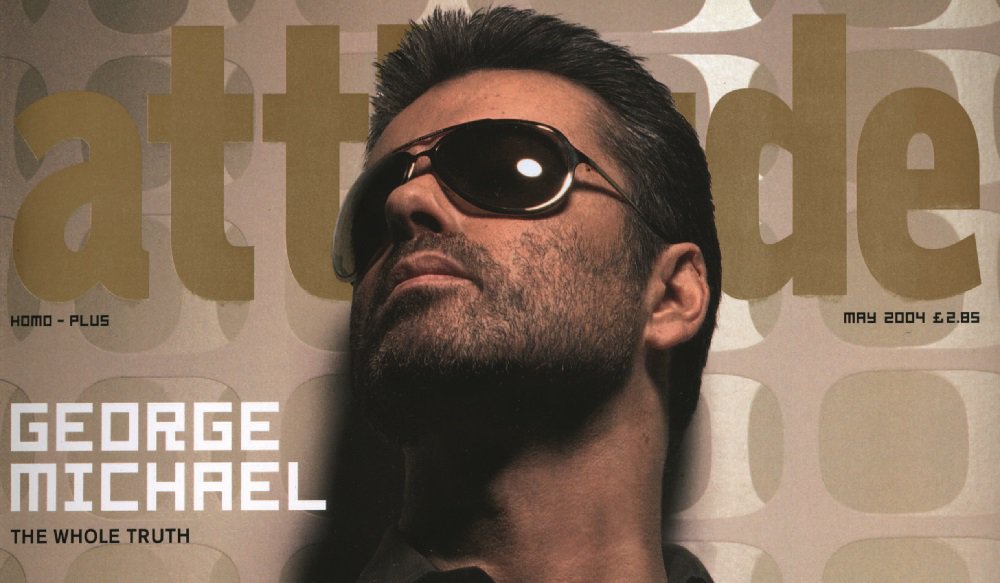

From the archive: George Michael’s candid 2004 interview with Attitude (Part 1)

"I've told you more than I told my therapist in a decade."

By Will Stroude

As the world honours the late, great George Michael, we’re serialising the star’s Attitude cover profile from May 2004.

Typically forthright, the ‘Outside’ singer spoke to us about everything from the closet and celebrity culture to open relationships, New Labour and cruising. Check back every day this week for a new instalment in this frank and unflinching five-part series which captures the sparky, plain-spoken spirit that made George Michael an inspiration to so many, both gay and straight alike.

This interview first appeared in Attitude issue 212, May 2004.

Words by Adam Mattera.

George Michael: Days Of The Open Hand

After years of creative statement, personal tragedy and media derision, George Michael has returned with the most intensely personal and emotionally complex album of his career. Attitude meets the superstar who has no time for anything but the truth.

If you want to know something about George Michael, pop into his local gents. The one in his management offices, tucked away in a quiet side street of an understated, posh suburb of North London.

Hanging above the loo is a silver framed plaque commemorating the two million copies he shifted of his double-decade spanning career retrospective ladies & gentlemen (the title of which, given his sexual history, was always something of a masterstroke of iconic cheek).

On the opposite wall is a discreetly framed plaque casing a brightly coloured packet of instant soup from a continental supermarket. A laughing chicken is emblazoned on it bearing the legend ‘Le Coq’.

It’s a playground double-entendre, but for all the brow-beating seriousness that’s been projected on Michael, by others and himself, it’s been easy to forget recently that he in possession of one of the sharpest wits in the business.

It’s a quality – along with his renewed, almost evangelical, sense of honesty – that has stood him in good stead in the years following that visit to another lavatory – the one in LA in 1998 – and his subsequent, very public, coming out in the media around the globe.

Both his Parkinson confessional and the outside video were genius displays of ‘hands-up, gov’ candour, tempered with some good old fashioned cheek. Both kept the hearts of the British public through his most public strays from the dull, stage-managed celebrity norm that has come to mark our times. They’ve every reason to stay with him.

