Resort 12: The place where kindness is healing addiction

The rehab facility caters for all addictions from drugs, alcohol to the gym

By Will Stroude

This article first appeared in Attitude issue 295, May 2018

Research shows that queer people are more likely to smoke, use alcohol, attempt suicide and suffer mental health problems than their straight counterparts.

As our community continues to probe the reasons why, Cliff Joannou visited Resort 12 – an LGBT rehab facility in Thailand – that aims to help the healing process.

Resort 12 is a 40-minute drive from the northern city of Chiang Mai, in Thailand. Located at the foot of the surrounding mountains, a lush green jungle hangs over its thick stone walls and a bamboo fence that must be 12ft high. We approach a guarded gate before we snake around the perimeter to the towering main entrance.

The huts that are visible through the foliage look akin to those in a fancy resort, with their perfectly manicured gardens and man-made lakes.

“From the moment I came through the guard gate, I noticed little things,” Jim, 54, from St Louis, and a client at R12 tells me later that day. “I immediately spotted the barbed wire between the bamboo, and the next gate had to be opened by a fingerprint scanner. It is scary. Then the gate closed behind me. It’s a very subtle prison. But you know you’re in a safe environment. I love not having triggers such as bottles of booze in a restaurant.”

As we talk, the birds chirp and flutter outside. It’s a tranquil environment, peaceful and still. But the calm in the air runs counter to the psychological and emotional turmoil its residents are battling. The majority of people at the “villages” within addiction treatment centre The Cabin are fighting drug and alcohol problems. Some are sex addicts or even hooked on the gym.

I’m escorted through the grounds to R12, the only addiction clinic outside of the USA dedicated to treating LGBT+ people. Everybody at The Cabin shares common facilities such as the gym, but the treatment rooms are separated, with the main distinctions being The Edge, which is for young straight men dealing with anger issues, and R12 — which treats the very specific needs of LGBT+ people.

At R12, I meet Stu Fenton and Sandi James. Stu was a school teacher in Sydney and a former crystal meth and GHB addict. His first experience of rehab was in 2003, age 33, when he spent 11 months getting clean.

Sandi is also from Sydney. “I was from a similar stomping ground to Stu,” she tells me as we sit in one of the therapy rooms at R12. “I was one of the gutter-dwellers. Heroin was my drug, I didn’t really touch anything else and I was on methadone for years.”

Counsellors: Stu and Sandi can draw on their own experiences with drug addiction

The main difference between the experiences of Stu and Sandi and other people here is that they are the counsellors leading the recovery programme. When Stu left rehab he decided he was done with teaching. Inspired by his experience, he changed career direction and trained as a therapist. Since then, he’s worked in his own practice and at hospitals, helping treat gambling, sex addiction, love addiction/avoidance, depression and anxiety.

Sandi has studied extensively and is about to embark on her second Masters degree in applied science psychology. She previously worked in the mental-health sector with Aboriginal people (both adolescents and adults), and people with severe behavioural disorders or alcoholism. She has also worked with the trans community and people with gender-identity confusion.

The two of them have only worked together for a matter of weeks and their personalities appear quite different, but there’s a clear synergy between them. I joke that they come across like a married couple, at which Stu smiles. “It really is like that, which kind of feels nice in a way because a lot of the relational stuff that drives people towards an addiction comes from the family of origin.

“If I had to put it in a nutshell, in a way Sandi and I are trying to be functional mum and functional dad,” he adds.

“He’s the mum,” Sandi chimes in, grinning.

The lack of healthy adult role models in the lives of many young LGBT+ people is a contributing factor to the problems that Stu and Sandi encounter. While there may be more LGBT+ faces in the public eye today, historically visibility has been lacking. For most gay men, the tangible examples of other gay people they meet are often those in bars and clubs, or via hook-up apps.

“My role models were drug and steroid-taking guys who loved to go to Mardi Gras and get shitfaced,” recalls Stu. “I never had a strong gay man to look up to, one who had boundaries and a healthy self-esteem. That’s one of the reasons I want to be here; I have been through the mill of taking every drug in the world, doing sex work, contracting HIV. Pretty much anything that can happen to a gay man has happened to me, so I’m able to bring that into the discussion here.”

