Bad Habit’s Alana S. Portero on Love, Language and Trans Survival (EXCLUSIVE)

Spanish trans woman Alana S. Portero has captivated the world with her stunning debut novel Bad Habit, one of the most talked-about books of the year.

Alana S. Portero is a highly acclaimed Spanish writer, poet, playwright and theatre director. She co-founded the theatre company STRIGA, and is a passionate advocate for LGBTQ+ rights, giving a platform to the experiences of trans women.

Bad Habit, Portero’s debut novel, is a powerfully moving coming-of-age novel following the narrator, a young trans woman, in 1980’s Madrid. It has enjoyed phenomenal success, translated into multiple languages across the world. It has been tenderly translated into English by Mara Faye Lethem.

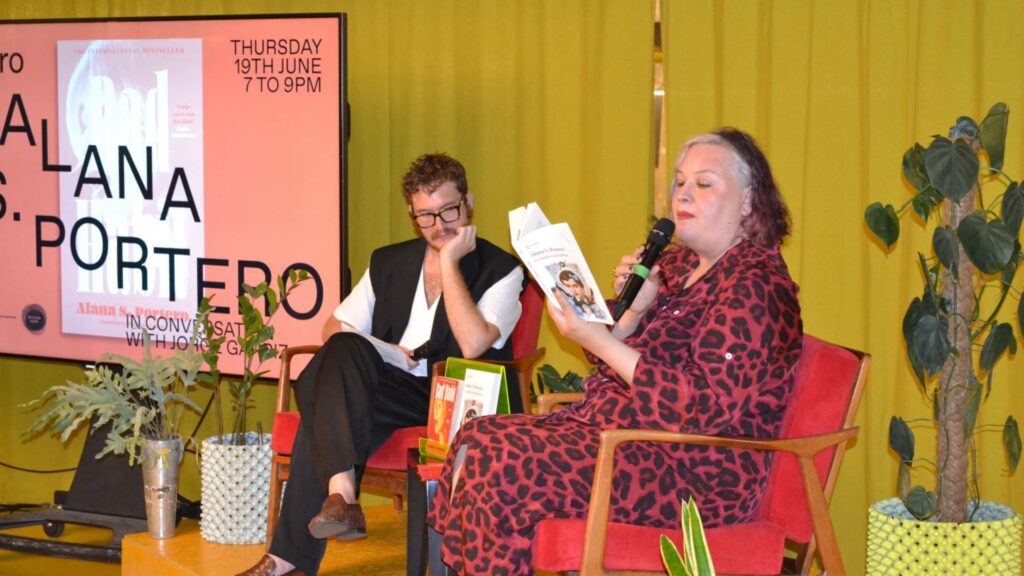

To celebrate the fifth Anniversary of Romancero Books, a cultural platform promoting Spanish literature in the UK and its translation to English, Attitude was invited to the paperback edition launch of Bad Habit at Second Home, an event that was organised in collaboration with the Spanish Embassy in the UK and their Office for Cultural & Scientific Affairs and Instituto Cervantes Londres. We sat down with Portero to discuss this incredible book that has captured our, and the world’s attention.

Bad Habit offers moments of tenderness, humour and beauty, amidst so much rawness and pain. Do you think this is typical of a ‘trans’ or ‘queer’ view of the world- that we can find light in the middle of disaster?

Absolutely, yes. Of course, tenderness and hope can be found anywhere, but I think that as queer people, we are adept at finding glimmers of light, because for us it is absolute survival… We’ve had to look for cracks of light, and if we haven’t found them, we’ve had to invent them. We’ve had to be very gentle towards ourselves because of the harsh world we inherited- a world of harsh words, attitudes, and very little tenderness. We had to be self-soothing, we had to take care of ourselves. So I think there is a queer tenderness that is very specific, but it is also very wise. I think it’s part of our legacy to the world.

Your book has been an incredible success, translated all over the world. You told Dua Lipa in an interview that three of your main characters ‘The Moirai’ were based on ten or twelve women that you knew in real life. Who were they, and how did you condense all those memories and references into three such formidable and iconic women?

They were all women I met on the street when I was 13 or 14 years old, when I was looking for my ‘other mothers’… I was looking for someone to take me by the hand, to take me under their wing… And these were the women I found, working on one of those deceptive streets in Madrid, or on Calle Ballestra, in Malasaña. They were exactly what I was looking for. They took care of me, welcomed me and protected me a lot. I didn’t have to explain anything to them, because they knew straight away what it was that I needed and who I was.

