A Night Like This review: not every LGBTQ+ story must seduce

Liam Calvert chooses jaggedness over gloss in his daring debut, setting a story of fleeting tenderness against a cold Christmas London between stars Alexander Lincoln and Jack Brett Anderson

Liam Calvert’s debut A Night Like This offers an altogether different type of connection, one that is uncommon in LGBTQ+ cinema. His interpretation occupies a strange, lonely spacetime: a rush of intimacy in slow mo. A night out in London that becomes a crucible for identity, desire, and alienation.

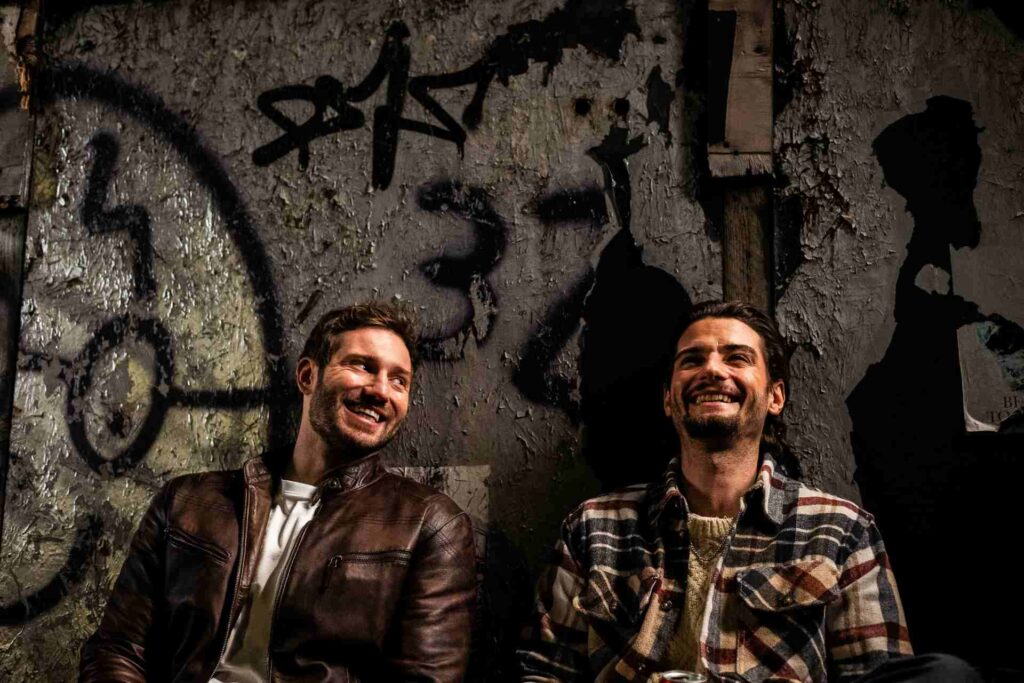

The film follows Oliver (Attitude cover star Alexander Lincoln), a nauseating club owner and aspiring musician, and Lukas (Jack Brett Anderson), an aspiring actor whose precise, almost mechanical speech is as measured as Oliver’s is brash.

Their encounter one winter evening unspools into a pact to stay together until dawn. As a viewer, you spend the night with them both. You drift across pubs and backstreets for cold pints and proclamations, flirtations and confrontations, conversations that oscillate between the trivial and the existential. However, if your true motivation of accompanying them is the hope of witnessing an In From The Side-style sex scene, you’re barking up the wrong wood. Instead, Lincoln and Anderson perform what is often missing in queer narratives: exquisite imperfection.

Shapeshifter Lincoln effortlessly leans into Oliver’s ADHD-inflected bravado, but the irritation dissipates as his vulnerabilities bubble to the surface. Anderson, in contrast, plays Lukas with quiet restraint and despair, his wary eyes hit deeper reserves. There are moments that are constructed to linger. The eventual tickling and jostling between Oliver and Lukas, the kiss on the dancefloor of the silent disco does deliver gay dopamine, but by no means does it define this film.

Calvert’s choice to set the story at Christmas is pointed. This is not a London that warms the cockles. There is no Love Actually montage punctuated by the glistening windows of Selfridges. It is instead the discomfort of a sweaty top deck of a night bus. London rendered as a void: a metronome to serve the protagonists in performing an adagio of rapport, punctuated by sparks and embers of intimacy substituting the dizzying lights of Oxford Street.

The film’s dialogue deliberately spells out its themes- selfhood, mental health, queer identity. The wordiness can grate, but it is ultimately a device that reflects the urgency of connection of both characters, against the ticking clock that threatens to cut them off come dawn. At times, characters over-articulate what might have been more powerful as silence, but this viewer can sympathise with the over-flapping of gums to retain company in the hope of striking deeper. There is something honest in this portrayal.

Calvert’s mood is permeated by the question of what truly sustains Oliver and Lukas’ pact to stay together. It is perhaps more about surrendering to the cosmos rather than attraction: a desire to map profound questions onto an ordinary night. It is an entirely timely endeavour amidst the backdrop of this supposed “island of strangers.”

Calvert’s film is not careless. Far from it. The imperfections feel deliberate, stitched into its DNA. This is a filmmaker obsessed with mood, choosing jaggedness over gloss, awkwardness over ease. Where many debuts might smooth out rough edges in fear of alienating, A Night Like This embraces them, gambling that intimacy can flourish in disorder. That gamble doesn’t always pay off – the narrative spine can feel engineered, the pacing more arduous than lyrical – but there is thought and bravery in the construction.

And perhaps bravery is the point. In a landscape where LGBTQ+ cinema still often finds itself in the realm of ‘does-what-it-says-on-the-tin’ and streaming-friendly, A Night Like This insists on a different cadence. Within a void, Calvert maps a fleeting tenderness: the possibility of an improbable connection, even if it seems doomed to dissolve at dawn. Ultimately, this is a film more resonant in moment than in mosaic. It is a bold reminder: not every LGBTQ+ story must seduce. Sometimes it is enough to absorb the mood, discard the labels, and be reminded that connection is worth the chase, especially if the backdrop is looking grim.

A Night Like This opens in UK cinemas on Friday 26 September