What’s next for ongoing protests outside primary schools? We ask industry experts their views

Parkfield School and Anderton Park Primary School, in Birmingham, are experiencing ongoing protests

By Steve Brown

This article first appeared in Attitude’s June issue 309.

Primary schools in Birmingham have hit headlines after parents pulled their children out of classes and protested against a programme designed to teach the youngsters about life’s diversities.

Although the government then passed new guidelines, there seems to be some troublesome ‘wriggle room’. So, where do we go from here?

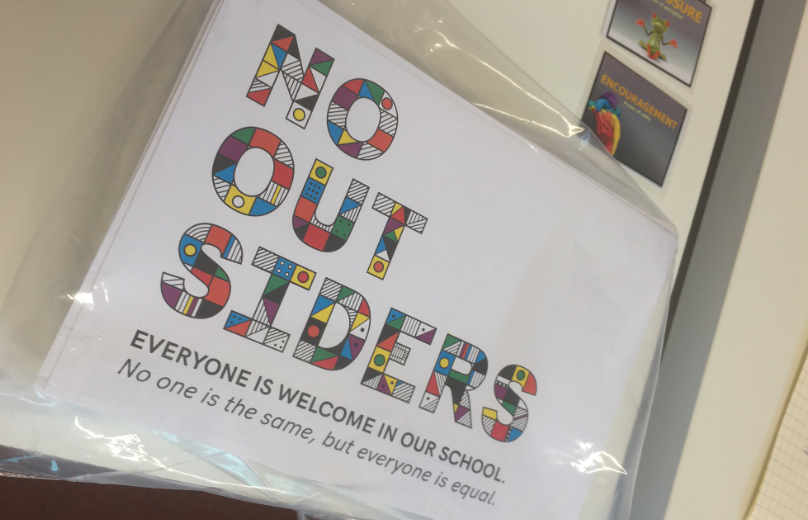

Parkfield School hit the news when parents of children began protesting against the No Outsiders programme — a scheme aimed at educating young people about living in a community full of difference and diversity, whether that is through ethnicity, gender, ability, sexual orientation, gender identity, age or religion.

Parents at the Muslim-majority school argued that the lessons went against their religious beliefs. The protests continued, and debates about whether LGBTQ identities should be discussed in primary schools made national television.

The No Outsiders programme was suspended, and the BBC came under fire for their coverage of the subject, while religious community figures (incorrectly) accused the school of promoting gay sex to children, and nobody seemed to be listening to anybody. Again.

Then, in early April, the Houses of Parliament approved the government’s new PSHE programme, which comes into practice in September 2020, by a huge majority.

However, the guidance in relation to how schools have to teach about LGBTQ relationships is vague, and still maintains they are up for discussion in the context of religious beliefs in faith-led schools.

Anderton Park Primary School has witnessed LGBTQ-allies and other parents being pelted with eggs after showing support for the LGBTQ community and more than 600 pupils were pulled out of the school in protest.

Once again, queer lives are up for debate, and nobody is thinking about the damage this does to young kids who identify as LGBTQ.

We asked people from the community, the scene and those who work in education for their views on how we can move forward progressively, together.

Dr Elly Barnes and Dr Anna Carlile from Educate & Celebrate, a teachers and youth workers charity

It’s unhelpful to talk about ‘debate’ because this implies that people’s identities are up for discussion and challenge.

And anyway, a ‘debate’ between two falsely opposed sides is unnecessary. In our research at Goldsmiths, University of London, we’ve found that schools which take on LGBTQ-inclusive work in a way which is respectful to their whole communities find one thing that everyone can agree on: no religion condones bullying.

The latest government guidance is confusing because the Equality Act 2010 has always mandated this work — in fact, the guidance falls short of what the law requires.

Successfully inclusive schools explain to parents that this legislation requires teachers to help children learn about people of all kinds, including LGBTQ people, people of faith and people with disabilities.

Rather than having a few one-off special lessons, the best way to do this is to weave representation of all these kinds of people through the entire curriculum, with, for instance, images on the walls, and the books available in the library.

This builds a future of inclusion and social justice.

A Department for Education spokesman

There is no reason why teaching children about the diverse society that we live in, and the different types of loving, healthy relationships that exist, cannot be done in a way that respects everyone’s views.

Faith schools can build on the core content of the RSE curriculum, reflecting their beliefs in their teaching, but we expect all content to be covered and have given schools flexibility over how they do this to meet the needs of their pupils.

We are actively engaging with teachers, school leaders, representative bodies and teaching unions to look at how we can best support schools in bringing in the new subjects.

All schools should promote the fundamental British values of democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and respect and tolerance of those with different faiths and beliefs.

From 2020, primary schools will also have to teach about the importance of family, including different family models, as part of our proposals to make age-appropriate relationships education compulsory.

We’ve also made sure there will be time before these subjects are introduced for schools to consult parents on how the new subjects will be taught.

Steve Boyce, from Schools Out

All children, in my experience, grow up with an innate sense of fairness and justice, and as teachers (I am a former primary school head teacher), we constantly hear “that’s not fair.”

No Outsiders explores all forms of discrimination and prejudice in an age-appropriate way through the use of storybooks.

This was summed up for me by one of my grandsons (we have 12) a little while ago, when he asked me: “Granddad when are you going to marry grandma?” (That’s my partner’s ex.)

To which I replied, “I can’t, I’m already married.”

“Who to?” was his instant recourse.

“To granddad John!”

“But you’re both boys!”

To which I replied: “Nowadays, boys can marry boys, and girls can marry girls, as well as boys marrying girls.”

