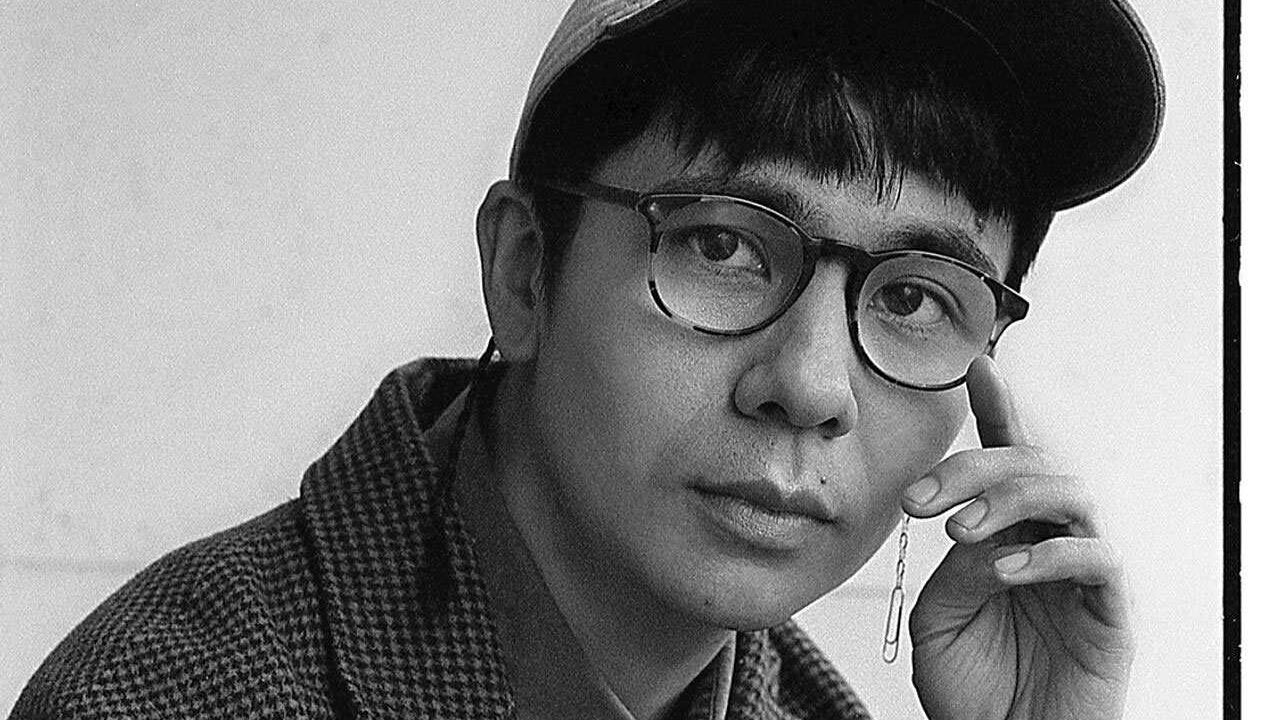

Ocean Vuong on smalltown queer life, Studio Ghibli’s influence, and why ‘even fiction is an artful lie’ (EXCLUSIVE)

In association with Audible

By James Hodge

Renowned writer Ocean Vuong has a rare talent: not only is he a celebrated poet but a bestselling author too. His first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, was autofictional excellence that became an international hit and truly established his artistic manifesto.

Now he returns with The Emperor of Gladness, charting the life of second-generation Vietnamese immigrant, Hai. After a lie to his mother nearly leads to him taking his life, Hai begins again in a forgotten small town.

The novel is full of heart and humour, charting the way queer people must deceive themselves and others through the stories they tell in order to survive.

During a book tour to London, Vuong spoke to Attitude about how Studio Ghibli movies inspire his writing, and the power of circumstantial family.

We also share our picks of the best recent reads, as well as our current favourite audiobook available on Audible.

You began your writing career as a poet. What inspired you to make the move to novels?

I’ve never been beholden to the idea of being a poet. As a queer person, I never believed in these literary borders. Being a poet is a tendency. You slip between forms. Switching lanes was inevitable. As Ann Carson says, “The only thing I promise myself is not to be bored.” I didn’t want to stay in one genre too long and become bored of myself.

What was the biggest challenge of novel-writing?

Being OK with writing utilitarian sentences: “He stepped into the room, pulled out a chair, and sat down.” I couldn’t bear those to begin with. They were not my words; they come from culture. ChatGPT can write them. But in a novel, you do need these to situate your characters.

Explain the title The Emperor of Gladness.

