‘We can now live well with HIV, but we also should be able to die well with it – we need to talk about end-of-life care’

"For those of us who confronted our mortality in the 1980s and 90s, we must now do so again. This time, not because of HIV, but due to age," writes Richard Jeneway ahead of a new project with Marie Curie and Terrence Higgins Trust

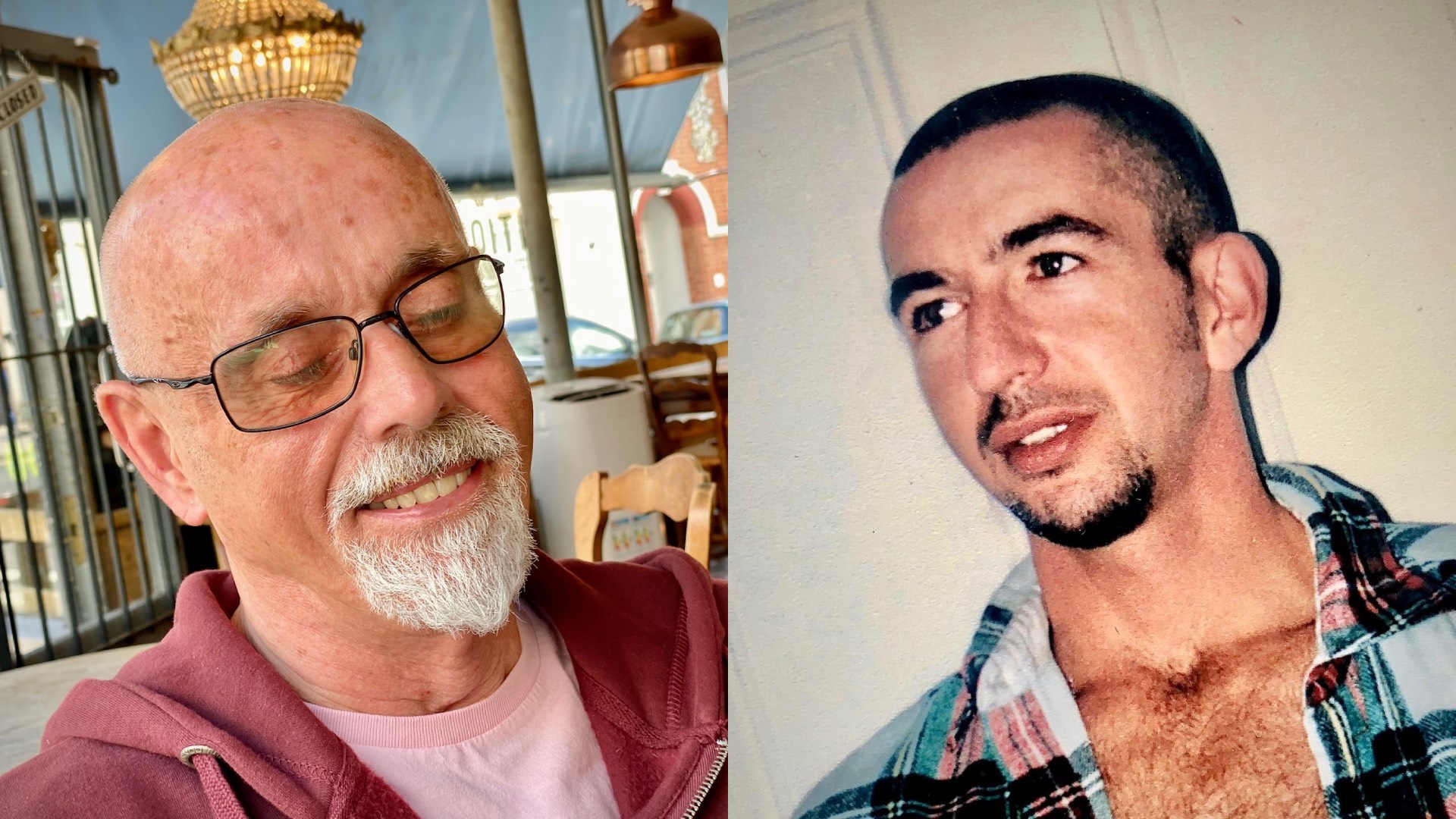

In 1999, my partner of 12 years died from an AIDS-related illness. His name was David. Welsh and very handsome (which he knew far too well), he loved rubber parties and gardening and had the most beautiful blue eyes.

