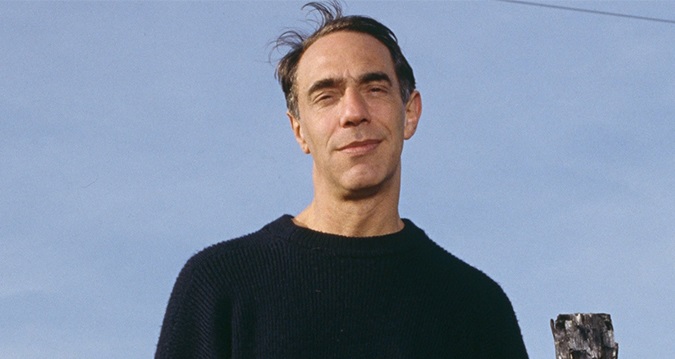

Remembering iconic filmmaker and LGBTQ activist Derek Jarman 25 years after his death

February 19, 2019, marks 25 years since the filmmaker died from an Aids-related illness.

By Steve Brown

February 19, 2019, marks the 25th anniversary of the death of the openly gay, iconic filmmaker Derek Jarman.

In 1986, he was diagnosed as HIV-positive and discussed his condition in public. In 1994, he died of an Aids-related illness in London, aged 52, 25 years ago to the day.

Now, to commemorate his work, English Heritage unveiled a Blue Plaque in London dedicated to the LGBTQ activist and the BFI will be releasing a new collection of his greatest works.

In Attitude’s March Style issue – which is available to download and buy in store now – Brian Robinson looks back at the gay filmmaker’s life and career.

Alchemist, magician, lover, friend, activist, poet, painter, genius — there were many sides to Derek Jarman.

For a generation he was a hugely influential, high-profile figure at a time when there were very few famous out gay men. His career as an iconoclastic filmmaker gave him a platform which he was happy to use as a campaigner.

Jarman created a unique body of inspiring work, almost every frame as rich as a painting, from his sexy vision of Roman soldiers with a young saint frolicking by the sea in 1976’s Sebastiane (with all the dialogue in Latin) to his final work, the experimental Blue (1993) and his posthumously released Super 8 collection Glitterbug (1994).

To understand Jarman you have to see and appreciate his films. It’s also important to understand that he was an artist whose life was a major part of his artistic creation.

And his art was an extension of his social and personal life, bringing a talented group of friends, lovers and collaborators together with the air of an anarchic, circus ringmaster.

Jarman died 25 years ago, in February 1994, at the age of 52, the day before a key vote on the age of consent in the House of Commons.

He and many others had campaigned for an equal age for both gay and straight sex but the Commons would, on that occasion, reduce it to 18, rather than 16.

In the years since his death, Jarman has continued to be celebrated for his magical and daring creations: the garden at his Kent cottage in Dungeness, his writings, his paintings and his cinematic celebrations of queer history and culture.

In person, Jarman was an imposing and attractive but approachable figure whether you met him at a bar, in the street, on Hampstead Heath or at a film festival.

He had a mischievous sense of humour and an irrepressible love of sex. He was a regular on the London gay scene and had been since he came out while at university in London (he was at King’s College before going to the famous Slade Art School) in the 1960s.

Although born in London, he spent his early life surrounded by the classical beauty of Roman architecture and sculpture, which had an enduring influence on him.

At university he studied art history, fine art, history and literature. His life-long passion for history, art, the occult and homosexuality were to provide a rich seam of inspiration. His time as a fine artist offered promise but he was diverted to the world of theatre and film design.

He worked on a ballet for William Walton at the Royal Opera House, then, through a chance meeting on a train, he was introduced to the film director Ken Russell, for whom he created a daring set design for The Devils (an adaptation of Aldous Huxley’s tale The Devils of Loudun).

Jarman’s life was full with the people he met or worked with. Tilda Swinton first appeared on film as a prostitute in his biopic of the gay Renaissance painter Caravaggio and she became his muse and a devoted friend.