I consider them my ‘other mothers’, the most important women in my life. I wanted to write a novel to make that abundantly clear. And because it was my first novel, I didn’t want to complicate it too much. I distilled them into 3 characters to make things easier, because a chorus of 10 to 12 of them would have been a lot to deal with, especially these type of women.

So, to distil them into just three characters I went through a tender memorial process. I closed my eyes and thought about the first impressions I had of them, the phrases of theirs that I still remember, because none of them are alive anymore. The phrases, anecdotes, and the moments that really impacted me, and I took notes of those impressions, intuitions, and those free memories that have etched themselves in my memory. And like strokes of paint, I began to paint them.

One of them, Eugenia, is very much based on one particular woman… more than half of that character, because she was the most important to me. She took care of me a lot. She was a key person in my life, and with her I went through a more precise exercise of remembering, and I crafted and embellished her fictional form to pay homage to her, to give her a crown.

And that’s how I created them.

There is a slight language barrier between the narrator and one of the characters in the book, a deep love interest. Sometimes we don’t have the words, even in our own language, to express what we feel. And yet, a connection happens all the same. What role do you think language, or its absence plays in how we care for, accompany and love our trans siblings?

I think language has its limits. And you push and force those limits to try to be as precise as you can when loving deeply. But I think that as human beings, as queer human beings, we have developed a universal language of gestures. A way of looking at ourselves, where you can walk into a room, recognise the ‘queer gaze’ and immediately know that you are safe and sound. It’s a very difficult thing to narrate, but I wanted to try to get that across.

It is something that unites us, a queer mother tongue which is about gestures and glances, because historically we’ve had to carefully look for our sexual experiences without saying a word for our own safety. Looking to see if the person in front of us could respond to that same desire. We had to learn how to detect when someone was like us, and to protect them if they were suffering, away from public view.

We developed a universal language of queerness, which I think is one of the greatest languages, one of the greatest gifts we have given to humanity as queer people. People don’t know how to translate it, we have to try and force words to do the job. Use words as best we can to make it understood and to communicate our stories.

I am a great believer in that language of gestures and glances, I think that intangible language has saved the lives of many of us, or has made our lives much more bearable. It’s very difficult to teach, because I think like all languages, you yourself must learn them, no one can teach you, only they can teach themselves.

In Bad Habit, the narrator doesn’t come out to her family, which comes across as a conscious creative omission. As readers, are we supposed to be left with that doubt that despite it being a deeply loving family, it would still result in something deeply painful and difficult for her?

Difficult, at least, yes, because of the historical and social context of that family. I believe that first the narrator had to come out for herself, that final act of liberation, giving yourself permission to be who you are. And that was the most difficult thing. She doesn’t talk to her parents, because her parents don’t have the tools to understand her, and nor does she. Because of fear, above all, she is a woman dominated by fear, for 30 years of her life.

I want to believe that once that fear is overcome, and that woman understands herself, everything else gets easier, but I prefer to leave it to the imagination of the readers because each coming out story is unique and has very specific context. And I wanted readers to imagine what would happen.

I imagine a difficult, but beautiful coming out for this narrator with her parents. For them, she is not a stranger. They just don’t know how to put a name to what is going on, because neither has she been able to. I like to think it would relieve her parents, they have seen their daughter suffer all her life, without really understanding why, so I imagine her coming out to be a relief for the whole family.

What would you like to say to our trans readers who in such hard and uncertain times, feel vulnerable, scared or lonely?

First of all, that they have every right to feel that way. We have to be accompanied by those who love us, in that fear, because it is inevitable, and fear can also protect us.

Throughout the history of humanity, trans people have lived in societies. We’ve been persecuted, made into gods or goddesses, been tortured, cast aside, fetishized, and we have always resisted. We have always been here. And there has never, ever been a human movement, no matter how aggressive, that has ended our presence in the world.

So, we are going to keep going, we are going to continue. And we’ve never had it easy. And it’s precisely for that reason that the battlefield is ours, not theirs. We are on our turf. It’s hard to see it that way, but this is our terrain. There is nothing that we know better. So therefore, we’re going to win.