Peter Tatchell relives first communist country LGBT+ rights protest 50 years on: ‘I was marked as a troublemaker’

"There was no place for LGBT+ people"

50 years ago, in 1973, the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students was set to be held in East Berlin, the capital of what was then communist East Germany, from 27 July to 5 August.

Its theme was ‘Anti-Imperialist Solidarity, Peace and Friendship’, and 30,000 delegates representing progressive youth and student organisations from 140 nations were expected to attend.

At that time, I was a 21-year-old left-wing student and an activist in the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in London.

The festival struck me as a great opportunity to promote LGBT+ freedom on an international scale — particularly to communist countries, where queer rights were non-existent.

“There was no place for LGBT+ people”

In 1973, homosexuality was still illegal in the communist states of Albania, Yugoslavia, Romania, and the Russian-dominated Soviet Union. While it had been decriminalised in communist Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and the eastern half of a divided Germany, LGBT+ people were under police surveillance.

Prejudice and discrimination were rife. Communist morality promoted the “socialist family.” There was no place for LGBT+ people. They were often persecuted as “enemies of the state.”

Keen to challenge this communist homophobia, I applied for membership of the British delegation to the festival. Surprisingly, I was accepted as a representative of the GLF — this was probably because the secretary of the delegation was secretly gay and sympathetic to our organisation.

In late July, I set off for East Berlin, sailing from Harwich to Hamburg on the overnight ferry, and then hitch-hiking across West Germany to Berlin. Hidden under my clothes and in a rucksack and suitcase, I carried 300 LGBT+ rights pamphlets, plus 2,000 leaflets in English and German for distribution at the festival.

Knowing that protesters in East Germany routinely received long jail terms, I was terrified. But I gambled that my western passport and the fear of bad media publicity would enable me to get away with being deported or spending a few days behind bars.

“I carried 300 LGBT+ rights pamphlets, plus 2,000 leaflets in English and German for distribution at the festival”

On the opening day of the festival, I marched with the British delegation through the centre of East Berlin, cheered by a million East Germans lining the route.

Later, I leafleted other delegations but their response was mostly hostile. French delegates said: “P**s off, you b*****ker. We like women!” The US delegation was also dominated by the anti-gay left. It had refused to accept members from LGBT+ organisations, so I leafleted their rooms. All hell broke loose.

The US delegates complained to the British delegation and the East German authorities. Some wanted me expelled from the festival. I was hauled before the steering committee of the British delegation and given a severe reprimand.

From then on, I was marked as a troublemaker. There was a concerted effort to prevent me from speaking on LGBT+ rights. Although I applied to address five of the scheduled conferences, my applications either went missing, or the line-up of speakers was declared to be full.

“I was marked as a troublemaker”

The same stonewalling happened when I applied to lay a pink triangle wreath at the site of the former concentration camp at Sachsenhausen, in memory of the thousands of homosexuals exterminated by the Nazis. The East German government banned me. I reluctantly agreed to forgo the wreath-laying in return for an invitation to speak about youth rights at the conference. Wanting to end the row, they agreed.

But when I spoke, advocating gay liberation, my microphone went dead. Four hefty officials, probably the secret police, the Stasi, tried to drag me off the stage. I clung onto the podium. They could not remove me.

Many delegates cheered me on and started a spontaneous slow handclap. Faced with open revolt, officials relented. I resumed my speech, but the simultaneous language translations omitted or distorted much of the LGBT+ content.

As I left the auditorium, dozens of delegates clamoured for my leaflets. I later learned that they were secretly circulated in communist countries for many years afterwards.

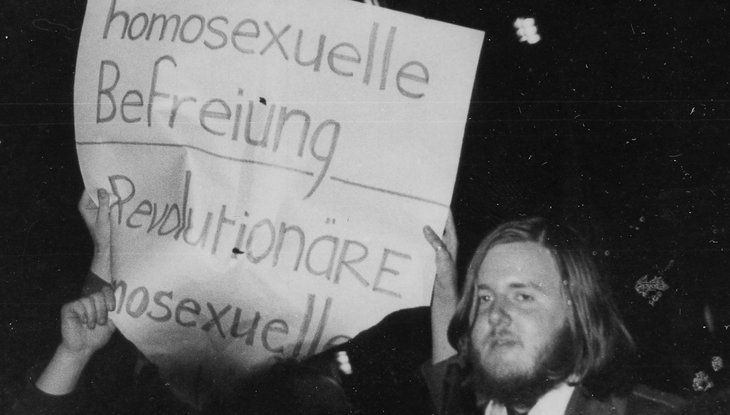

In the evening of the final day of the festival, all the national delegations were due to participate in a closing rally in Marx-Engels-Platz. Delegates were encouraged to make their own banners. I made a placard saying “Homosexual Liberation! Revolutionary Homosexuals Support Socialism!” in German.

On the reverse side, in English, it read “Gay Liberation Front — London”, and underneath that, in German “Civil Rights for Homosexuals”. I concealed the placard inside a large bag and made my way to a restaurant near Alexander Platz for a pre-rally evening meal.

As I finished eating, I was approached by three East German officials in trilby hats and trench coats — the trademark attire of the dreaded Stasi. They asked if I intended to carry a “homosexual rights banner” during the closing ceremony. After a moment pausing to wonder how they knew, I confirmed that I did.

“One assailant threatened to kill me. My placard was ripped in half”

Sensing trouble, I tried to leave. The officials blocked my way. They were backed up by a squad of East German police who appeared from behind a screen. It was a pre-planned operation to thwart me. They tried to drag me out of the public area of the restaurant into the kitchen. I resisted. A scuffle broke out. It attracted attention from passers-by who crowded outside, peering through the windows and taking photos.