He was part of a wave of artists living in lofts near London’s South Bank, taking over derelict warehouse buildings for an experiment in communal living space which functioned as a gallery and a studio as well as a home.

While there, he came face to face one morning with notorious film director Pier Paolo Pasolini who was scouting locations for a movie. Away from the big screen, Jarman filmed Marianne Faithfull for the release of her album, ‘Broken English’, he worked with Bruce Weber and the Pet Shop Boys on several pop videos and also made ‘The Queen is Dead’ for The Smiths.

The BFI’s new Blu-ray, Jarman Volume Two 1987-1994, has a range of extras which reveal just how creative he was, appearing in other people’s films, including many rare and little-known pieces such as the angry, anti-Clause 28 piece Clause and Effect, his performance as Pasolini in Julian Cole’s Ostia plus interviews with producer James Mackay, fellow filmmaker John Maybury and designer Sandy Powell.

Jarman often struggled to get financial backing for his film projects but he made brilliant use of what he could cobble together and worked selflessly with minimal resources.

The Last of England (1987) is a prophetic vision of a dystopian Britain where the brutality and lack of humanity evident in the social policies of Margaret Thatcher’s government are seen to have run their logical course and society is divided into the wealthy and the dispossessed.

Jordan, the famous punk icon of his 1978 film Jubilee, reappears in a ballet around a bonfire in a highly notable Super 8 sequence. Jarman was one of the first public figures in Britain to come out as HIV-positive after being diagnosed in 1986.

What is extraordinary is the burst of creativity which followed in the next seven years. War Requiem (1989) was Laurence Olivier’s final film role and he stars as a military veteran against the soundtrack of Benjamin Britten’s music, speaking Wilfred Owen’s poetry alongside images of great brutality and a visceral attack on the morality of war.

