LGBTQ Brazilians share their hopes and fears for the future under Bolsonaro

The rights of Brazil's LGBTQ community are under threat. We speak to six queer people living under Bolsonaro's far-right regime.

By Will Stroude

Words: Tim Heap

Photography: Francisco Gomez de Villaboa

Many Attitude readers will have dreamed of visiting Brazil for a holiday: sunbathing on the famous beaches of Rio, trekking through the rainforest and seeing the iconic Christ the Redeemer statue.

But there’s a much darker side to the South American hot spot, one that’s recently come out of the shadows.

Brazil’s new president, the former army officer Jair Bolsonaro, was inaugurated in early January. He’s the latest in the wave of far-right, authoritarian leaders who have come to power around the world in the past few years.

With almost three decades of political experience, 63-year-old Bolsonaro has carved out a reputation as a strident supporter of national conservatism and as a vocal opponent of social issues faced by minority groups.

He has called refugees “the scum of the earth”, told a female politician that he wouldn’t rape her because she didn’t “deserve it”, and has advocated torture, gun ownership and returning the country to a dictatorship.

“We will never resolve serious national problems with this irresponsible democracy,” he is reported as saying.

And when it comes to the LGBT+ community, he’s not been short of things to say either.

“I would be incapable of loving a homosexual son,” he said in 2011, adding: “I’d rather my son died in an accident than showed up with some bloke with a moustache.”

He had more to say in 2013, stating: “We Brazilians don’t like homosexuals,” and the following year asked, “Are [gays] demi-gods? Just because someone has sex with his excretory organ, it doesn’t make him better than anyone else.”

Since winning the election in October last year, with 55 per cent of the vote, he’s doubled down on many of his controversial remarks.

In his inauguration speech, he claimed his presidency would “unite the people, rescue the family, respect religions and our Judeo-Christian tradition, combat gender ideology, conserving our values.” Shortly afterwards, Donald Trump tweeted a message of congratulations.

With good reason, minority groups in Brazil are fearful of what his presidency will mean for their rights.

In January last year, research by LGBT+ watchdog group Grupo Gay de Bahia reported a 30 per cent rise in deaths as a result of homophobia in 2017, to an all-time high of 445 (including 58 suicides).

Now, emboldened by their president’s anti-gay rhetoric, Bolsonaro’s supporters are an omnipresent threat to queer Brazilians.

We spoke to six young creative people in the country’s largest city, São Paulo, to learn more about the reality of being LGBT+ in the age of Bolsonaro…

Dudx, 29, artist and activist

I’m lucky to have a wonderful family, who I’m out to. My mother is a social assistant and an activist who campaigns for the rights of people of colour, queer and poor people.

But Brazil as a whole is a conservative country, and the ox-bible-and-bullet lobby still reigns. That, plus a poorly articulated Left, and the conservative media, is why Bolsonaro won the presidential election.

The Brazilian media is summarised into two main channels: [the daily newspaper] Folha de São Paulo and Globo [a TV station], both of which are right wing. Globo is clearly interested only in profits and uses controversial speech to get what it wants.

São Paulo is one of the few cities in Brazil that has the space and opportunities for queer people to have an assumed life.

Originally, I’m from Campo Grande in the middle of Brazil, where I had to run to not be killed. Here in São Paulo, you can meet people from all over the world, which helps LGBT+ people feel less out of place.

I respond to Bolsonaro’s election through my work. I have an eccentric clown character which I use to criticise the macro-political scene, and recently I showered in spoiled food to talk about the misappropriation of school meals in public schools in São Paulo.

Since his win, it feels less safe to be openly queer. We need to be strategic about our lives and our community. We have a clear enemy who has no fear of us; every day we lose a trans person and the perspective is chilling.

Two days before Christmas, a hairdresser called Plínio was killed on Paulista Avenue, the principal street of São Paulo. He died with a knife in his heart, just for being gay, and the newspapers reported it as if Plínio had argued with his murderer and didn’t defend himself.

I have a privilege because I’m big and tattooed, and this provokes fear in some people, but spaces that I used to consider safe now feel less so.

But we need to remember that Bolsonaro is not the only enemy. We have a reactionary right-wing conservative government, and there’s a lot of work to be done.