Perhaps this made the Stasi fear unfavourable publicity, because I was let go with a warning that “under no circumstances” would I be allowed to carry an LGBT+ banner at the rally.

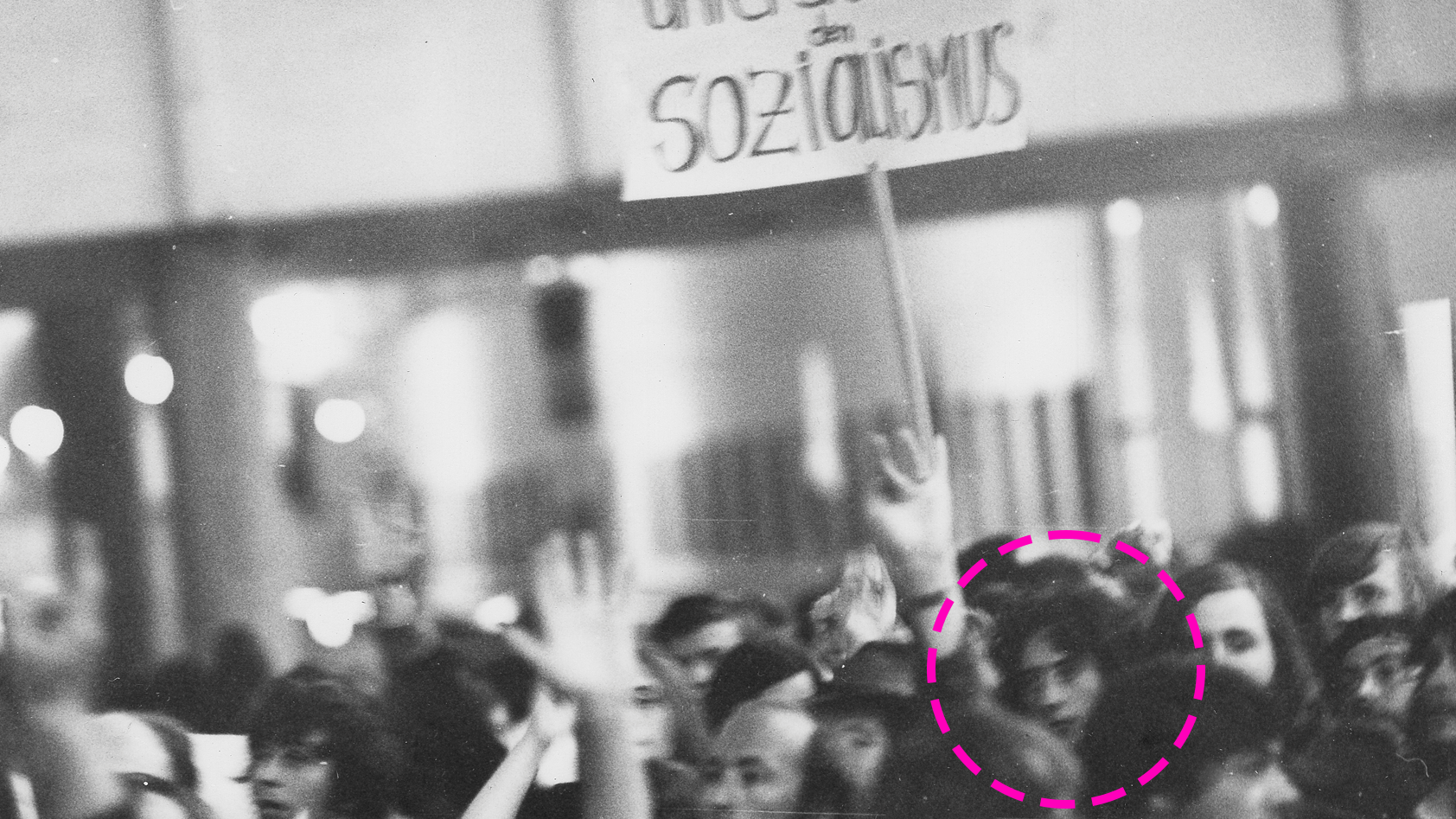

I then joined the British delegation, holding my placard aloft defiantly. Within minutes, an angry mob of homophobic communists appeared and started attacking me. I was punched, kicked, and spat on, and battered over the head with banner poles.

One assailant threatened to kill me. My placard was ripped in half. All that was left were the German words “homosexuelle befreiung” (homosexual liberation).

Some of the British delegation rallied to my aid, shepherding me away from the violence. Disregarding police threats, and to the astonishment of hundreds of onlookers, we chanted gay liberation slogans in German and distributed the remaining leaflets I had brought from Britain.

“I was filled with a mixture of fear and exhilaration”

Ignoring police demands that we disband, about 30 of us decided to march to Marx-Engels-Platz to join the final rally. We had gone barely 40 yards when we were again set upon by anti-gay members of our own British delegation. After fighting them off, we marched onwards with the remaining fragment of the placard held high.

Meanwhile, our attackers went to get reinforcements and returned with sticks and an angry posse of East German communist youth. We fled into the dense crowds. I ducked low, so I could not be easily seen and followed. After running non-stop, I eventually hid out on the roof of an apartment block.

I was filled with a mixture of fear and exhilaration: fear at the thought of imprisonment by the East Germans, and exhilaration that I had just staged the first LGBT+ demonstration in a communist country.

Against all expectations, I was not arrested, and a few hours later, I crossed the border back into West Berlin. A very lucky escape!

Peter Tatchell is director of the Peter Tatchell Foundation: petertatchellfoundation.org