I got the most unjudgmental but considered response of “OK.” Children are not born prejudiced; they are bombarded by societal stereotypes and commercialism.

Asifa Lahore, performer

The government has implemented this legislation into all state schools; Parkfield is a state school regardless of the majority of its pupils being Muslim.

If a child is in a state school, they should be educated along the government’s guidelines.

Furthermore, if an actual faith school chooses to discuss LGBTQ relationships, I believe that there should be appointed members from each respective religion, who are from the LGBTQ community, to provide a curriculum that touches upon religious codes and morals.

I grew up with Section 28 and the last thing I want is for LGBTQ children, of faith communities or not, to experience the hardships I endured because of the blackout regarding being LGBTQ. Let us not forget our history and allow for anything less than equality.

Bae Sharam, activist/performance artist

I firmly believe that allowing any kind of debate on the ‘validity’ of LGBTQ relationships is wholly wrong, damaging and even dangerous — regardless of whether it’s part of a faith school, a state school, or any school.

It continues to perpetuate [the myth] that there are two sides to this conversation, which simply isn’t the case.

I believe that there are core fundamental rights, values and attitudes that are (and should always be) universal in our communities about how we treat other people — and that these values go beyond and override our individual faith system or values.

Continuing to call it a debate, to call it a conversation, to call it an argument, only feeds into the narrative that we are one of two options.

But that’s a false equivalency: there aren’t two options, there are no sides, there is only the universal truth that being LGBTQ is one of the multiple ways that people live their lives.

I’m deeply disappointed in the government for making allowances for bigotry that hides homophobic and transmisogynistic extreme fundamentalism.

But the main thing here is that it’s imperative for people of faith to continue to stand up visibly and vocally for LGBTQ people, and especially for other queer people of faith who will be most marginalised by this ‘debate.’

It’s important for allies of faith and queer people of faith to take control of this narrative and reaffirm that there is no place for a ‘debate’ like this in our society any more.

Shahmir Sanni, whistleblower turned data privacy and LGBTQ activist

In Britain, religious freedom should not impose on the rights of minority groups.

The normalisation of homophobia is a direct result of the British media and politicians seriously putting transgender identity up for debate when it should be treated as just as unquestionable as someone saying they are gay, bisexual or intersex.

However, it must be acknowledged that pink-washing and white-washing are a serious problem when it comes to addressing issues like this.

A lack of nuance in our criticism of communities such as Parkfield School will endanger LGBTQ Muslims in particular.

If you want to address the community-related problems of Birmingham and Manchester, then let LGBTQ Muslims, Jews and Christians (particularly people of colour) do it.

Popular LGBTQ voices should lend support to queer members of these communities to engage in this debate rather than give themselves a platform to slander those communities without actually presenting concrete, nuanced solutions.

Critiquing the Parkfield community with white supremacist rhetoric such as ‘send them home if they don’t like it’ is regressive and endangers LGBTQ Muslims — and I’ve seen too much of this from within our community.

First and foremost, we should be ensuring that LGBTQ Muslims are protected.

Max Taylor, co-chairman National Student Pride

Science proved long ago that nobody chooses their sexuality. So the idea that talking about LGBTQ people at school will “turn” children is — factually — wrong.

Everyone is entitled to their own opinion, but nobody is entitled to their own facts. Primary school is already about making sense of happy, healthy relationships.

With their natural inquisitive nature, children are bound to ask about their uncle’s boyfriend, or mummy’s friend who is married to her wife.

What is not ‘age-appropriate’ about these questions? So, it boils down to an issue of continuing religious intolerance towards LGBTQ people, and we have to take the first step towards healing that.

We started National Student Pride 14 years ago to help close those divides, in response to a homophobic and religious hate preacher’s speech on campus at Oxford Brookes University. And the way we need to do that is by reaching out and having conversations.

There is no debate to be had on our identity, but I start every day ready to have a conversation that will help cure ignorance and prejudice about our lives.

Angela Rayner, shadow education secretary

We have a moral imperative to ensure children receive LGBTQ-inclusive education in a society that is underpinned by equality, tolerance and respect.

Now that parliament has passed this new guidance with an overwhelming majority, the government must fully support teachers in delivering it.

There can be no going back to the shameful days of Section 28, and it is now up to the government to provide schools and teachers with the resources they need, as well as showing political and moral leadership, so that this guidance is properly implemented and not undermined by budget cuts.

Throughout this process, Labour has been absolutely clear that there can be no compromise when it comes to our duties under the Equalities Act 2010.

I will hold the government to account, to ensure that they stick to their word and we see LGBTQ-inclusive lessons successfully delivered in our schools.

Sue Sanders, professor emeritus, Harvey Milk Institute, and founder of LGBT History Month UK and The Classroom

If schools had taken seriously the public duty which has been in force for more than six years, we would not be facing this problem.

Schools OUT UK offered a very effective and simple model for teachers to “usualise” LGBTQ experience and issues and the model can be easily used for all the protected strands.

At the-classroom.org.uk we have provided more than 80 free lesson plans that cover the whole curriculum and are suitable for all ages. The concept is a simple one: when we ‘usualise’ something, we acclimatise people to its presence and take away the threat of difference which creates fear and discrimination.

‘Usualising’ in schools has more to do with familiarising learners with a subject’s every-day occurrence or existence rather than an in-depth understanding of the subject.

To educate out prejudice we need to enable learners to see the reality of other people’s existence, thus countering stereotypes they may be presented with later [in life].

We urge teachers to be facilitated to use this method for all religions, ethnicities, gender, ages and abilities.

In this way, no one group would feel that other people are getting special treatment and would recognise that the school is following the law and enabling its learners to recognise the diversity of the country they live in.