For a time, he had been my carer as well as my boyfriend. I had been very ill because of conditions caused by HIV: pneumonia in my lungs, cytomegalovirus in my eyes, lesions on my brain.

I had been told to put my affairs in order. He took me home from the hospital, changed the drip in my arm and did everything else needed to nurse me.

But then I got better and he got sicker. He never wanted to acknowledge that he might die or talk about what he wanted at the end. He was admitted to the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, and for weeks I slept by his bedside so I could be by him, even when he wanted me to go. The care he received from the staff was compassionate and kind (a contrast with other healthcare settings where staff had been quite ignorant around HIV). But I know it’s not how he would have wanted to go. He even asked me to take his life near the end, and was very angry with me when I said I couldn’t. It was tragic, painful and he was far too young.

I remember being very angry with him after his death because I had thought for so long that I was meant to die and he was meant to live.

I still have his ashes with me.

But it’s been more than 25 years since David died, and I did not. I fell in love again and have been with my partner, Tony, for over two decades, through many ups and downs, including the loss of my sight. But I’m telling you about David because I have been thinking about how I would like to die recently and what has changed for people living with HIV at the end of our lives.

I’ve been helping lead a project with Marie Curie and Terrence Higgins Trust around end-of-life care for people living with HIV, and the report produced as a result is out now.

As part of the project, a group of us living with HIV talked about what we would like at the end of our lives, making art together when words failed, as they often did. It was an extremely emotional experience.

When there was no effective treatment, HIV care was about managing death. Terrence Higgins Trust was founded to fight for better treatment and to support people in their final days – many of them tragically young. That’s something that David and I experienced firsthand.

But thanks to incredible advances in treatment, the population of people living with HIV is ageing – over half of the people in the UK living with HIV are now over 50.

The very virus to which so many of us have lost partners, friends, loved ones far too young, is one we now hope to live with well into old age.

But for those of us who confronted our mortality in the 1980s and 90s, we must now do so again. This time, not because of HIV, but due to age.

“Over 40% of participants in the research said their HIV status had negatively affected their care when visiting a GP”

I was struck by how many people in the workshops were worried about the stigma they might face as people living with HIV in end-of-life care, shaped by previous negative experiences they had with healthcare, even decades earlier.

Stigma around HIV persists. Over 40% of participants in the research said their HIV status had negatively affected their care when visiting a GP, hospital or dentist. Too many people, including medical professionals, are unaware that those on HIV treatment cannot pass on the virus to others, or even that it’s never been possible to get HIV through saliva or touch.

This new report will bring greater attention to the concerns of people living with HIV around end-of-life care, which will help hospices take positive action.

But I hope it also helps more of us to think about what we want from the end of our lives.

For LGBT+ people living with HIV, the report highlights how many are worried about holding onto their identity in an environment where straightness might be assumed. It’s something I often think about. For one person in the workshops, having his music and a bottle of poppers were key things he wanted to have to still feel connected to his sexuality. All of us should think about what things we would want to connect us to our identities.

Whether you are living with HIV or not, whether you are old or not, start thinking and having conversations with those close to you about what you would like to happen at the end of your life.

I have made arrangements that if I get dementia or a similar illness, I will be cared for in a home. It’s important to me that my partner, Tony, can carry on with his life, as hard as that may be. And if I have a terminal diagnosis, I would like to die at home if possible or in a hospice if not.

After my death, I have asked that my ashes be put with David’s.

What is right for you will, I’m sure, look very different. But it’s important that each of us consider what we want whilst we can.

As people living with HIV, we deserve a good life. But when the time comes, we also deserve a good death.

Marie Curie’s information and support line is available for anyone with any questions about dying, death, bereavement and terminal illness. Call free on 0800 090 2309 or visit mariecurie.org.uk/help/support.