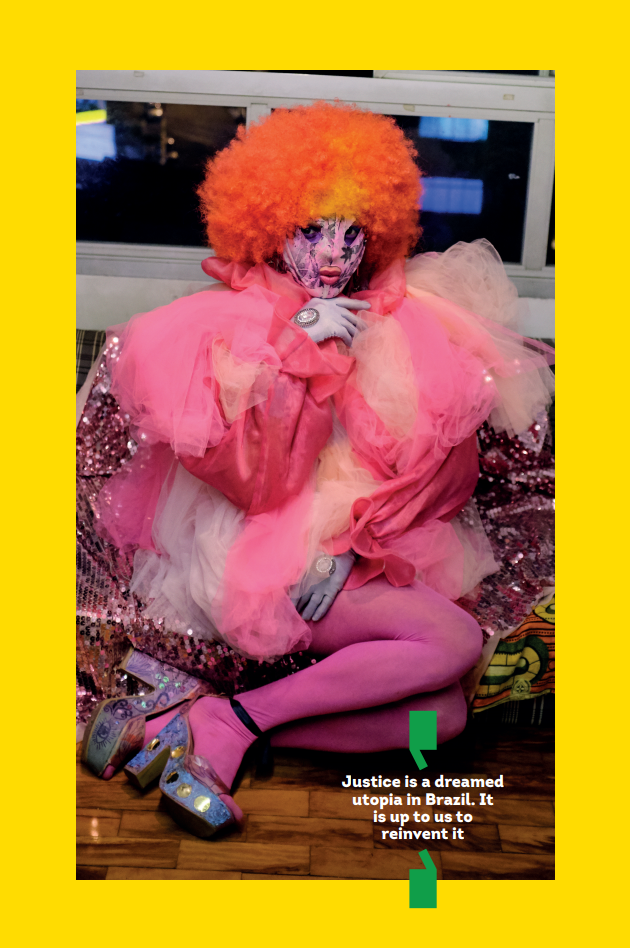

Ana Giselle, 22, multi-artist and ‘trans-alien’

I’m from Recife in the north east of Brazil, but live in São Paulo as an artist, writer, cultural producer and articulator of the rights of trans people and “travestis.”

The word “travesti” doesn’t translate but refers to a person assigned male at birth and who has a feminine gender identity. I describe myself as “transalien”, to give life to a post-human identity and to build a body that is free of standards, rules and cis normatives.

I’m also the founder of MARSHA!, a movement that pays tribute to trans people and encourages them to resist, and TRANSFREE, a project that helps trans people attend events free.

Bolsonaro’s win didn’t surprise me: the media and the majority of Brazilian people are fascist and intolerant, and he was just the spokesperson [for that]. The typical Brazilian lives in a profound state of social psychosis where the sense of having one’s own opinion has been lost.

As a travesti who endures violence every single day in every way, this election hasn’t changed my reality. Brazil has the most murdered trans people out of every country in the world. We already live in extreme social vulnerability and our lives are already all about resistance, politics and power.

My existence and resistance is my biggest response. My family is just my mum. She is the only person who didn’t deny me and she shares my political views. When the election result was announced, she called me to say that she loves me and that we will stay strong together. She said that as long as she lived, I did not need to be afraid of anything — this was the only reason I cried that night.

Of course, Bolsonaro’s win does put LGBT+ people’s rights and lives at risk but I believe he will not be able to [negate] all our achievements, all the little but important victories that have given our movement a sense of equality over time. There’s no turning back on the highway of liberty.

I do not believe in democratic politics. I do not believe in bureaucratic, administrative justice — there is a complete absence of justice in this country. Justice is a cultural invention, a dreamed utopia in Brazil and in the world.

Unfortunately, it is up to us — marginalised, black, trans, gender nonconforming people who never knew justice — to reinvent it, so that one day we can enjoy it.

Mauricio Sacramento (left), 23, Batekoo founder, cultural producer and DJ

I come from Nordeste de Amaralina, a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Salvador in the Bahia region.

It’s the city with the highest proportion of black people outside Africa. It’s a place that isn’t reached by politicians: what my family knows about politics and democracy is what the sensationalist media shows on TV.

