Comment | The Continuing Stigma of Hepatitis C

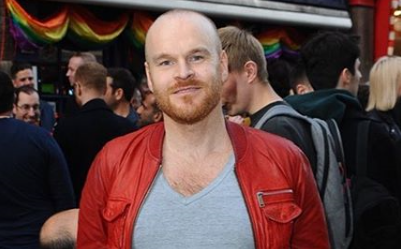

Philip Baldwin, LGBTQ rights activists and Hep C campaigner, on eliminating the virus

By Steve Brown

Words by LGBT rights activist and Hep C campaigner, Philip Baldwin

In Autumn 2017 I was asked a question by Attitude – did I think there was more fear and stigma around hepatitis C than HIV within the LGBTQ community? Since World Hepatitis Day falls on 28 July, I have naturally been thinking about this question very hard.

I was co-infected with HIV and hepatitis C in 2010, clearing my hepatitis C in March 2017. I always thought the stigma of hepatitis C worse, and still do two and half years on. But have attitudes within the LGTBQ community changed?

When I was diagnosed in 2010, I knew a little about HIV and nothing about hepatitis C. Over the coming years I found, time and time again, that gay and bi men were badly informed around hepatitis C.

Telling gay and bi men that I was HIV positive was comparatively straightforward.

Discussing my hepatitis C left me feeling especially vulnerable. I was afraid of rejection, not being able to have long term relationships and no longer being perceived as sexually desirable.

I was ashamed and insecure. And it was primarily my hepatitis C which was the cause of this, rather than my HIV.

I found it very hard, at first, to disclose my hepatitis C status. Whilst waiting to be treated for hepatitis C – and still healthy – I was also dealing with huge uncertainty in my life.

Before I felt comfortable talking about being co-infected, I had to gain self acceptance around both my HIV and hepatitis C.

I had heard HIV positive gay men referring to gay men with hepatitis C as “dirty” and “sluts.” I felt like in some ways I was being forced back into the closet.

Once I had the courage to talk openly about my hepatitis C, I had mixed responses from gay and bi men.

On one occasion, when I told a guy that I was both HIV and hepatitis C positive, he rejected me and then, the following day, he sent a text apologising and asking me out on a date.

Other gay and bi men congratulated me on being so open about my hepatitis C. Since 2017 the situation around hepatitis C in the UK has changed significantly.

Public Health England estimated that there were 160,000 people living with hepatitis C in the UK in 2017, with 40-50 per cent undiagnosed.

In April 2019, Public Health England released a report estimating that there are 113,000 people living with hepatitis C in England, with 69 per cent undiagnosed.

From 2014 – 2015 the NHS began to trial and then offer new direct-acting antiviral treatments, which have cure rates upwards of 95 per cent, last 8-12 weeks and are taken orally, with most patients experiencing no side effects.

The previous interferon-based treatments, were only 40 – 50 per cent effective, could last 12-18 months and were awkward to administer, as well as having debilitating side effects.

The NHS at first rationed the new treatments, on cost grounds, but have now cleared the waiting lists nationwide.

All my hepatitis C positive friends were treated successfully with the new direct-acting antiviral treatments in 2017 and 2018. As a consequence there are fewer gay, bi and trans people living with hepatitis C in the UK.

LGBTQ people are more likely to access STI testing and can now get treated for hepatitis C comparatively soon after being diagnosed.

Now the treatment for hepatitis C has changed, has there also been change in the stigma associated with the virus?

Most people, both within the LGBTQ community and beyond, are still unaware that there is a cure for hepatitis C.

From the gay men I chat to at events to MPs in Parliament, a significant proportion are surprised when I tell them about the new direct-acting antiviral treatments for hepatitis C.

It is the first blood-borne virus we have been able to cure and, as such, is something we should celebrate vocally.

I get gay and bi men, who have been diagnosed with hepatitis C, reaching out to me on social media or emailing my website because they are unaware of treatment options.

I have also heard from doctors, charities and patient support groups that some people are so afraid of side effects following failed interferon-based treatments, that they are reluctant to access the new direct-acting antiviral treatments.

There continues to be a massive amount of misinformation surrounding hepatitis C.

We need to ensure that more is done to inform the LGBTQ community about hepatitis C, and especially the great news that the virus can be treated effectively. This is the key to finally defeating the stigma of hepatitis C and ultimately eliminating the virus itself.

The Hepatitis C Trust helpline, staffed by people who have experience of the illness themselves, is 020 7089 6221.