Midlife and the parasocial phenomenon: What I’ve learned about growing older in the algorithm age

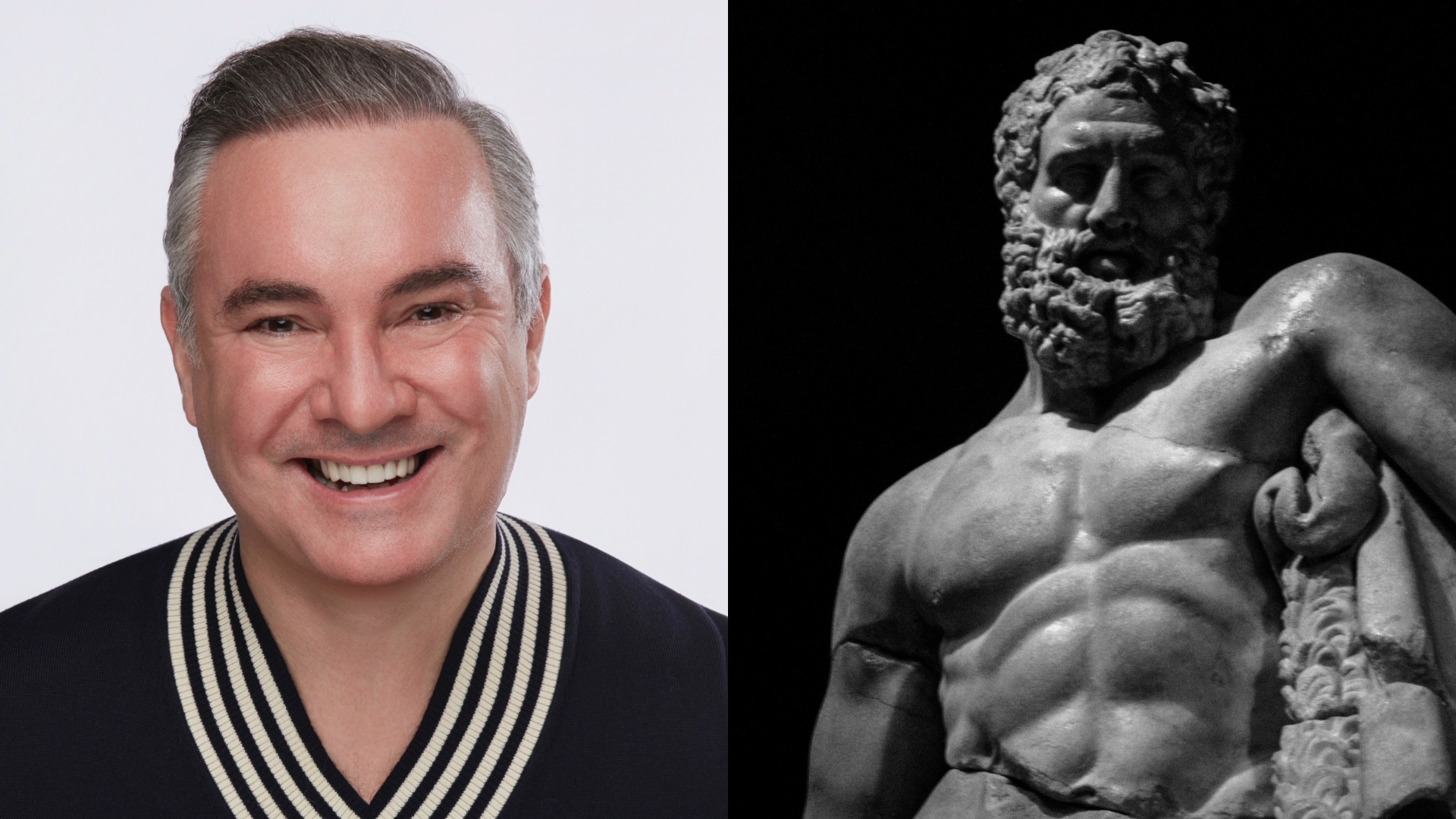

Nick Ede: "Midlife doesn’t need more pressure - and ageing well, it turns out, isn’t about keeping up with anyone else"

By Nick Ede

As a gay man who has reached midlife, I never thought that it would be so difficult to let go of things from the past and look to a different future. I think because we are bombarded constantly with perfection, and queer culture traditionally has idolised this, that the acknowledgement that age is a real thing has come as an almighty shock. And I think I’m probably not the only one.

My social media feed is full of toned torsos and speedo-clad models, who I have obviously liked, and now are haunting me every time I check my devices. This nightmare has caused me to try to decipher how we got here. “Parasocial” was the 2025 Cambridge Dictionary Word of the Year and there is a reason for it.