American places have very hyperbolic names: Alliance, Defiance, Corpus Christie. In the novel, I explain that Gladness no longer exists. To be the Emperor of Gladness is to be the emperor of nothing. An emperor is a ruler — powerful, capacious. So the title is deceptive, echoing the novel’s theme of deception.

The novel is about the lies we tell others, but also the lies we tell ourselves. Where did this sentiment come from?

Lying is the ultimate taboo in America, right? That’s kind of the ethos. In reality, American politicians perform honesty, but in fact everything is about deception. And the American working people have nothing to give one another but stories. Stories are, in themselves, lies — whether benevolent, creative, humorous. Retellings. Even fiction is an artful lie. We punish those who lie in our personal lives, but our politicians lie without consequence daily. I wanted to explore that dichotomy and double standard.

One character, Grazina, suffers from Alzheimer’s — a condition in which she believes the lies her own brain tells her. What was the process like writing her?

I was in a computer science class and had a choice of projects: to make a programme out of HTML (God help me!), or volunteer at a nursing home helping senior citizens use a computer. I worked very closely with these folks and it was an eye-opening experience. Equally, I grew up in a house with a schizophrenic grandmother. I never tell the stories of real-life people, but I borrow from them. So this is my fictive take on those people and their stories.

There’s a trend in contemporary fiction to explore smalltown queer life. What made you want to tell that story?

I grew up in a town of 30,000 people working on tobacco farms. Queer rurality is important to me because all the films and TV shows I watched told me that the only happy ending would be in the city. But what about those of us who don’t have the capability to escape, because of money or family ties? Some of us just cannot get out. What is queer life if you can’t get out? It’s a struggle and from that struggle comes incredible stories.

Much of the novel charts life working in a fast-food diner. What does the American diner mean to you?

My mother and I lived in government-funded tenement housing. If your family income increased after a certain threshold, you would be kicked out. The economic reality was that the home became a cage. Talk about the American dream. If we made over a threshold, we would be kicked out and have to rent on the free market. We couldn’t afford that: we would be homeless. My mother sat me down and told me, “You have to work a minimum wage job — get a job at a fast-food restaurant.” A young child told “Don’t dream. Don’t ask for more.” So I worked in two over three years. This is that story.

The heart of the novel lies in the friendships Hai makes in the diner…

As queer people, we talk a lot about chosen family. Here, they are a circumstantial family. My experience is that when you’re in a room of people working towards a common goal, regardless of differences, love happens. I have worked in rooms where people believed I would burn in hell because of my sexuality. But slowly, working together, beliefs degrade and become inconsequential to the relationships at hand. To me, that is a beautiful thing.

The novel begins grounded in realism but ends in, almost, the fantastical. What shaped that?

I was inspired by Studio Ghibli’s co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. They have a charming, soft, cute aesthetic but talk about big issues: war, ecological decline, existential crises. If On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous — my first novel — was very serious as an artist’s statement, I wanted to challenge myself to write something exploring the real troubles of pastoral America with levity and humour and quirkiness.

As a Vietnamese man who grew up in America, what are your feelings about the current discussions around immigration?

My message is not anything radical or new. Simply that the idea of an origin of a pure people of any country or race is a fantasy. We police it to our own demise. Who gives you healthcare, repairs your house and farms your food? Immigrants! It’s the storytelling that has got us into the trouble we are now in. In the words of Shakespeare, it’s “much ado about nothing”. The government should be focusing on making social change, rather than defending an outdated fantasy.

What is the poem that everyone should read?

Tours by C.D. Wright. A masterclass in synaesthesia through light, precise strokes of sound and image.

A poem you know by heart?

[Ocean proceeds to recite The Red Wheelbarrow by William Carlos Williams.]

Your favourite international writer?

Arthur Rimbaud. Illuminations was my first portal into poetry.

A story that helped you write Emperor of Gladness?

D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers — a powerful portrait of a coal-mining family, a gay boy and his mother.

Name a queer novel that changed your life.

Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood — formally radical, bizarre and liberating. It remains a book that gives permission to do anything.

If you were to have lunch at HomeMarket from The Emperor of Gladness, what would you read?

Moby-Dick by Herman Melville — I would want to escape on the Pequod.

A book with a quest narrative you enjoyed?

Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing — a flat, existential journey where the growth is entirely internal.

An author on the rise you’d like to promote

Mieko Carson, The Laughing Barrel. Inspired by the story of enslaved people laughing into barrels, it’s a searing, powerful collection.