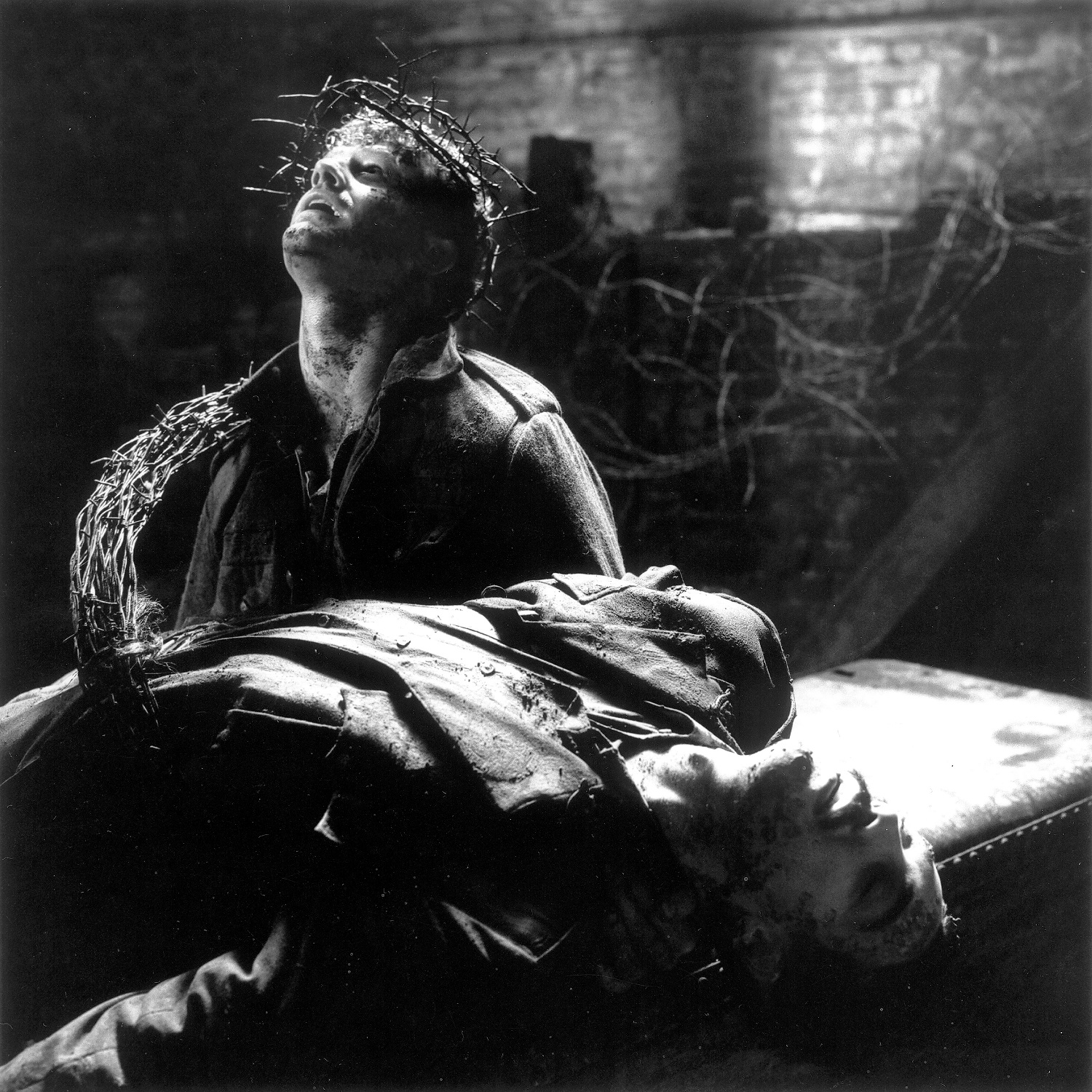

Its downbeat darkness may be a reflection of Jarman’s coming to terms with his own mortality. The Garden (1990) is another attack, this time on the role of organised religion, using a poetic vision of his Prospect Cottage garden and its surroundings as a sort of vision of the Holy Land.

It was shot on a mixture of Super 8 and 16mm and features Christ and Judas as gay lovers.

Edward II (1991) is another biopic and was part of Jarman’s project to rescue queers from historical erasure.

Swinton is magnificent as the scheming, glamorous Queen Isabella. Members of the Aids activist group Outrage! were featured protesting against homophobic attacks. Jarman’s partner Kevin Collins, aka Keith, plays the jailer who kills Edward.

