poor response, it was still enough to form IraQueer. Together with the contacts he had made at other human rights organisations, Ashour and his team of activists began championing LGBT+ equality across the country. While continuing his work providing safe houses to those kicked out of their homes and arranging medical support for queer people who had been refused it in public hospitals and surgeries, Ashour was now able to engage in proactive tactics.

With the IraQueer website up and running, he and his steadily growing community of activists were able to use social media to disseminate information about the LGBT+ cause, raising the visibility of queer issues and sparking discussions online. He also took the brave step of hosting human rights and gender-identity training sessions, designed to educate people face-to-face. It was a move that eventually saw him arrested — accused of promoting prostitution.

“I discovered that we were monitored by the police; it was very risky to work there,” he says. “They thought I was recruiting people to start brothels and promote sex work.”

And some reactions within the training sessions were also shocking, “In one we were giving to female journalists in Iraq, two of them were very aggressive, saying things such as, ‘why would gay men not like being raped? Isn’t that what they do in the first place?’.”

While the reactions to his sessions were predominantly negative, there were isolated cases which he felt justified the work that he was doing.

“One of the participants was a 55-year-old woman,” says Ashour. “A widow and a grandmother. After the training, she said, ‘I think I’m queer’. I said ‘OK’. And she’s like, ‘what do you mean OK?’ I replied, ‘you know yourself better, I’m happy’. It was as if she was waiting to be judged. We walked for a few minutes in silence. The she said, ‘now I know why it didn’t work out with my husband’.”

As well attracting police scrutiny, Ashour’s training sessions garnered the attention of his close friends, leading to his first arrest. “They took me in the car for a while and asked me to admit that I created multiple Facebook profiles, pretending to be girls, to seduce them to be gay,” recalls Ashour.

“They pushed me and that’s when I called the police. After the police questioned me and them, they came to the conclusion that I was running brothels. That was the first time I ended up in jail.”

After speaking at an international youth conference in October 2014, he was arrested again, this time by Kurdish special forces. After 15 hours of questioning, he was released — and fled the country. He hasn’t been back.

After a trip which took him through Lebanon and Turkey, Ashour settled in Sweden. He is now barred from Iraq but has still managed to build IraQueer’s membership to 40 people, although none of them have met face-to-face and he remains the only one public about his role. It’s not surprising, given that simply posting a “like” can prove costly.

“We will be meeting in person soon, somewhere outside Iraq,” Ashour says. “We use safe ways to communicate. I make sure that all the publications that we post on the website or social media are being done from Sweden, so if something is tracked, it only leads back to Sweden. One of our members was outed by his family because they saw that he was visiting the page and communicating with us.”

While many activists and supporters of Ashour’s work remain anonymous, one advocate is unashamedly open about her unconditional support.

“The first question my mum asked me was, ‘but didn’t you say you want an outdoor wedding?’,” says Ashour, recalling the initial conversation they had about his sexuality.

Visa complications have meant she has been unable to see Ashour since he left Iraq but that hasn’t stopped her following his work with all the unyielding enthusiasm one would expect from a mother.

“I have a very good relationship with my mum; I always have done,” he says. “We talk every day and she always asks about the organisation and if we have grown in number. Every time I have a conference she calls before and then afterwards, to see how I did. She asks me to send her articles in Swedish — which even I can’t read.”

Despite everything he has experienced in his home country, Ashour finds it easy to stay positive. His relationship with his mother, the successes and growth he’s experienced with IraQueer and the messages of support he’s received — locally and internationally —all contribute to his belief that things are getting better, and will continue to do so.

“The situation in Iraq is chaotic at this moment and we see that as an opportunity,” he says. “People are tired and fed up, and are in desperate need of change.

“We might not be able to fully put the LGBT+ issues on the table but we are hoping to increase the visibility of the cause and we see this as an opportunity to promote the Iraq that we want — a place where everyone can find themselves and can feel safe regardless of whether all the aspects of their identities are socially accepted or not.”

His desire to return and continue his work on the ground is overwhelming. But while his initial goal is simply to secure a reunion with his family and carry on working with IraQueer from within Iraq, his long-term goals are much more ambitious.

“I don’t have a timeline for when I can go; I could find out in 30 minutes and I’ll be on the next flight back,” says Ashour. “Or I could find out in five years, but my ultimate goal is to be involved in politics in Iraq. For that to happen I have to be there.

“Some years ago we were afraid of even talking about it, but I want to be able to run for prime minister openly. I will run as many times as possible until it’s done. It’s not only about winning — every time I can run I send a message to myself that this is possible.”

Words by – Chris Godfrey

Photography – Luxxxer