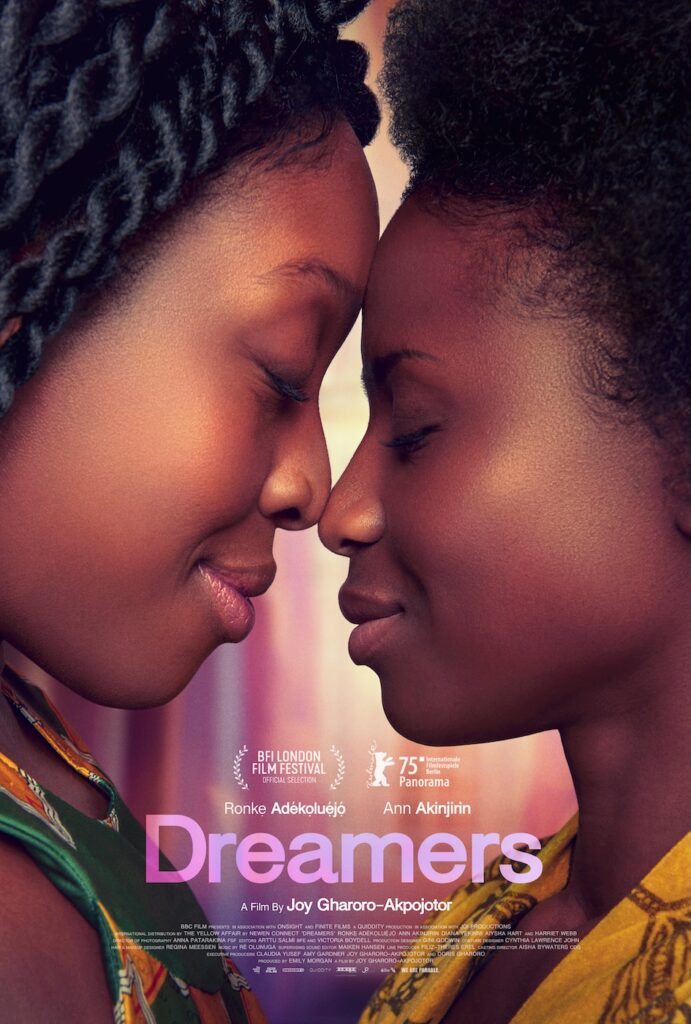

Dreamers director Joy Gharoro-Akpojotor on bold new romance film: ‘Queer immigrants are like: I feel seen’

"It's a version of me in an alternate reality," says filmmaker Joy, who here answers questions from cast members Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo, Ann Akinjirin, Diana Yekinni and Aiysha Hart for Attitude

This week sees the release of Dreamers, new queer love story film set in an immigration detention centre.

The film stars Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo as Isio, a Nigerian migrant who has been detained after living undocumented in the UK for two years.

While awaiting the verdict of her asylum plea, her friendship with charismatic roommate Farah (Ann Akinjirin) evolves and deepens.

As her faith wanes as her asylum pleas are rejected, Isio must choose between compliance and the risk of escape in pursuit of true freedom.

Here, Dreamers director Joy Gharoro-Akpojotor answers questions from cast members Ronkẹ Adékoluẹjo, Ann Akinjirin, Diana Yekinni and Aiysha Hart about this critically acclaimed, semi-autobiographical new movie.

Ronkẹ: What excites and terrifies you the most about being an artist?

What excites me the most about being an artist is that I get to create and I get to make up stories. It’s great because as a kid you have make believe and you make up stories when you’re younger and suddenly as an adult I get to see those stories come to life. So that’s quite exciting. I remember my first book. When I was 11 I wrote a book, it was called Vampire Busters. Because I was like, I want to do the Ghost Busters but with vampires. It was like a little notebook that I actually don’t know what it’s about. I think my mother still has it. But I was like, I imagine if I got to make that as a film, that would be fun.

What terrifies me the most? I mean, people will judge my work. I mean, if anyone saw the Vampire Busters they would judge my work. But I think art is meant to be judged, challenged, criticised. That’s sort of the way it is. But I think that’s the most terrifying thing. That when you send the work out into the world, people bring their own baggage, their own anything. And you have no say and you can’t explain yourself and you can’t be like, ‘no, but look at it, this will argue your way through it.’ That’s hard.

Ronkẹ: If we had the time and money to make a three-hour long feature, what would you have magnified, extended or expanded on?

I would have put a break in the middle [laughs]. Make it, like, three hours with a break, because I hate anything over two hours. But what would have I expanded on? I think, oh my goodness, more love. I would have given them a longer love lead up. I would have given more friendship stuff. I think I would have still got rid of Farah at the same place. I would have… I think I would have gone more into each person’s story and each character’s life in the removal centre. I would have done a bit more of that.