At R12, they look to break down the barriers of disclosure. “Like hep C,” says Sandi. “We talk openly about some of the injuries that occur from certain sexual behaviours, so people can talk about bleeding or whatever.”

What is especially powerful is the level of care and support among those seeking treatment. “One person was able to release all kinds of shame, guilt and terror; everything that had been banked up for so long,” Stu says about a session in which a client shared their sexual history. “Some of the group said ‘I identify’, and the rest said, ‘I think you’re so brave for sharing that with us, it’s so powerful that you’re willing to take this risk to heal’. It was incredibly healing for that person.”

He continues, “By the end of that process no one said, ‘I think you’re disgusting’, which is what happened to me in rehab when I disclosed my HIV status. A guy stormed out of the room.”

Hitting rock bottom

I spent three days at Resort 12 joining group discussions, hearing individual stories and meeting with the counsellors to learn about the kind of work they are doing to tackle the issues behind addiction. The people I met come from all over the world. Mike, 34, from Slough, launched his own music agency at the age of 28. “I remember leaving the record label and I had all these bands that wanted to come with me, so my ego was up there. I was earning good money and that first weekend freelancing, I picked up the crystal pipe,” he tells me, having just completed 28 days at R12. “It was sustainable at the beginning but by the third or fourth year I was not turning up for meetings, calling in sick… nothing mattered: not friends, not family or work, just the drugs. It was all-consuming.”

He had enjoyed recreational drug use in his twenties without a problem until he discovered crystal meth. “For me, meth had always been a big no-no, like heroin. When I first did it there was intrigue. None of my friends did it, so I kept that part of my life secret for a long time.”

His normal routine would be to go out for a meal or to a club with friends, then leave them, go online, meet a guy and stay up for another two days. What started out once a month, turned into every couple of weeks, then every weekend, and eventually every day. Being his own boss meant Mike didn’t have to answer to anyone, working his addiction around his career. Eventually, chasing a bigger high, he started injecting. “The first time I injected I remember there was a lot of peer pressure. Everyone in the house I was at was doing it and I’d been in that situation before but I was happy not to do it. But with sleep-deprivation, coupled with a bit of intrigue, there was a thought of: ‘fuck it, I’ll try it’. After that first time I was doing it every day for a week with no sleep and no food.”

His rock bottom came four years ago, on Christmas Eve. “When everyone was going home to see their families I cracked on. It was suddenly the day after Boxing Day, I hadn’t been home, I had a really bad psychosis. I called my friend and told them I didn’t know where I was and I needed help because I thought people were following me.”

Two years ago Mike’s business folded and since then he’s spent most of his time unemployed, just doing odd jobs in music and production and surviving on benefits. It’s almost as if he felt he didn’t deserve the success, sabotaging the happiness he created for himself.

Duncan, 29, is from Australia but grew up in Japan and Hong Kong and now works in finance. “It’s stressful in terms of work, the expectations and pressure,” he says. The most shy of the group I meet at R12, he is slow to talk about his experiences but once his confidence kicks in, he’s happy to share. “I drank because I was stressed at the end of a long day. I was like, ‘Do I go to the gym or just meet friends and drink and forget about the stress?’

“In Hong Kong, cocaine is everywhere and at the centre of the gay world and finance world, which is a recipe for disaster if you’re in both.”

Vas, 30, is from Essex. He’s a TV personality and has been in R12 for 1½ weeks when we meet, his substance abuse revolving around drugs and alcohol. “I went too far. Drinking too much, staying out for days. The lifestyle I live and the circuit I’m on [make] it impossible to avoid,” he says.

“My life becoming unmanageable, missing filming and making decisions that I wouldn’t make sober was my rock bottom. The realisation I’d spent the past year drunk was a big one.”

