Why are we losing so many gay men to chemsex and suicide?

"Are suicide and drug-related deaths among gay men becoming normalised?" asks social psychologist and expert in LGBTQ+ mental health Marc Svensson

In the past year alone, Phil Gizzie, 40, the director of a smart-tech clothing brand, has lost four of his close friends to suicide or for drug-related reasons. He refers to himself as “a survivor”, having been in multiple situations and circumstances that he says could have prematurely ended his life too.

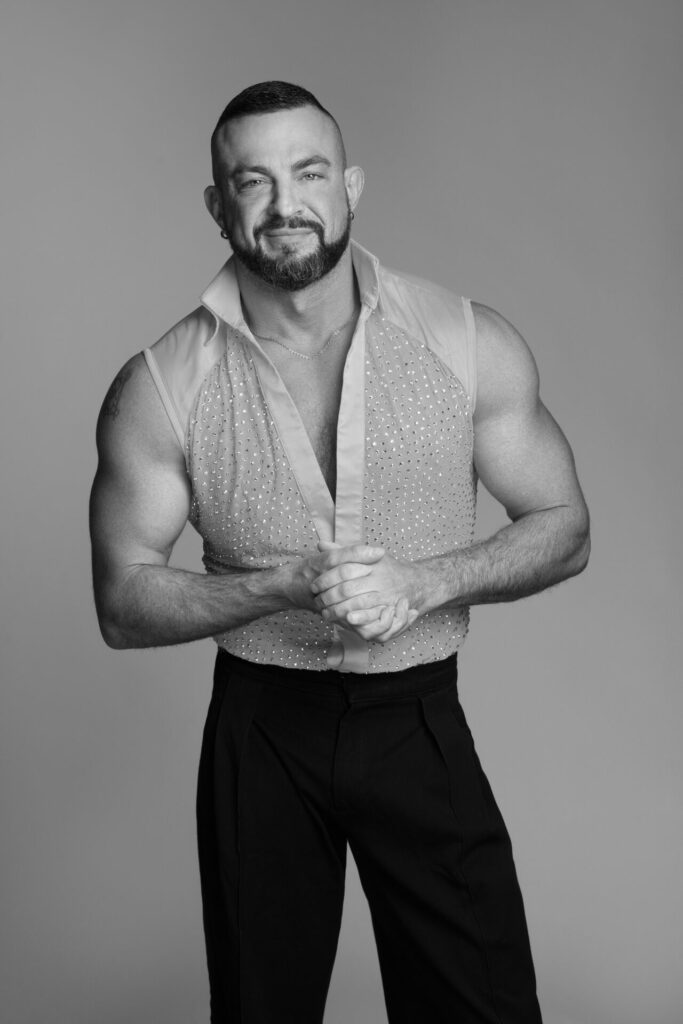

He is not alone in his devastating loss. Choreographer David Allwood, 36, has lost three of his friends in the past year alone — and they were not the first to have died from similar causes.

