The Compton Cafeteria riots and the birth of the militant queer movement

By Josh Lee

This feature was first published in Attitude issue 273, August 2016.

Everyone has heard of the Stonewall Riots – but the militant LGBT movement was born three years earlier – and half a century ago now – at an all-night cafe in a seedy part of San Francisco

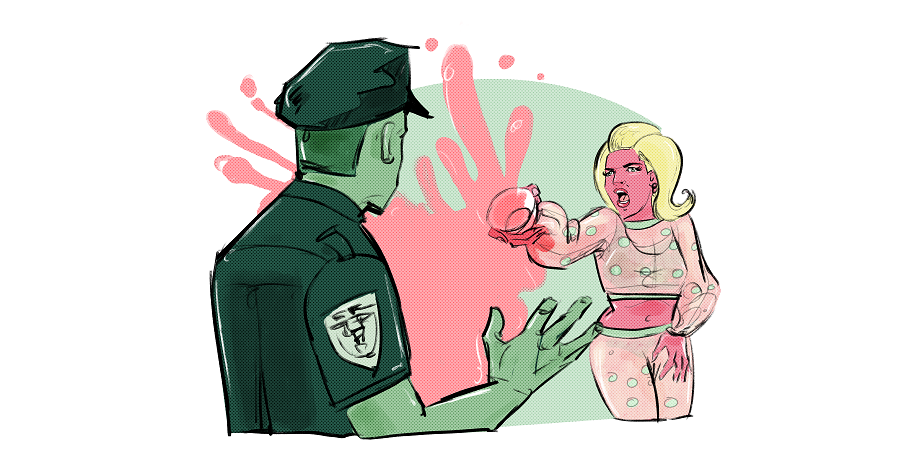

A drag queen threw a cup of coffee into a cop’s face as he tried to arrest her. In a flick of the wrist, the place erupted. After suffering years of insult and ostracism, the anger burst forth into a flood. Drag queens, hustlers and transgender youths threw sugar bowls, knives, forks; anything they could get their hands on. Some used their heavy handbags to batter the policemen. But this wasn’t at New York’s famous Stonewall Inn. It was at an all-night coffee shop on the other side of the country — in 1966, three years before the more-widely known protest.

As the cafeteria’s windows were smashed, the police retreated. The violence spilled into the streets. It was noisy, public — and unprecedented.

The fighting was eventually quelled by the arrival of large numbers of police vans but the point had been made. No longer would the drag queens and the hustlers and the “hair fairies” put up with being harassed. They were the way they were, and they weren’t going to change. And if they weren’t going to change, then the institutions, from the cops to the courts, would have to. The downtrodden had had enough.

The riot at Compton’s cafeteria, in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, was arguably the first visible sign of the fight back, the first collective act of what the author and professor Susan Stryker calls “collective militant queer” resistance. The outcasts of the Tenderloin were beyond marginal: they were encouraged to think of themselves as the lowest of the low and were treated as such by the authorities. The habitués of Gene Compton’s, on the corner of Taylor and Turk streets, had very little to lose: at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in almost every state, the effeminate and trans youths who flocked to the all-night café had long been disowned by their parents. Forced to live outside the system and constantly arrested by the police’s notorious TAC squad as female impersonators, many turned to prostitution simply to survive.

By 1966 the Tenderloin had been the city’s vice district for many decades. But it was feeling new pressures. As Professor Stryker explains in her 2005 documentary film of the event and the times, Screaming Queens, many of those who gathered at Compton’s had been forced into the district by deliberate social engineering: the poor and the outcast and the gender deviant were all shoved into the same zone of dirty streets and rough hotels. During 1966, even that haven was under threat from redevelopment and urban renewal in the surrounding districts. To accommodate people who had been moved on from there, hotels such as the Hyland threw out its regular gay and trans residents.

At the same time, the escalation of the Vietnam War brought concerns about prostitution and its effect. Thousands of young conscripts were in San Francisco, waiting to be shipped out, and were willing to pay for sex. The Tenderloin was subject to several vice sweeps, with drag bars bearing the brunt. At the same time, divergent masculinity was suspect: long hair, if not feminine clothes, denoted someone who was not “normal” and certainly didn’t want to fight in an undeclared war more than 7,000 miles away. Looking different was seen as un-American, if not traitorous.

Among the Tenderloin types were “hair fairies,” who wore men’s clothes but teased their hair as women did and wore make-up. The activist Adrian Ravarour remembers his friend Billy Garrison. “He described himself as a hair fairy, which meant that the clothing he wore was heterosexual — jeans and a shirt — but he had his hair up and sprayed so it was like a beehive. He wore make-up, eyebrow pencil, rouge, lipstick and foundation, and he did his nails.” Along with the transitioning young men and the drag queens, to many people this was a visibly disturbing mutation of masculinity.

The final factor in the Compton’s riot was the slowly increasing militancy of gay politics. Events gathered pace during the first half of 1966. In February, the National Planning Conference of Homophile Organisations was held in Kansas City: an ambitious attempt to create a nationwide gay movement.

In April, a “sip-in” was held in New York, protesting against the many city bars that refused to serve homosexuals. In May, there was a motorcade in Los Angeles to protest against the exclusion of homosexuals from the armed forces.

The same few hundred or so activists continued ploughing the furrow that they had since the 1950s, but another generation was also starting to appear.