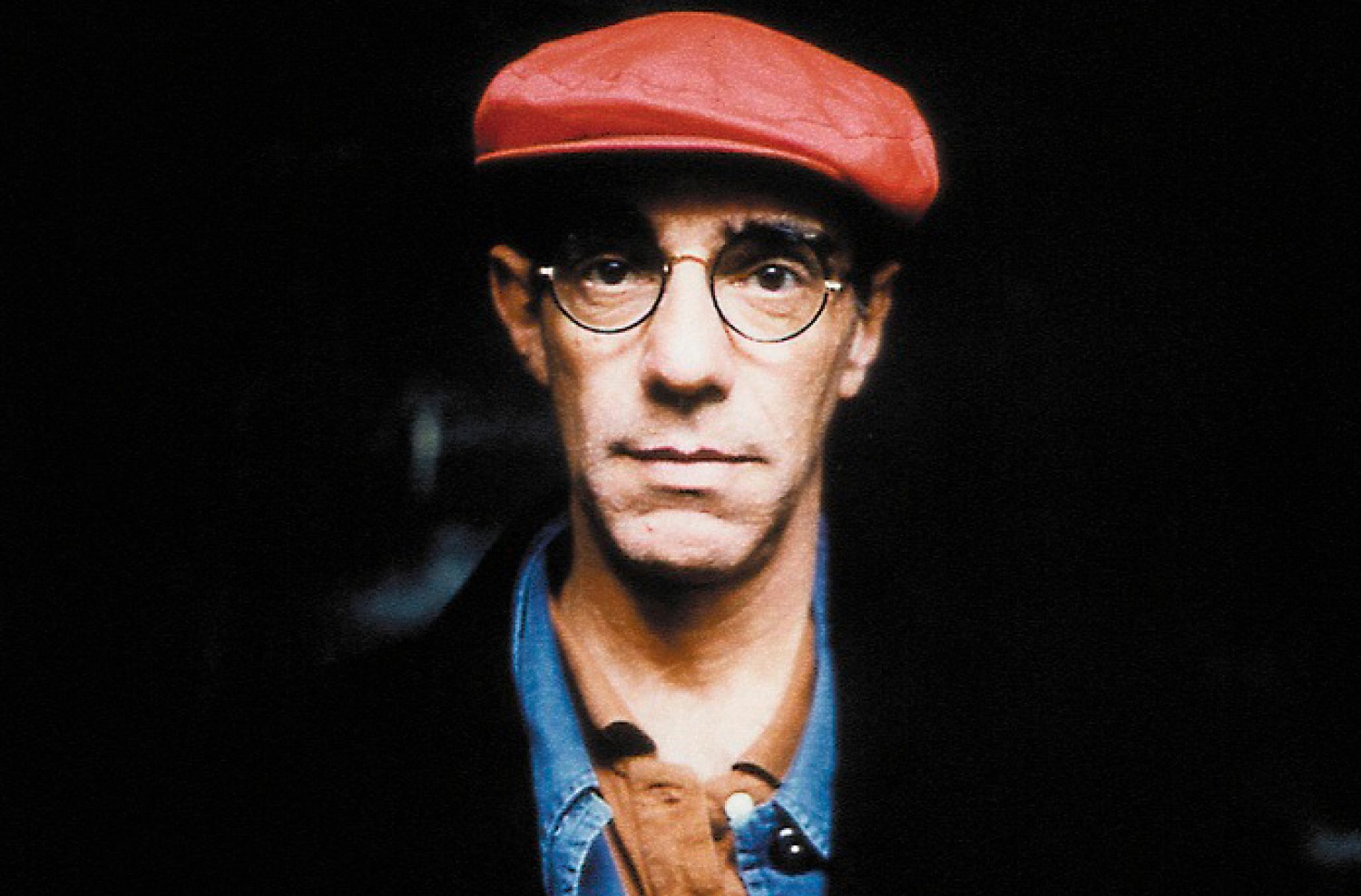

Wittgenstein (1993) is a triumph of costume and script, creating a portrait of the gay Viennese philosopher that is playful and intense, based on a script co-written with Terry Eagleton, who was appalled at Jarman’s treatment of it.

Blue (1993) is a mixture of poetry and music, performed by many of Jarman’s favourite collaborators including Swinton and composer Simon Fisher Turner. The image seen is a projected blue rectangle, inspired by the fact that Jarman was almost completely blind.

On the credits, Blue is dedicated to “HB and all true lovers.” HB stood for Hinney Beast, Jarman’s nickname for Keith. They met at the Tyneside Lesbian and Gay Film Festival in 1986 and there was an instant attraction which led to Keith moving in, as a kind of platonic lover.

Keith played many roles in Jarman’s life. As well as acting in his films, he was also a beautiful muse, companion, artistic collaborator and helper. The last words in Jarman’s diary are “Birthday. Fireworks. HB true love.”

Keith died of a brain tumour last August but he had worked tirelessly to maintain Derek’s legacy.

One of the glories of the BFI collection is a chance to see Jarman’s earliest work from the happiest time of his life, his early experiments in 16mm and Super 8 with friends such as Andrew Logan and Duggie Fields.

The films are camp, beautiful and evocative of a liberating way of making art. The infectious enthusiasm of people having fun by dressing up, showing off or interacting with each other is a delight to watch.

There is a special pleasure in Jarman’s love of ritual, performance and sexual ambiguities.

What comes across in contemplating his work as a whole is that Jarman was passionate about art, life and politics. He was in love with a particular brand of Englishness, he had a lyrical and intelligent respect for history and was drawn to celebrate homosexual love.

The BFI’s Jarman Volume Two 1987-1994 is released on Blu-ray on 25 February and is dedicated to Keith Collins.

You can get your hands on a copy of Attitude’s March Style Issue now.

Buy now and take advantage of our best-ever subscription offers: three issues for £3 in print, 13 issues for £19.99 to download to any device.