Growing up with the fresh, youthful motifs of shuttlecocks and poolside margaritas in his Wham! Heyday, he may not have been prolific in his output since, but he’s never been less than sparkling, a diamond in the drudge of our current pop malaise.

That other George, the Boy, may have once said ‘I think George Michael’s lost his sense of humour’ – a quip that Michael himself laughingly reminds me of at one point during our conversation – but the truth is, even in his darkest hours, it never really went away.

“As you know, I wanted to do this interview a couple of years ago when I really thought the album was going to come out,” says Michael as Attitude settle on the lush couch in his office suite, surrounded by ephemera from his lengthy career (Attitude blushingly admits to gleefully spinning around in the Fastlove chair moments before George’s arrival).

“So, sorry for the delay – I kinda got side tracked,” he grins, aware of the understatement. A stultifying period of writer’s block and the media savaging of his anti-Iraqi invasion stance, a good year before they themselves caught the wind of the public mood (these days, it seems popstars must be seen and not heard), is now well and truly over.

Amazing was his most unashamedly joyous single in years. And the album, Patience – an emotional tour de force – broke his own personal record for first week sales. So he has every reason to be on buoyant and compellingly good-humoured form. He got his last laugh, you see. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you George Michael…

It’s great that you’re back, talking to the media again. There’s always been this weird contradiction about you – on one hand you’re seen as this reclusive figure that never goes to celeb parties and hides from the press, and yet you’ll phone up The Richard and Judy Show or do Who wants to be a millionaire with Ronan Keating. How does that work?

I quite like that. Basically, I just do whatever I want to do. I don’t like being in telly, but I always wanted to be on Who Wants to be a Millionaire. I thought it would be fun and I’ve often said so when I’m sat there watching it with Kenny. I was having dinner with Ronan, who I’ve known for a while, when I decided to do it. We both lost our mums in the same year and he was doing it for his mum’s cancer charity. So I offered to join him, and Kenny nearly choked on his steak. I thought it’s a perfect excuse and it’s not going to hurt me, either. My manager was like ‘What the fuck is he doing?’ but I knew people would see it in the right way.

Is it part of your new freedom?

I can’t be bothered with being aloof anymore. I think being aloof served me very well, especially in that period when my life was a fucking nightmare, when Anselmo was ill [Feleppa, George’s late partner] and my mum died and everything. Not anymore.

You’re stilled very removed from the whole Heat celeb culture of today though.

I don’t think I would have ever been part of that. I always wanted to be famous for being good at something. I wanted to be so good at something that I would be untouchable. Most stars started out as children that felt out of control or oppressed and wanted to show the world and their parents that they were worth something. There are so many people out there now that are prepared to sell their lives to make themselves famous, and that makes them completely vulnerable. I’m not saying it’s right or wrong, I just don’t understand it.

Your singing’s really strong on Patience.

There is something about the vocals on this album that’s a lot more confident, more certain. Even though I love Songs From The Last Century and Older, there’s an energy level to this record that I haven’t had since before all the shit started, before I met and lost Anselmo and my mother died. If you think about the energy of freedom on Listen Without Prejudice, I don’t think I had that energy to give again until last year. Which is why Amazing reminds me of Wham! More than anything I’ve done. The work I’ve done over the last twelve years might have a certain intensity or depth, but nothing has had the energy of the earlier work. I think it’s come with the relief of feeling good again.

This is the first album of all new songs you’ve released since you came out. Was that a pressure, the need to be more honest?

No, it didn’t feel any different, really. Cause if you think of the way I wrote some of the songs before… I’m sorry, but Jesus is a male gender term. ‘You smiled at me like Jesus to a child,’ you’re talking about a man for fuck’s sake! The way I wrote was gender specific in a couple of cases. And a couple of the covers I made male gender specific, with those I was just having a chuckle about it, really. I didn’t really think about it. Like American Angel in the new album. It only occurred to me afterwards that it’s ’he’ all the way through that song and I thought ‘oh god, Sony will probably have a problem with that.’ Well fuck it then, it can’t be a single. I’m certainly not going to change it.