Sean, 26, is from North London and admits that his drug use was entirely down to a desire to escape after a disastrous coming out to his parents, who are from the Caribbean. “I met this guy who was doing MDMA and he invited a friend who was doing crystal meth,” he says. “I was very naïve. I just wanted to feel loved, and took whatever was needed. I thought sex and drugs were my answer.” He connected with people on apps such as Grindr, which also facilitated finding drugs and he dived headfirst into the chemsex scene. “My whole world opened, and I thought that was gay culture. I met lovely people but it was just unfortunate that we were doing bad things. The longest I was partying was a week, a whole week. I missed classes, I missed work.” His life continued on a downward spiral, which resulted in him entering rehab for the first time at R12.

Censoring the gay you

Unlike Sean, this is Mike’s third time in rehab. His previous experiences involved spending 28 days in a facility outside London, and attending another charity-based one in the capital.

Reflecting on his experience at R12, he realises how important it has been to address the gay element in his therapy.

R12 opened its doors last November after being developed by the Cabin Addiction Services Group, to cater to LGBT+ needs.

Duncan was originally seeking treatment in the Cabin before being transferred to Resort 12. “I was there for two days and found I was censoring myself. We’d be talking about trauma or upbringings, and I didn’t actually say I had a hard time in school dealing with the insecurity of being gay. I guess the nervousness is still there,” he reveals.

Mike highlights how the gay community uses drugs differently, notably through chemsex. “It’s moved away from the dancefloor into a room with the curtains closed. It’s gone underground. To be in a room full of other gay men talking about trauma, childhood experiences, is invaluable.

“In other rehabs you don’t realise you’re censoring yourself at all. You think you’re being totally honest — and you are to a point, telling stuff you’ve never told people before, about injecting and using — but you leave out all the sexual stuff which is a massive part of my addiction, because you are worried about being judged and that people don’t want to hear about certain websites, talking about unprotected sex, or just men having sex with each other. It was a massive difference, and freeing to walk into a room to talk openly.”

During the deepest times of his addiction, Mike missed a friend’s wedding and major work events, turning his phone off while he was high. When his business folded it fed the shame around his actions.

Stu agrees that shame and the fear of being judged are big blockers to the lasting progress people want to make.

“I think most gay people grow up in homophobic families, homophobic societies, getting called faggot on the street. Growing up in Sydney, that was my experience repeatedly,” he says. “There’s a lot of carried shame, it’s not our own shame, it’s shame given to us by society and our families.”

When a person comes into the safe environment of R12, they start to drop their barriers, often for the first time, speaking in a more confident way about their sexuality.

It’s easy to look at how progressive countries in the West are now in terms of LGBT+ rights, but these advances are only recent. Society moves at a much slower pace and even young people like Sean have to confront older parents who refuse to see homosexuality in a positive light.

The recent referendums on gay marriage in Australia and Ireland are talked about in one group session, but, as Stu highlights, these also work as subliminal indicators of society’s disapproval: while 62 per cent of people voted in favour of equal marriage in Australia, 38 per cent were against. Which other group in society has to witness the disapproval of its existence from two in every five members of the wider population? The issue of subtle homophobia is often raised at sessions at R12, during one-to-one counselling and group discussions, which also touch on subjects as diverse as bottom-shaming, bisexuality and childhood bullying.

Duncan agrees that there is still much internalised homophobia carried around by gay men. “There’s a lot of self-acceptance that needs to happen. I’ve realised that I drink and do cocaine because I want to fit in,” he says.

One of the youngest in R12, Duncan came out when he was 23. While his liberal parents accepted his sexuality, he still hadn’t come to terms with it himself and spent the past 18 months in straight clubs. In hindsight, he thinks maybe he was escaping the reality of his sexuality. “You walk into a gay club and you feel that people are assessing you, how you walk, how you act, and that can be uncomfortable.”