They don’t engage with politics because they think it can have no positive impact on them. Even so, the reasons not to elect someone with a history of racism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia and intolerance in general, and without any solid government plan, seemed obvious.

The only family member I’ve been able to share my sexuality with in an honest way is my mum. She never made me feel uncomfortable about it and has always been very open to learn. Indirectly, my father showed that he wasn’t happy about the fact I am gay, so I moved away from him about five years ago. The rest of my family doesn’t talk about it and I don’t really care.

Bolsonaro’s dangerous rhetoric isn’t just hot air. Within a week of being elected, he signed a provisional measure that withdraws the LGBT+ population from human rights guidelines. When a president has a homophobic past and defends hate speech and torture, he encourages and emboldens others who have similar prejudices.

With attacks against the LGBT+ community increasing day by day, I founded BATEKOO to try to create a safe space for minorities (those who don’t fit the white, European, sculpted standard) to celebrate their identities and use their art and culture to break down barriers and prejudices.

Although I do experience homophobia regularly — once during carnival, I was attacked for kissing another man — I suffer more with racism. My racial identity is way more stereotyped than my sexuality; I realise I’m seen as a threat because of my colour, my look and my identity as a poor black man.

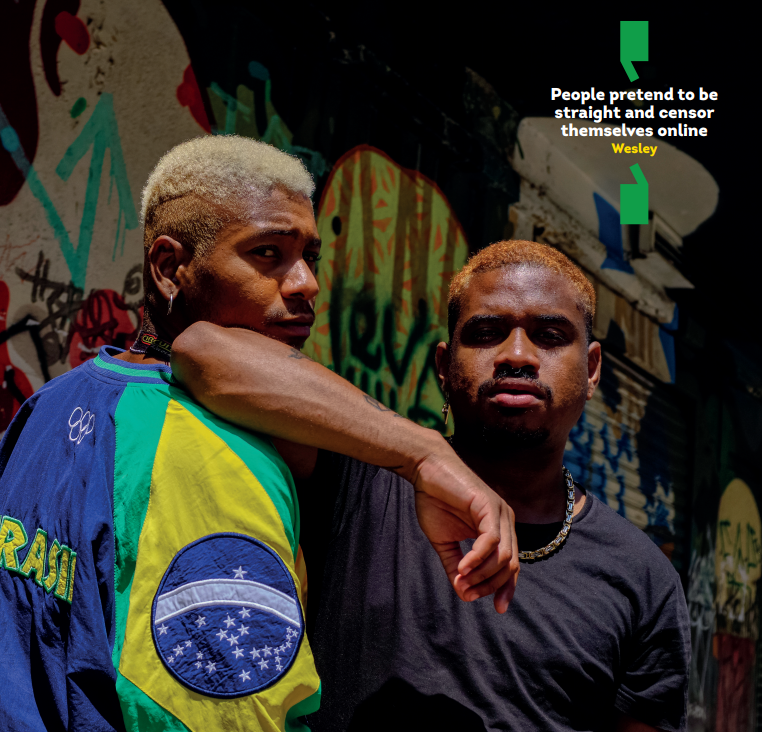

Wesley Miranda (left), 26, art director, DJ and producer

In the past few years, conservatism has grown in Brazil. Several cases of anti-gay and religious intolerance forewarned that Brazil’s future was going to be chaotic.

When people increasingly use religion — Christianity — to justify being vocal against progressive ideas including abortion and [same-sex] marriage, it’s no surprise that someone like Bolsonaro, who offers hope to these majority white and rich people, would win.

I’m out to my family, and my mother hates Bolsonaro. My father though, is a supporter. He’s militant and homophobic, even though he has two gay sons but says he votes for him because he hates PT (Worker’s Party), the rival political party. But I know that he supports a lot of Bolsonaro’s hateful ideas. I’m not OK with that but I haven’t lived with my dad since 2015, so it doesn’t affect me too much.

During the election race, when there was a spike in attacks against LGBT+ people — trans people in particular — a lot of the aggressors were identified as Bolsonaro supporters. They did it to alert the LGBT+ community to the level of violence that was going to be the new norm if Bolsonaro won.