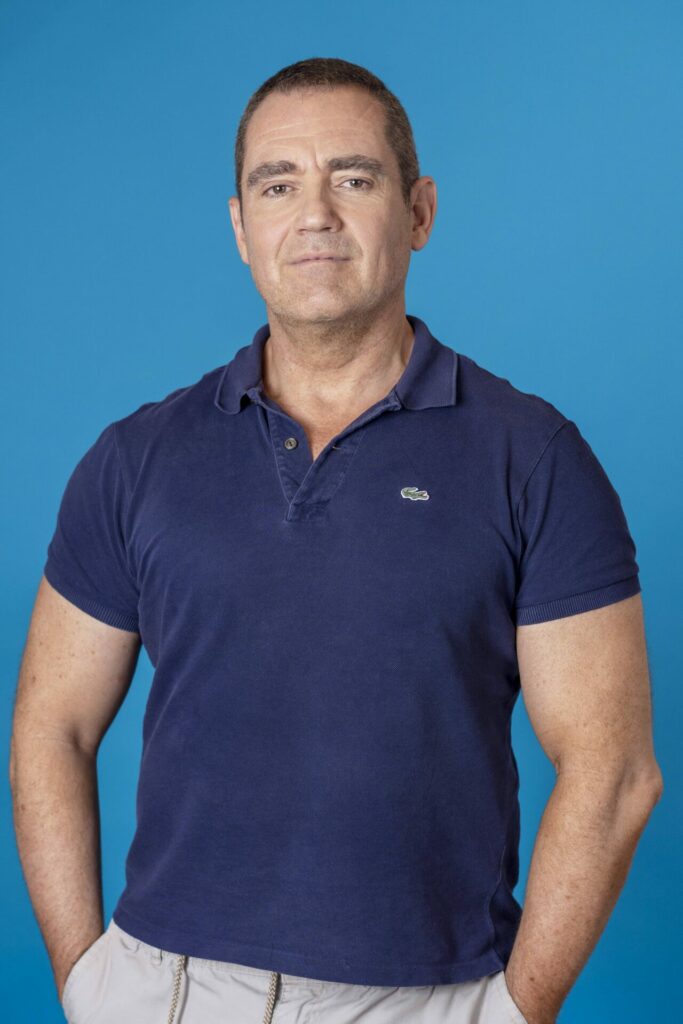

Davide Cini, a digital product manager, 45, has lost two ex-partners to suicide — including Strictly Come Dancing star Robin Windsor in February this year — and too many friends to count whose deaths were drug related.

“Robin was loved and adored by many, but I could see him slowly giving up in recent years,” shares Davide. “Despite our best efforts to show him our love and be there for him, he still felt lonely and that something fundamental to fulfil his need for happiness was missing. He just couldn’t see himself the way we saw him. [He was] chasing an insatiable need to be loved and admired — or perhaps simply accepted.”

“Sexual orientation is not part of the data collected when issuing a death certificate”

That queer people are more likely to have mental health problems and to develop drug addiction and suicidal ideation is well known: an entire social psychological theory was developed to explain it. In 2003, Professor Ilan Meyer, based at UCLA’s Williams Institute, published his minority stress theory. It argues that the difference in mental health outcomes between the LGBTQ+ community and the general population can be attributed to the stigma and discrimination we experience because of our minority identity and status.

Since then, numerous research studies have confirmed the validity of the theory by providing consistent evidence that queer people indeed suffer disproportionately from mental health problems. For example, a recent 2024 global study for the LGBTQ+ business community organisation myGwork, which I led in my work as a social psychologist, found that almost half of the 1,000-plus LGBTQ+ respondents had been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. However, research on the frequency and cause of suicide, as well as drug-related premature deaths in the community, which often also stem from mental health problems, is much scarcer. More needs to be done to uncover the magnitude of this silent epidemic, and for us as a community to better understand what we can do to stop it in its devastating tracks.

The link between the well-established mental health disparities and premature death rates in our community was given some attention in the mainstream press in 2017, when the Huffington Post published a gut-punchingly raw and undeniably accurate examination of what the author Michael Hobbes referred to as “the epidemic of gay loneliness”. He concluded that despite all the progress towards equality and acceptance of gay people that has occurred over the past couple of decades, gay men were still as unhappy, lonely and disconnected as they had been decades before.

The rise of chemsex

Despite greater equality through legislation and visibility in the media, stigma and discrimination had become more subtle, but no less harmful. Plus, the very fabric of the gay scene had been reshaped by a combination of the rise of online hook-up apps and new sex-and-confidence-enhancing drugs. We had never been more connected, yet feelings of internalised homophobia, stigma and shame pervaded among queer adults, to be inevitably projected onto others. This, Hobbes argued, can create a perfect set-up for drug-induced temporary and shallow connections, most often not lasting beyond a drug-fuelled sex session, commonly referred to as ‘chemsex’.

It became more common — and had damaging consequences. Throughout the 2010s, the demand for chemsex support offered by Dean Street, a sexual health clinic in central London, had increased steadily. As did the demand for Antidote, London-based LGBTQ+ charity London Friend’s drug harm reduction support service.