Parasocial relationships are usually framed as a young person’s problem. A by-product of TikTok and Instagram culture, of influencers and fandoms and over-identification with people who will never know your name. But, from my own personal experience, that framing is both convenient and incomplete. Because parasocial relationships don’t dissolve with age, they evolve. And, in midlife, they take on a different kind of meaning and significance.

Men like Brad Pitt and Mark Wahlberg are not simply ageing well, they are ageing differently

A parasocial relationship, defined simply, is a one-sided emotional connection with a public figure. In practice, it’s the quiet accumulation of images, behaviours and ideals that begin to feel intimate through repetition. Faces that appear daily. Bodies that don’t seem to age at the same pace as our own. Lives that appear ordered, disciplined, controlled and insanely hypnotic.

Being in your fifties now bears little resemblance to being in your fifties a generation ago. Our parents’ midlife was marked by slowing down, stepping back, becoming less visible. Ours is occurring in full view amassing millions of views.

The cultural messaging is clear: 50 is no longer an exit point. It’s a continuation. Men like Brad Pitt and Mark Wahlberg are not simply ageing well, they are ageing differently. More assured and more comfortable in their bodies and, in some ways, more compelling than they were in their youth. Their continued visibility offers something quietly radical: proof that ageing doesn’t have to mean disengagement.

For many men like me, that representation is not oppressive. It’s motivating. Watching men in their sixties remain physically capable, professionally active and culturally relevant reframes what midlife can look like. It suggests maintenance rather than decline.

This is where parasocial relationships become complicated.

The mental health consequences are real. Particularly in midlife, when identity is already under such internal scrutiny

There is no question they can be damaging. They encourage comparison and usually that comparison is with someone 25 years younger, an OnlyFans model or a cast member from Heated Rivalry. Books like The Velvet Rage have long explored our obsession with proximity – the idea that being close to power, beauty or success confers value by association. Social media has turned that proximity into a daily experience. Not access, exactly, but the illusion of it.

Television has mirrored this tension with series like The Beauty imagining a world where appearance becomes a form of power and bodies function as currency. These narratives are intended as warnings, but they resonate because they exaggerate dynamics that already exist.

The mental health consequences are real. Particularly in midlife, when identity is already under such internal scrutiny. Career dynamics shift, bodies rapidly change and your own visibility feels less prevalent or guaranteed. Parasocial culture doesn’t create those anxieties, but it does amplify them.

I’ve written publicly about my own attempts to navigate this terrain with health interventions from hair transplants to nose jobs and supplements galore. Those articles prompted an overwhelming response, not of judgement, but of recognition which I found quite surprising. Men admitting, often privately, that they felt the same pressure, the same awareness that looking after yourself now feels less like vanity and more like upkeep in a good way not a Death Becomes Her way!

Midlife doesn’t need more pressure – and ageing well, it turns out, isn’t about keeping up with anyone else

What’s rarely acknowledged is the paradox at the centre of this. The same parasocial pressures that damaged my mental health also delivered a jolt of motivation. A blunt reminder that neglect has consequences. Since I began taking my health more seriously – exercising consistently, eating better, paying attention, the effects have extended well beyond the physical. I’ve had more energy; more focus and more confidence which when you live with imposter syndrome can be dented constantly.

But midlife is rarely neat and I’m finding that out daily.

It is possible to recognise the harm in parasocial relationships while acknowledging their catalytic effect. To accept that inspiration and pressure often arrive wrapped together and to admit that watching others age well can encourage engagement rather than despair.

Body positivity, at this stage of life, cannot be reduced to acceptance alone. It has to include caring about appearance without being consumed by it.

For men, this marks a quiet shift in how masculinity operates at midlife. Strength is no longer just endurance and looking after yourself isn’t indulgence, it’s maintenance. A decision to stay present rather than fade quietly out of the frame, a decision comes with responsibility. Parasocial relationships work best when they’re kept in proportion. When inspiration doesn’t slip into comparison. The danger isn’t watching others age well it’s measuring yourself against a highlight reel and mistaking it for reality.

The challenge, then, isn’t to reject parasocial culture entirely, but to filter it. To keep what motivates you, discard what diminishes you, and step away from anything that leaves you feeling smaller, slower or less-than.

Midlife doesn’t need more pressure – and ageing well, it turns out, isn’t about keeping up with anyone else. It’s about staying connected to yourself physically, mentally and emotionally long after the algorithm has moved on.

Nick Ede is a public relations, pop culture expert, TV presenter and charity campaigner. He founded the London-based PR agency East of Eden and the Style for Stroke foundation, and has appeared on shows like Good Morning Britain and Project Catwalk, using his platform to raise awareness for stroke and social issues.

Get more from Attitude