Sex vs intimacy

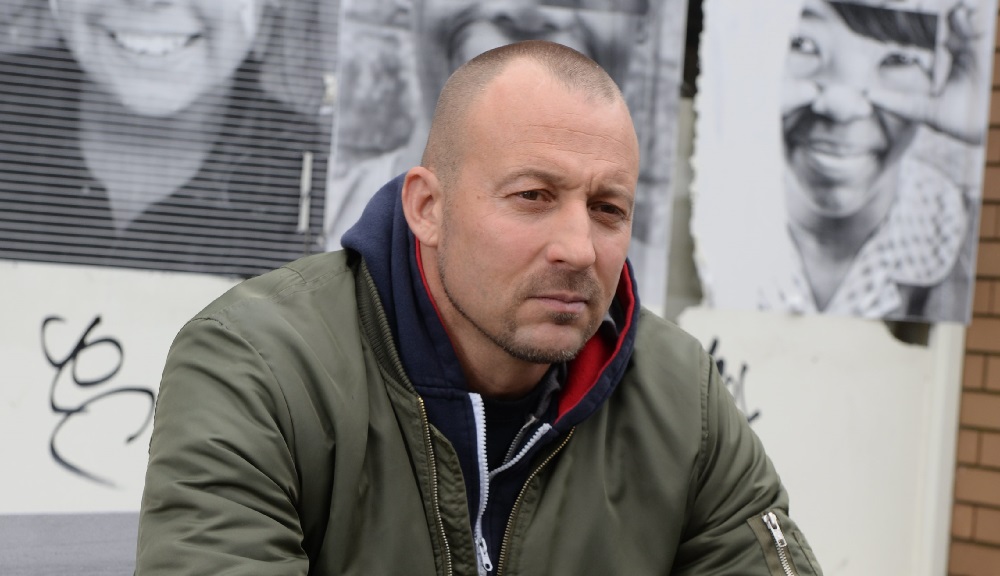

Mike: “Over a certain amount of time, the drugs can become destructive”

Gay men saw homosexuality go from being illegal in the 1960s to the sexual liberation of the 1970s, equating it to death in the 1980s, and fighting for the recognition of our relationships in the Noughties. It’s no wonder we have a troubled relationship with sex and intimacy.

Repeatedly absorbing homophobic messages that our sexuality is wrong, leads many to drugs and alcohol to relax inhibitions around sex. Of course, straight people have sex under the influence, too. But as gay men tend to have easier access to multiple partners, and the fact that our self-worth is often damaged from a subtly homophobic society, putting drugs and alcohol into that mix can be a recipe for disaster.

Vas agrees. “I can’t think of a time when I’ve had sex sober, maybe once or twice in my life. I’m not that hyper-sexual in general, until I’m drunk when it flips the other way.”

Mike understands why some gay men use drugs for sex. “Growing up with an inbuilt gay shame, to discover a sudden sexual liberation can be really freeing,” he says, bluntly adding that he took crystal meth during sex. “But over a certain amount of time, the drugs can become destructive. It’s not intimate, it’s more animalistic and really uncaring and it just gets messy.”

Daniel, 52, a marina developer in Indonesia, is originally from Sydney. He started recovery 20 years ago and has been sober most of the time but has relapsed twice. When he was in Miami, he discovered crystal meth and the intoxicating high it gives when used during sex. “I engaged with situations I wouldn’t normally for 15-hour sessions. It’s a vicious drug. It usually starts with me saying, ‘let me try this’, and ends in the same place: a small room. Your life just gets small and sadder. The disease is in me, it’s not in the bottle. That’s my reality. ‘Fear of intimacy’ goes in headlines when I think about it.”

Amanda is also from Sydney and has spent the past 17 years on crystal meth, the last 10 of which saw her using it daily. For her, sex and drugs are interlinked in a more devastating way. She was of sexually abused at the age of six, and raped by a friend of her brother when she was 14. Her stay at R12 has been one of the first times she has spoken about those experiences openly. Not even her best friend knows. “If I hadn’t been here, I think I would have died with the secret,” she says.

Sean was also raped — during a chemsex session involving crystal meth. In another session, a person gave Sean an overdose of GHB and injected him with meth. He contracted hep C. After seeking medical help he was referred to London Friend and Antidote’s service, which helped him start his recovery and led him to R12.