In 2019, Channel 4 broadcast Sex, Drugs and Murder, a documentary produced by Dispatches in partnership with Terrence Higgins Trust. In it, journalist Patrick Strudwick passionately talks about the common use and too-often deadly consequences of the drugs GHB and GBL (commonly referred to as ‘G’) on the gay scene. In 2022, GHB/GBL were upgraded to grade B drugs (arguably, primarily because they had become increasingly used as date rape drugs in straight clubs). However, this did not reduce the demand for it on the gay scene — it only made it more expensive.

In July 2018, the government had published a report on the findings of its National LGBT survey alongside an LGBT action plan outlining how to improve the lives of British queer people. Then, in the spring of 2020, the pandemic hit, and everything changed — for the worse.

The lockdown legacy

The pandemic exacerbated many issues that already existed. Loneliness and isolation became an even bigger global problem (not only for queer men), and our mental health deteriorated.

With social-distancing restrictions in place, Dean Street was no longer able to offer face-to-face chemsex support services. Ignacio, one of its former chemsex specialist advisors, decided to set up the charity Controlling Chemsex, offering online support services for people struggling with their drug use and sex addiction. “People lost their jobs, were banned from socialising, and confined to their homes for months on end, but the hook-up apps were busier than ever,” says Ignacio. “Many men who contacted us told us their drug use became much more frequent during the lockdown, and almost exclusively associated with casual sex hook-ups.”

Some may argue that normality has somewhat returned, but we are still learning about the long-term effects of the pandemic at societal level, as well as in the LGBTQ+ community. Ignacio explains that the demand for Controlling Chemsex services has skyrocketed, and suicide ideation associated with drug misuse is increasingly common.

Julian Dineen, assistant manager at Antidote, tells me that most of their clients are gay men with crystal meth and/or GHB/GBL addiction. “The change in drug use, cost and availability has had a significant impact on our community. Chemsex and addiction does not discriminate; it reaches far and wide and impacts the lives of families and loved ones, as well as the individual,” he says.

Crystal meth can significantly impact people’s mental health, especially if there is already a pre-existing condition. Low mood, depression, psychosis, suicidal ideation and impaired decision-making are just some of the negative side effects associated with its use. “At the same time, GHB/GBL is very dose specific; the margins for error are small and we hear too often about accidental GHB/GBL overdoses.

“It’s difficult to really know what’s going on without data,” concludes Dineen. “We can make estimations. We can go on a feel of what we have experienced, but without the data it’s really hard to know what’s happening and how big the problem is. I certainly have a sense that we’re only scratching the surface when we talk about losing loved ones to suicide or a drug-related death.”

Is it an epidemic?

The short answer is we don’t know for sure because we simply don’t have the data. And that’s a central part of the problem. National statistics from England and Wales tell us that men are more likely to end their life than women, and drug-related deaths are most likely to be caused by opiates, and to happen to people born in the 1970s, living in the north of England. In fact, geographically, London has among the lowest rates of drug-related deaths. But are these national statistics also representative of the LGBTQ+ community? As it stands, there is no way for us to know for certain.

Information about sexual orientation is currently not part of the demographic data collected when issuing a death certificate in the UK. Similarly, GHB/GBL – a commonly used drug on the gay/queer scene – is neither included in standard toxicology reports, nor accounted for in national drug-use statistics. GHB/GBL have been linked to many premature deaths on the gay scene, in both accidental and more sinister circumstances.

The logic for not including these drugs in standard toxicology reports is not difficult to grasp. Only a small sub section of the UK population uses them, and the healthcare system and our government naturally prioritise the drugs causing the most damage across the wider population. However, this leaves the very real possibility that a silent epidemic could be taking place on the gay scene right now, and there would be no way for us to know for sure.

National suicide statistics data comes with a similar limitation in that it does not include information about sexual orientation. It is therefore impossible to know for sure how many more gay/bi/queer men end their lives compared to straight men.