Maybe at the very end when Isio is caught, I would have probably also followed Nana and Atefeh’s character out in the world. Because one of the things, when we first had rehearsals, everyone was like, ‘what, they just run away and leave her? They don’t go back?’ Maybe in the three-hour version, we would have seen them running through the fields, forests, wherever they are, with the cows and goats. And then they would be like, ‘oh wait, where’s Isio?’ We would have turned around, and then they would have tried to go back, but then realised they don’t want to go back. It would have been a whole thing if we could make a three-hour long film. But yes, that’s probably what I would have done. I would have made it a whole three-hour odyssey. Also, if we had money, I would have done some stupid, ridiculous crane shots, because we can. And maybe have a crane we rarely use, some drones, just because we can.

Ann: How have you found bringing such a personal story to the screen and to a wide audience?

It’s been great. It’s been nice. Although it’s a personal story, I think a lot of people find various parts of themselves in it. They bring elements that I didn’t know would touch people. And I really have to remind myself that I think, as people, we all share similar emotions. And I think what’s been nice is seeing people feel throughout the film. They go from laughter, to crying, to laughter, to crying, to annoyance, to anger, to more crying. And that’s nice. I think that’s been a joy to watch, generally. I think for me, my aim is at the end of the film, people walk away with lots of feelings that they have to go off and process. Because I think when you go through the system, that’s also what’s happening to you.

Ann: Were there any boundaries that you felt you needed to put in place?

Oh, for myself, yeah. I had a therapist every Saturday. Because I think I had to remind myself that even though it’s a personal story, it is not my story. Well, it is my story, but it’s not me. There are elements of me on screen, but that’s more about me having to sort of take myself out of situations. But also, being a director is also a producer.

I did not ask any producer questions throughout. Unless it was brought to me. So, I made a point of not going into the production office. Because I have a habit of going in and being like, ‘what’s the budget saying?’ ‘Where are we at with this and that?’ So I was like, I can’t do that.

So that was something that I had to really be like, you know, especially if I overhear somebody complaining about something, I’m like, whose job is that? It’s like ‘Joy, mind your business. Mind your business.’

Aiysha: Dreamers is semi-autobiographical for you. What’s it like to direct a lead performance when the character is essentially you?

Such a hard question. I mean, I think in directing Ronke I wasn’t thinking she was me. I was like, I had to learn how she needed to be directed. I was very much leaning towards her finding the character for herself.

We had two weeks of rehearsal where it was more about her being able to find the character that we were happy with together. I didn’t want her to be like: ‘Oh, Joy, this is you, I’ve got to be you.’ It’s more about, this is a version [in my mind]. It’s a version of me in an alternate reality. And in that reality this is who this character is. And these are the decisions that she makes and there are bits of me in that person, but in this reality that’s not me. It’s hard to think about it, but I think Ronke really found a way of finding herself in the character and being able to bring the character to life where I didn’t particularly always see myself in it. I mean, there are elements of her journey that I see in me, but I think in terms of her, the way she portrayed the character on screen, I think I got distance enough because we had that time to just rehearse.

Aiysha: What has been the most rewarding part of telling your story, and has it in any way helped you process the past?

The most rewarding parts of telling my story has been how it’s touched other people. I went to a film festival in Amsterdam, and we had a panel, and they had brought these asylum seekers, these queer asylum seekers. Three of them. We had this panel together, and afterwards they watched the film. One of the guys got up and gave me a hug. He was just like: ‘I’ve never seen myself on screen in that way’. And I think that’s the reason why I wanted to make the film, is for that reason. Where people can watch it and be like, ‘somebody sees me’.

It happened [when] I was in Copenhagen, something like that. This guy watched the film and was like: ‘I was slightly triggered, but in a good way’. He had been through the system, was talking about [how] people don’t understand what it is that you go through. Watching the film, it just shows that somebody understands how they feel. And for me, that’s been one of the most rewarding things, is that having queer immigrants come up and just be like, oh my god, I feel seen. That’s been the most rewarding thing.

It’s helped me process my past. When I was making the film, I was always a bit like… Because you know your experience is so singular to yourself, you always wonder if anybody else feels the same way. You kind of have this, like, slight impostor syndrome, because when you make film or you make art, people think you’re speaking for, I don’t know, an entire community.

I think having those experiences with people, it also makes me feel like: ‘Oh, I wasn’t [alone] – there was multiple people going through this. Not just in the UK, but in other countries. It sort of makes you feel like you’re not alone. Even though they’re there and I’m here, it just makes you feel like you all exist in this sort of like bigger world bubble, but in different places. You’re having this shared experience that you didn’t realise was possible. But in a way it makes you feel less lonely.

Diana: If you had a superpower, what would it be and why?

Do you know what, if I had a superpower, it will be like storm. To change the weather. Because I just need more 20-25° weather to thrive at my best capacity and I am tired of waking up and it’s grey. Or it’s snowing or raining. I need, like, a weather-changing superpower is what I need. I would just like fly in the sky and do something really quickly, and there’s no more raining.

Dreamers is in cinemas from 5 December 2025.

Subscribe to Attitude magazine in print, download the Attitude app, and follow Attitude on Apple News+. Plus, find Attitude on Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, X and YouTube.