In July, a new kind of group was set up in San Francisco by members of the radical Glide Memorial Church, situated at Taylor and Ellis, just two blocks from Compton’s. Realising the depth of the social problem right in front of their noses, they talked to the youths of the Tenderloin about their troubles and their needs.

Encouraged and sheltered by Glide ministers, young runaways and hustlers formed a group called Vanguard. It held weekly dances in the church’s basement, distributed free food and clothing, and produced a magazine.

Hustlers such as Keith Oliver and Adrian Ravarour had already begun to organise their peers. “People were being done down by their environment, by being called names, being told they were worthless, by families who threw them out,” remembers Ravarour. “I saw Vanguard as an opportunity for people to stand their ground.”

Inspired by the Civil Rights movement, they stated their complaints in a July 1966 leaflet called We Protest. They complained of police harassment of youth, being called queers and pillheads, and of being placed in the position of being outlaws and parasites.

At the bottom of the publication was the promise: “Vanguard pledges that its youth will be able to provide the help and concern adults seem unable to muster.”

It was estimated that there were about 1,000 young men and women, aged between 12 and 25, working in the Tenderloin as prostitutes, pimps, thieves and pill pushers.

Some of these were runaways, others already hardened by a life of loneliness, danger and constant police harassment. As one of them, calling himself Jean-Paul Marat — after a leader of the French Revolution in the 18th century — told the weekly underground newspaper, The Berkeley Barb, “When I first got to town I was stopped by the police 17 times in three days. On the last of these, I ended up with a dislocated jaw. That sort of thing happens all the time.”

In July 1966, the San Francisco-based gay newsletter Cruise News and World Report stated that, “Vanguard is an organisation whose membership is drawn right off the streets of the city, with aims of self-improvement of the lot of hair fairies, lost kids, hustlers, young adults without family ties, and all the other varied types that frequent Market Street, seeking entertainment, money, a meal, a change of clothing, or just kicks.”

The first issue of Vanguard, published in August, featured poetry with titles such as The Hustler and The Fairytale Ballad of Katy the Queen, instructions on what to do if arrested, and an editorial by Marat, by then the group’s elected president, who looked like one of the Rolling Stones with his Mod jacket, epaulettes, and Brian Jones bob.

It also included a powerful piece entitled Central City: Profile of Despair, written by Mark Forrester.

It delivered an all-out critique of American hypocrisy. Forrester wrote: “In the least, all the wino destroys is himself, while the businessman, through the philosophy and methods he employs, taints an entire generation of young people with a slavish mendacity to the lowest denominator of public opinion. Does the hustler damage anyone but himself?”

This was a new kind of attitude that turned things upside down. It wasn’t the hustlers and the drag queens who were wrong, it was American society.

As Forrester concluded, the youths of the Tenderloin did no harm. By contrast, the businessmen and what the writer called the Middies, the Silent Majority, managed to hurt almost everyone else they touched; black men and women, the poor, the queers, the outcasts, “and all that their sanctimonious religion tramples on, all that their (money) greases up for a quick sale. Let’s start asking the right questions of the right people by examining their beliefs and actions.”

In the same month that the first issue of Vanguard was published, those questions were asked in a very direct and public manner at Compton’s.

As Professor Stryker discovered, the café’s popularity among young gay men, hustlers and drag queens came from its status as an all-night venue and the fact that, for a long while, the evening manager was “an older effeminate homosexual,” who created a sympathetic atmosphere. When he died, the management introduced a 25c cover charge to sit in the restaurant, and hired security guards to harass the clientele.

On 18 July, members of Vanguard had picketed the venue in protest at the way that the younger residents of that area were treated. They were filmed and televised. The bad feeling built up and, on that night in August, it exploded.

As Guy Strait related in the Cruise News and World Report, events were triggered by a young customer who threw a cup of coffee over a policeman. “With that, cups, saucers and trays began flying around the place and all directed at the police. They retreated outside until reinforcements arrived, and the Compton’s management ordered the doors closed.

“The gays began breaking every window in the place, and as they ran outside to escape the breaking glass, the police tried to grab them and throw them in the [police vans]. They found this no easy task, for gays began hitting them ‘below the belt’ and drag queens [smacking] them in the face with extremely heavy handbags.

“A police car had every window broken, a newspaper shack outside the restaurant was burned to the ground and general havoc ensued that night in the Tenderloin. The next day, drag queens, hair fairies, conservative gays and hustlers joined in a picket of the cafeteria, which would not allow the drags back in.”

Shortly afterwards, Vanguard issued a press release that reinforced the way in which they saw their struggle as part of a wider battle. It said, “The Vanguard demonstration indicates the willingness of society’s outcasts to work openly for an improvement in their own social-economic power. We have heard too much about White Power and Black Power, so get ready to hear about Street Power.”

Photographs of the time show the hair fairies looking magnificent with their teased hair, and wearing mohair cardigans and super tight, calf-length trousers — seen as an affront to every idea of masculinity.

In 1966, freedom was in the air, in songs on the radio, in the clothes and the long hair sported by America’s young, as well as by the protests against the Vietnam War and America’s endemic racism.

The Compton’s riot showed that violence was necessary to make the point to those who would not listen, to make a show of strength and self-worth in the face of almost universal rejection.

It was the first spark in the revolution that Stonewall would broadcast around the Western world, and, as with that event, the resistance was sparked by youths whom society had condemned to the scrapheap.

Words by – Jon Savage

Illustrations – Ego Rodriguez