“Each person who tragically loses their life prematurely has their own unique story”

Each person who tragically loses their life prematurely has their own unique story, life experiences and personal circumstances: it’s difficult to generalise. It’s understandable that family and friends might be hesitant to the idea of “reducing” the death of their loved one to a number and a statistic, as a death to be analysed and categorised together with hundreds of other possibly related sudden premature deaths. But it’s important that we do, as suicide and drug-related deaths often share many of the same underlying contributory factors.

The lack of reliable data on the occurrence of both types of premature deaths in the gay community is likely one of the reasons why preventative resources and support is so scarce. If we don’t know the scale of the problem, how are we expected to develop interventions to prevent them? But this silent killer is far too real, to far too many of us.

“Most gay men I know have lost multiple friends”

In the absence of data, we have only anecdotal evidence and research to provide the reasons for an increase in suicide and drug-related deaths in the gay community. Various contributory factors are at play. A lack of self-worth and self-acceptance combined with a sense of loneliness and isolation — a feeling that no one will ever love you for who you really are — are common denominators.

Davide recalls in emotional but determined detail the life and sudden premature death of his ex-partner and close friend Robin Windsor. Well-known to the nation for being one of the staple dancers on Strictly Come Dancing from 2010 to 2013, Robin took his own life earlier this year.

Davide and Robin dated for three years, from 2010 to 2013. Robin proposed to Davide in August 2013, and they got engaged. Davide adored Robin’s caring and loving personality, and says he believes their deep and lasting connection, which continued well beyond their relationship, was largely based on their personal experiences with poor mental health, as well as their shared tendency to care for and support others they could see were struggling with similar problems.

“It all got so much worse after the accident at Strictly”

It was after Robin suffered a back injury on the set of Strictly and was subsequently dropped from the show that he got involved with the mental health charity Sane, for which he volunteered much of his time and energy in the years leading up to his death. He talked openly and candidly about his own mental health struggles, to fight the stigma and to support others struggling. “It all got so much worse after the accident at Strictly,” recalls Davide. Throughout their relationship, sexual intimacy was often associated with recreational drug-taking, to the point where they decided to separately go to a sex and intimacy therapist.

After discovering that Robin never attended the therapy sessions, despite promising he would, and realising Robin was not ready to address his childhood trauma and intimacy issues, Davide called off the engagement later in 2013. They remained close friends until his death. In the years that followed, Robin went to therapy and finally felt ready to meet someone and build a future. He fell in and out of love several times, each time chipping away at his hope of finding ‘the one’ and leaving him heartbroken and depressed for months. Davide says that towards the end, Robin struggled with a sense of purpose in life.

Probing the psyche of gay/bi/queer men, Yale professor and clinical psychologist John Pachankis argues that we experience unique, status-based competitive pressures due to both our social and sexual relationships mostly occurring with other men, who are known to compete for social and sexual gain. He calls it intraminority stress (building on the original minority stress theory) and published a paper with colleagues in 2020 called ‘Sex, status, competition, and exclusion: intraminority stress from within the gay community and gay and bisexual men’s mental health’. It suggested that stress from within the gay community due to its perceived focus on sex, status and competition placed gay/bi/queer men’s mental health stressors over and above those of traditional minority stressors. In other words, the stress we put on each other within the community can cause more harm to our mental health than the stigma and discrimination we experience from wider society.

However, irrespective of our sexual orientation, we are men living in a heteronormative society that from an early age teaches us to be strong and competitive while hiding our emotions. As most queer men don’t go on to form traditional families with children, career and status can become our primary purpose in life. If we then find ourselves not living up to our own — or perceived societal — expectations, we might experience a disproportionate sense of failure compared to men with families and children who contribute to their sense of life purpose.

“I sometimes feel lost and forgotten about”

Life purpose can be a problem in particular for older gay men. Now in his mid-forties, Davide says, “I sometimes feel lost and forgotten about — what are we supposed to do when we no longer enjoy going to parties, clubs, or chill-outs? It’s not what me and my friends want to do anymore, but where are the alternatives?”