Recommended Reads

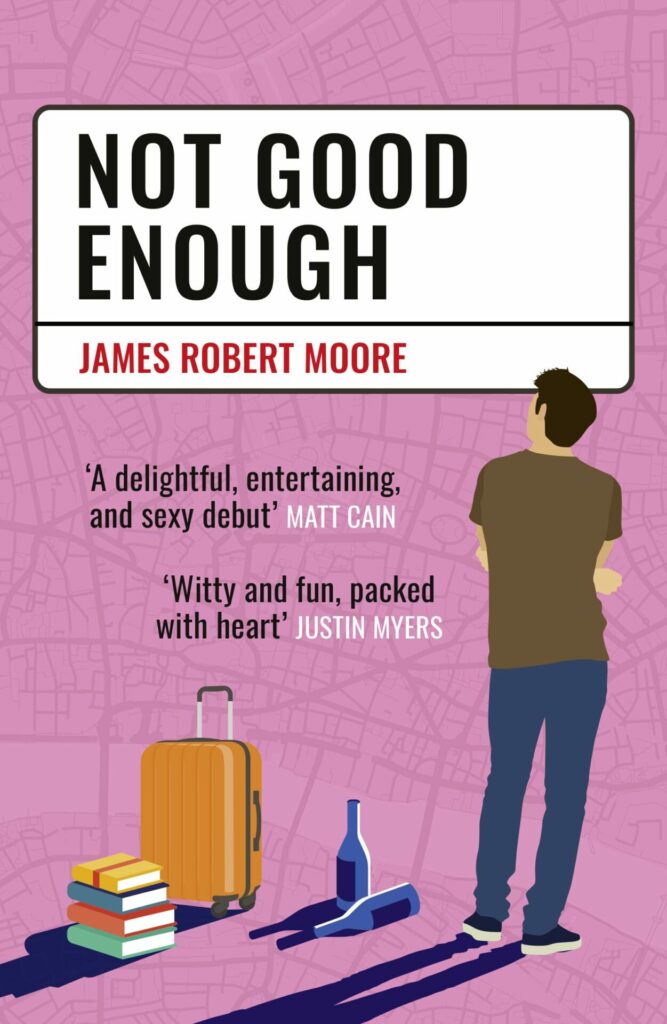

Not Good Enough by James Robert Moore (out now in paperback)

Sometimes it can be hard to categorise a brilliant book. Moore’s debut novel sees late-twenties Charlie newly single after the sudden breakdown of a long-term relationship after his boyfriend betrays him. It’s a light and breezy read: charming, laugh out loud and pointed when it comes to its lens on the trials of queer life. Equally, it packs unwitting emotional heft, as our protagonist navigates dating, the apps, and the scene. Perhaps most surprising is its racy retelling of kinky hook-ups. If this is a romcom, it’s about rediscovering the love of the self — and feels like a reinvention of the genre.

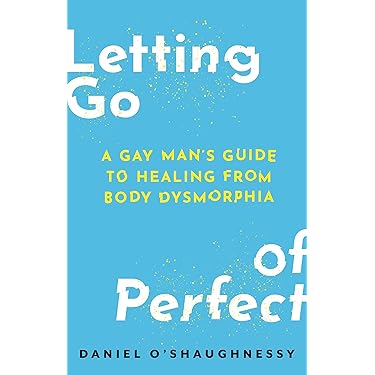

Letting Go Of Perfect by Daniel O’Shaughnessy (out 21 October)

Subtitled as a gay man’s guide to body dysmorphia, this self-help guide begins, unusually, with the deeply personal autobiography of nutritionist O’Shaughnessy. His story is a common one in our community: food struggles, anabolic steroids, and the pressures of gay life. The healing of his own body dysmorphia has led to his producing this book: guidance as to how to heal yourself. Packed with reflective activities and informed by academic insight, life experience and therapeutic approaches, this is a read for anyone who is on their journey towards self acceptance and needs some wise, kind words to help them along.

Audiobook pick

The South by Tash Aw

Read by the brilliant actor and voiceover artist Windson Liong, this Booker-longlisted read explores rural Malaysia from a queer perspective. It tells the tale of Jay, a lost boy whose family inherits farmland after the passing of a grandfather. Jay is an outsider who doesn’t belong either to his family or to the smalltown society he is forced to inhabit. He is struggling to navigate a world designed for the white and the masculine.

The farm is dying, and this is a novel about the duality between regeneration and destruction: Jay’s mother tries to grow within the confines of an unhappy marriage, while his sister branches away from the expectations of tradition. And for Jay, a forbidden love blossoms with farmhand Chuan.

Prosaically simple in its execution, this is a thoughtful novel that reflects on how we can always aspire to begin again despite the obstacles society presents us.

New to Audible? Get a free trial and enjoy bestselling audiobooks, exclusive Originals, and more on the Audible website.