I thought it Older was about grieving and loss, Patience is more about redemption, coming out of the darkness and trying to make sense of the past. There’s still quite a lot of darkness there too, though.

It’s kinda very light and very dark at the same time. There are proclamations of love that I’ve never made before – certainly since Wham! – and then there’s going further into the truth at the same time, like on My Mother had a Brother or Through – they’re trying to get closer to the truth.

I think that song, My Mother had a Brother, has to be amongst the best you’ve ever written. How fictional is that lyric?

It’s not fictional at all. I didn’t know of the existence of my mother’s closest sibling until I was 16 or 17, because he killed himself. He killed himself within 24 hours of my birth, and the tragedy of that, the idea of wanting to leave this world and at the same time not wanting to because it would spoil the pregnancy of you sister… it’s just horrible, beyond horrible. And my mother told me she thought he was gay. They had a very difficult childhood, a dark childhood, and for some reason she didn’t think it was appropriate to talk to us about it until we got to a certain age. It’s a tragic story about how much more difficult it must have been as a gay man in the 1950s. If he’d held on and beaten his depression for long enough, he would have seen the changes in life that would have made him at least a happy middle-aged man.

Do you think that affected your mother’s relationship with you and your sexuality?

It must have done. How can she not have been worried by my sexuality if her brother’s sexuality killed him? When you put your family tree together you understand so much more about who you are. Sometimes I felt that my mum made me feel that I wasn’t manly enough, or boy enough, when I was growing up, which was so out of character for her, because she was such a great mum, and so liberal in her attitudes. And that song is disguised as asking my mother to tell my uncle how much life has changed and that I live a happy life as an openly gay man and I have loads of sex and it’s great. But really in a way I think I’m trying to tell her that I forgive her for that.

You came out to your mum relatively late.

I came out to my mum and dad when Anselmo died. Although my mum always knew.

Because she’d met him, right?

Er, did she ever meet him? No, she never met him. I was getting confused with someone else she met that I was in love with. I remember him telling me ‘the way your mum looked at me – she absolutely knows.’ Cause it was a ‘don’t hurt him’ kind of look. And as it happened that bloke did really hurt me. But I knew she knew, because the two years that I was living in LA with Anselmo she never picked up the phone and called me once. And that for her that meant ‘well, if he wants to tell me he will, but I don’t want to have someone else pick up the phone on the other end and then pretend that I don’t think it’s odd.’ This is something else that’s very important to my particular story, and that’s that my coming out was not… I won’t go further into it than to say that within my family, it was not coming out that I was afraid of, or thought would be dangerous, because I knew my mum would absolutely be fine with it.

And my dad, I’ll be honest with you, even though I cared it wouldn’t have been a deciding factor. Maybe I didn’t care enough. My relationship with my dad is not that way. The honest thing is that actually it was about being the first member of the family to be openly truthful. We’re just one of those families. I was afraid that it would be explosive in my family. And it was explosive, but that had nothing to do with my sexuality. It was just everybody having to grow up and deal with what really happened in our childhoods. I’ll never regret it, even though it wasted years of my life in certain ways, I wasn’t wrong. I was very scared of it for certain reasons and I turned out to be right. But it goes some way as to explaining why I should be keen to imply in every other way that I could to the public that I was gay without actually saying it. And your desire to be famous was all tied up with what happened in your childhood? My childhood was oppressive which is why I wanted to do this, sure. It’s an old cliché but children who don’t feel heard always want to sing or perform or do something that makes them look as if they have a right to exist. I suppose having felt oppressed by my family life, then by my own response to my sexuality and then by the media’s response to my sexuality, I’m just so sick of all that ‘keep your mouth shut’ stuff. Having a big mouth might make things hard, but it doesn’t make things any harder than being closeted.

Read all five parts of George Michael’s May 2004 cover interview here.