David, who was crowned Mr Gay Great Britain in 2022, shares a similar sentiment. “I think many gay men of the older generation feel ignored and forgotten about. Young queer people have got different priorities and life perspectives these days,” he says. “There is a real divide in our community right now, and I think that can be particularly hard on older gay men.”

Having grown up at the tail end of the AIDS epidemic, Phil never thought he would live beyond his thirties. “Gay men died young then, so I assumed I would too,” he says. And perhaps that’s part of the problem. Many of the role models we would have had passed away before their time and left a void behind them. We need to fill that void with alternative queer life course pathways to be inspired by.

Phil’s experience introduces another common cause of poor mental health in the LGBTQ+ community. He came out at the age of 14 to a not particularly supportive family. “I think every gay man that comes from a family that weren’t supportive of them ought to have therapy,” says Phil, who now regularly helps friends going through similar struggles to those he went through.

“The fear of rejection and the habit of suppressing the real you are both incredibly difficult to shake”

Davide grew up on Malta’s second largest island Gozo. He tells me how his dad wasn’t physically or emotionally present throughout his childhood. “Those years of feeling disconnected or rejected from a parent, the people who are supposed to love you unconditionally, will shape how you relate and connect with people as an adult,” he argues. “The fear of rejection and the habit of suppressing the real you are both incredibly difficult to shake.”

These deep-rooted patterns that affect our ability as adults to create, and believe that we deserve, authentic connections and loving relationships can be unlearned. This is what Your True Colours is all about: a wellbeing retreat for gay, bi and queer men which I am involved in, together with Davide Pagnotta, founder and CEO of Wise Humanity. It’s about giving men the tools and knowledge to rid themselves of the shame and help them create authentic connection.

Added to the above factors is a learnt avoidance of talking about our emotional struggles, out of fear of coming across as weak or unattractive, while any sense of failure in our professional lives can become overwhelming — to a point where we might find ourselves turning to unhealthy habits to numb the shame or pain.

“As queer people, we spend the first part of our lives ashamed”

“I think it’s often [about] lacking a sense of purpose, as well as a deep-rooted inability to create authentic connection,” says David, reflecting on the possible reasons why gay men might be more likely to consider taking their own lives or turn to drugs to escape their problems. “As queer people, we spend the first part of our lives ashamed and hiding who we really are, and by doing so actively avoiding authentic connection, only to then spend the rest of our lives looking for approval and acceptance.”

Phil points out that an added factor is the isolation that the alluring big-city lifestyle of sex, drugs, body ideals and sex-focused chill-outs can bring. “London and many big cities are hard places to walk,” he says. “You see people who are around one minute and then they are gone the next, and you think to yourself, ‘Have they done what I did?’ London kind of chewed me up and spat me back out.”

As a fellow professional dancer, David also knew Robin Windsor. “He was a giver and a doer. He was always supporting me: every time I met him, he would give me another [dance] costume,” he recalls. Despite Robin’s giving nature, he did not hide his own mental health struggles, and signs suggest he did struggle with intraminority stress, as likely did ‘Ben’ (not his real name), another friend of David’s who also passed away suddenly and prematurely last year.

“Ben was a complete shock; I wasn’t prepared for it at all. I had no idea and, well, I actually think he had no idea he was at the end of his life either,” explains David. “It was more of an accidental mishap with sleeping tablets as far as I know. He was out partying. Apparently, he was very high, and people were telling him he was not in a state to go home, but he went. And then was found by his flatmate either the next day or the day after.”

David describes Ben as an ‘alpha’, someone who seemed to have everything under control, and wouldn’t be the kind of guy that would ask for help, even if he was struggling. He had his own business and owned properties, and was a charismatic and popular man, who did like “to go all-out” when he partied. “It was a common story amongst his friends that when he did party, he did it in an excessive way and there was no real way of controlling him. If that’s what he wanted, then that was what he would do,” reflects David.

He goes on to talk about a third friend who also passed away suddenly last year. In this case too, David is not sure what the exact cause of death was, only that it was also drug related and almost certainly accidental. “I don’t know the exact cause of death and I don’t really want to speculate; I don’t think that’s fair to do,” he says.