Sexual attraction to the same gender is what differentiates gay people from the wider population, and we are too often vilified for a desire that is perfectly natural. Our sexuality is a source of pleasure but can also bring conflict when parents or friends shun us. It creates a fractious relationship between our desire to be loved and our desire to enjoy our bodies. When drugs and alcohol get in the way of genuine intimacy, it becomes a challenge to open ourselves up to loving others — and ourselves.

Coming out never stops

Coming out stories are central to our community’s journey to self-love. They vary from the common scenario of a sympathetic parent raising an eyebrow and subtly whispering “I know” to their kid, to awful situations where children are thrown out of their home. In one of the group sessions I join, we talk about the importance of LGBT+ people sharing these stories. We discuss how most of us never stop coming out — be it to new co-workers, neighbours, your GP, or the receptionist at a hotel. But how do you confidently come out to a stranger without fear of judgment if your first experience was a disastrous one?

A negative coming out experience was a major factor that pushed Sean towards addiction. His mother didn’t accept his sexuality particularly well and that night he sought drugs for the first time.

Vas, meanwhile, doesn’t believe he actually had a coming out moment. “I feel as if everyone knew before I did,” he tells the group. “I didn’t realise what was behind my behaviour until coming here. I’d never immersed myself in a gay environment. Most of my friends are girls or straight guys, and a lot of that has to do with internalised homophobia. I felt safer in a straight environment. Coming here has taught me to accept myself. Hearing other people’s coming out stories has been inspirational because I never would have heard those in a straight environment.”

Jim, who is having treatment for addiction to alcohol, was thrown out of his home for being gay by his mother. “She was a strict Roman Catholic. She was like, ‘you’re sick, see a doctor, get cured’. She says she didn’t throw me out, she gave me a choice: get cured or get out,” he says.

Jim went to live with his dad in Los Angeles. When he heard what happened, his dad came out to him. “I suspected before, there were signs. On a superficial level we connected, going to gay bars together. He even hooked me up with a guy one night at a country-and-western bar. It was fun but it didn’t improve our bond. He abandoned us as kids. He was out of there once they divorced, and didn’t pay child support.”

By the time Mike came out, at the age of 15, he had endured years of bullying from his older brothers. Although this may not have been intentionally vicious, he realises now that it had the effect of making him hide his identity for the previous seven years. “I’d walk into a room on a daily basis and be called ‘you gay, you queen’. I just thought that’s what happens. It was years of systematic bullying and it drove me underground,” he says reflectively, clearly still processing the emotions and revelations he’s experienced during his time at R12. “During that time I went really quiet, watching what I said and how I said it, playing football to hide it when the reality was I was the more creative one.

“I’ve since learned to understand why I was being so secretive with my adult behaviour and the drugs.”

Mike’s most challenging times at R12 were the one-onone sessions with Stu, during which he would “talk” to his younger self at the age when his trauma started to happen. “You work out your own way to repair it in yourself. You have to lose your ego around it, you feel a bit silly at first but once that’s done, you talk about stuff you may have never talked about with anyone before. So the parenting that I didn’t get, in some ways I can’t blame them for ever. But in situations when I’m triggered now I don’t give myself such a hard time.”

Defence mechanisms

Overcoming addiction involves more than just giving up a chemical. Stu identifies co-dependency as the problem that usually underlines addiction, and it’s not until a person becomes aware of their co-dependent behaviour that it becomes easier to deal with. “You go, ‘These are my defence mechanisms, this is my dysfunctional way of coping’. A lot of what people are doing here is letting go of those old coping mechanisms. I always feel as if it’s grabbing on to one thing, letting go of the old thing and getting more functional.”

The daily programme at R12 is made up of group sessions, one-onone counselling, meditation, yoga and personal training in the gym.

Treatment at R12 is not cheap, costing about £10,600 for 28 days. Most clients have their fees covered by private health insurance providers or are lucky enough to be able to afford it. But the people behind R12 also offer some sponsored places to people without the financial means to pay for treatment.