To stay safe, some people have had to pretend to be straight, avoid wearing red because it’s seen to represent communism, and even censor themselves online because people have been hunted down for voicing political opinions.

Like Trump, Bolsonaro has been playing the media and the people against one another, claiming the news is full of lies. His supporters are suspicious of the media and believe blindly in everything he says and does.

But the Brazilian LGBT+ community is strong and unafraid. We have always had to resist — the trans community in particular — so we’re going to continue to do that, by organising ourselves into groups and collectives to defend our rights and to help other groups, such as women whose rights are also being targeted.

Marcello D’Avilla, 31, performance artist

The rage and hatred from mainstream society towards queer people and other minority groups has been going on for years, so Bolsonaro’s win was, unfortunately, not surprising.

Brazil is a nest of fascism, our culture is based on appropriation and it’s a country that is historically subservient to the US. So having a right-wing, religious, intolerant, misogynistic and racist president seems to be a perfect fit.

Half of all crimes against trans people in the world happen in Brazil, but I think things will get worse for the LGBT+ community because the team the president has appointed are all against sexual, gender and identity education, and want to see bibles put in schools. We all know what comes from that.

I define myself as “fag” because gay sounds way too normative. I have my own little company of plays and performances, developing theatrical experiences and video art, as well as hosting sex parties for queer people about themes that are considered sub culture, underground, outrageous and indecent.

I’m proud to be able to hire LGBT+ people and to give them opportunities to resist what’s happening in the political landscape. All of my art projects are connected to the political crisis in which we live. Brazilians don’t know what democracy means and how it could be used for good. Here, it is used as a weapon — and only some can wield it.

Half of the media is paid off by the right, and they pretend that nothing is happening. For years, they’ve supported dictatorships and repressed the left-wing parties and any form of progressive thinking. Instead of the internet serving as a tool to broaden the perspective of Brazilian citizens, it’s become a huge ocean where everybody seems to be drowning in their own lives, feeding off fake news.

To be here and still be able to tell my story makes me one of the lucky ones, and I’m just trying to protect whoever I can while trying to inspire minds, since a lot of us have already been silenced. Bolsonaro’s election will only validate the intolerant views held by Brazilians.

Fascism is here and it’s spreading its wings like an ancient dinosaur.

Lucas Navarro, 29, DJ and performer

Bolsonaro’s victory did not surprise me because the dog of fascism is in heat in Brazil.

Brazilians have always been hypocritical about political and LGBT+ issues. Before the election, people shouted his name on the street, saying “Bolsonaro will kill all the faggots!” I knew he had a chance of winning the election, mainly because a lot of people didn’t turn up to vote.

Even if Bolsonaro’s win doesn’t result in any changes to the rights of LGBT+ Brazilians, symbolically, it can be a threat because his followers feel empowered.

Before his election, minority groups came together in various ways, communicating on social networks, organising protests and campaigning against his candidacy. But during that time, walking in the street at dawn, with our clothes, make-up and attitude, started to feel very dangerous — you become a target for the “Bolsoshits.”

There is hope here in São Paulo though. We have a collective candidacy for state deputy that brings together nine activists from various causes and territories in a single number on the ballot box: to elect not only one person, but a movement.

As of the beginning of this year, the São Paulo legislative assembly, which traditionally is totally straight and mostly occupied by white men, has two transgender women.

Erica Malunguinho and Erika Hilton were elected last year as state law makers. They are the first state representatives elected in São Paulo and bring the power of LGBT+ and black activism to politics.

But even in a city such as this, which is tolerant compared with much of Brazil, people look at me in disgust — or attack me, verbally and physically. Once, a guy threw a plastic bag filled with pee at me.

At other times I’m ignored in restaurants and hotels by staff, taxis refuse to drive me. Almost every day, I’m told: “Die, faggot!” by someone in a passing car. Imagine the discrimination in small inner cities, how much easier it is for LGBT+ people to be massacred and erased there.

We know that Brazil consumes the most trans porn and kills the most trans people. Repressed desire, along with religion and social standing, makes people want to kill their desires — literally.

In a society like that, just existing as a queer person amounts to a military action.