The stigma and shame often associated with these drug-related accidental deaths is a problem in itself, as it breeds an environment in which the subject is silenced and avoided rather than talked about and properly processed. A disconnect between the family’s perception of the life the deceased lived and the life they actually lived might further contribute to a general reluctance to talk openly and honestly about the context in which the death took place, and the underlying factors that might have contributed to it.

“It is impossible to know how many more gay men end their lives compared to straight men”

The underlying factors behind the high number of premature deaths in our community are complex and multifaceted, and there is obviously no simple magic formula to fix them. However, there are things we can do to face up to this silent epidemic and start tackling the issues.

Firstly, we need evidence that an epidemic of premature deaths is in fact taking place. To do this, we need the data relating to these deaths that is currently not being collected. This is what I have set out to do with You Are Loved, a new community interest company I have created to help prevent premature deaths in the community by collecting and analysing premature death-related data, as well as providing a grievance outlet and support service.

Phil wells up as we start talking about his four friends who have died in the past 12 months. “I think that’s part of the problem here. They come too fast, too quick. I haven’t had time to address them,” he shares. “I’ve put them in a box and said to myself I will deal with the grieving when I feel I have the time and the bandwidth to do so — I just don’t at the moment.” Just like David shared earlier, Phil is not sure about the exact cause of the deaths of his friends, just that they were drug related, and not planned. Phil goes on to state what perhaps we all already know too well: “There is a lot more to the full picture than their official cause of death anyway.”

This is what You Are Loved will address. A safe and anonymous database will allow anyone to confidentially log the premature death of a loved one. The register includes questions about the official cause of death as well as the wider context of it, and questions about their mental health, wellbeing and drug use. It also provides a memorial space, where thoughts and memories of the loved one can be shared. The register will ultimately collect vital information that will help provide evidence and direct more resources towards the prevention of further deaths.

We also need to get better at celebrating and valuing alternative/queer life course paths. Straight or queer, those who decide to go down the family path will likely associate that with their life purpose. However, those of us who don’t necessarily want children need to be reassured that our lives can be just as full of purpose and joy through the pursuit of other paths while finding love and belonging in all kinds of relationships, not only by following heteronormative models, or the temporary sense of belonging ‘the gay scene’ might provide.

Creating safe spaces

Finally, we need to create more spaces that encourage these authentic connections, to confront and help eliminate the shame, stigma and fear many of us still associate with our sexual orientation. David started Homoparody to provide such a space for queer people, by running weekly all-ability dance classes and the recording of celebrity parody dance videos. David often schedules classes and rehearsals for their community videos on the weekends, to give members an alternative to partying. “Having a responsibility or a sense of commitment to something can really help take your mind off temptations,” argues David, as he recalls a message he received from a member who said it was the first time since moving to London that he had woken up on a Monday morning feeling that he had a sense of purpose, something to live for.

As gay/bi/queer men, we need to learn to appreciate that there is so much more to us than our looks or careers, and that we deserve to be loved and that we belong. “If I can wish for Robin’s life and death to have a legacy, then I wish that by talking about it openly and honestly, it will help others who might be in a similar situation to see and appreciate their lives from a different perspective,” says Davide.

In his last words, Robin said he wants to be remembered as a good person who brought a lot of sparkle and joy to thousands through his dancing and charity work. “I have no doubt Robin would absolutely love that we share his story, in the hopes that it will help someone out there to not make the same decision as he ultimately did.”

In memory of Robin Windsor, and all the other friends, partners, and loved ones we have lost to premature deaths recently, and over the years

Marc Svensson is a social psychologist and expert in LGBTQ+ mental health. He is the founder of YouAre Loved, youare-LOVED.com, and retreat director of Your True Colours

Need to talk?

National LGBTQIA+ support line Switchboard is available 10am-10pm on 0800 0119 100; switchboard.lgbt

This feature appears in issue 360 of Attitude magazine, available to order now or to download alongside 15 years of back issues on the free Attitude app.