One of the most challenging sessions Stu tells me about is the Process group. These bring problems and grievances to the surface.

Referred to as “sharing your reality”, Mike explains: “People can’t answer back or defend themselves [against criticism] but they can acknowledge [what’s been said], replying: ‘I hear you’. They can then bring it up the next day but in that moment the power is in the person speaking. It’s a good way of setting boundaries by saying, ‘What you said hasn’t made me feel good, so I’m letting you know so you don’t do it again’.

“The reason people can’t answer back is so they have to take the comment away and sit with it. You learn not to act impulsively.”

Where once a negative emotion or experience might have triggered a person to numb themselves with alcohol or drugs, Process groups show those taking part how to handle negativity without turning to substance abuse.

Opening ourselves up to criticism and learning to process anger is not easy but is arguably something we could all benefit from.

Empowering

The Resort 12 programme is intense and soul-bearing, and in my short time there I found the experience incredibly uplifting as well as empowering.

For Sean, his most empowering moment at R12 was being told that he was wrong. He had “protected himself” in life, believing he always knew best, that he was always right. “It’s helped a lot to be told that I’m wrong and I need to change. It’s helped me to breathe and take a minute and think about what I’m doing,” he reveals.

Meanwhile, Duncan is a little more confused about his hopes and fears for the future. “What scares me is giving up something that’s so integrated in my life,” he explains.

“If I stop going out to clubs, will I lose a whole bunch of my friends? It scares me that I might never drink again. Drinking for me hasn’t been all negative, it’s just that the negatives outweigh the positives.”

What he is quick to acknowledge, however, is a realisation that he actually likes living a quiet and healthy lifestyle, going to the gym and doing sport. He’s also started reading more and is currently enjoying waking up without a hangover but with a new sense of what he can achieve each day.

For Daniel, acknowledging his codependence has been the scariest thing. But sharing this realisation in R12 has shown him how common his situation is.

“I’m reminded that I’m much more similar [to other people] than dissimilar, so I don’t feel alone with it. That’s how recovery works, by relating to other people. But it doesn’t get better unless you address it.”

During his time at R12, Daniel discovered that he would close off parts of his life because he didn’t want to feel uncomfortable facing fears around sex, relationships and family. “Recovery encourages me to see that if I open the doors, I’ll grow.”

He adds how being clean brings clarity to his life. “The mood swings go, and your life has a gentle rhythm. You’re not always ‘happy, happy, happy’ but it’s a gentle rhythm and not a forced one. I’ve learnt to keep a light heart, to not be so serious.”

Mike says of his time in rehab: “What this has done is given me a safe platform to be kind to other gay men. Take away the sexual element and the flirting and there is an amazing kindness that gay men can share.

“The last rehab was so abhorrent and dark, but R12 has made me look at that relapse as a gift, to see that I don’t want to go back to that place. I take a lot of strength because I know that my past life is not sustainable for me.

“Going into Resort 12, I realised I was quite aggressive with my tone but I learned to acknowledge in me a kind of calmness, kindness, and just by being honest I came to realise how much I have helped other people too, just by us identifying with each other.”

While laws may change, LGBT+ people will always be a minority, and as such we will often find ourselves on the outside, frequently othered by society.

I have seen close friends enter rehab repeatedly. I have buried mates who allowed drugs to ravage their bodies. I joined the group at Resort 12 for just three days. My preconceptions of what I would find there couldn’t have been more wrong.

I expected to walk into a room of broken and damaged individuals. Yes, I met people who have seen the darkest of days. But far from being weak, they were among the bravest people I have ever encountered. In their despair they have found the strength to open up and bare themselves to strangers. I found inspiration in their courage to choose kindness over anger. In a world in which it’s so much easier to shout and hate, they have learned to listen with love.

While Resort 12 remains a private rehab facility for the lucky few who can afford it, its lessons are free for us all to learn. What became clear during my time at R12 is the healing power that sharing and talking with other LGBT+ people can bring.

And that’s something we can all start practising at home.

If you or a friend would like more information about the support and services available at Resort 12, contact the team at resort12.com