Two of the UK’s longest-working HIV campaigners have been awarded OBEs

Dr. Rupert Whitaker and Martyn Butler helped set up and run the Terrence Higgins Trust following the death of Terry Higgins in 1982.

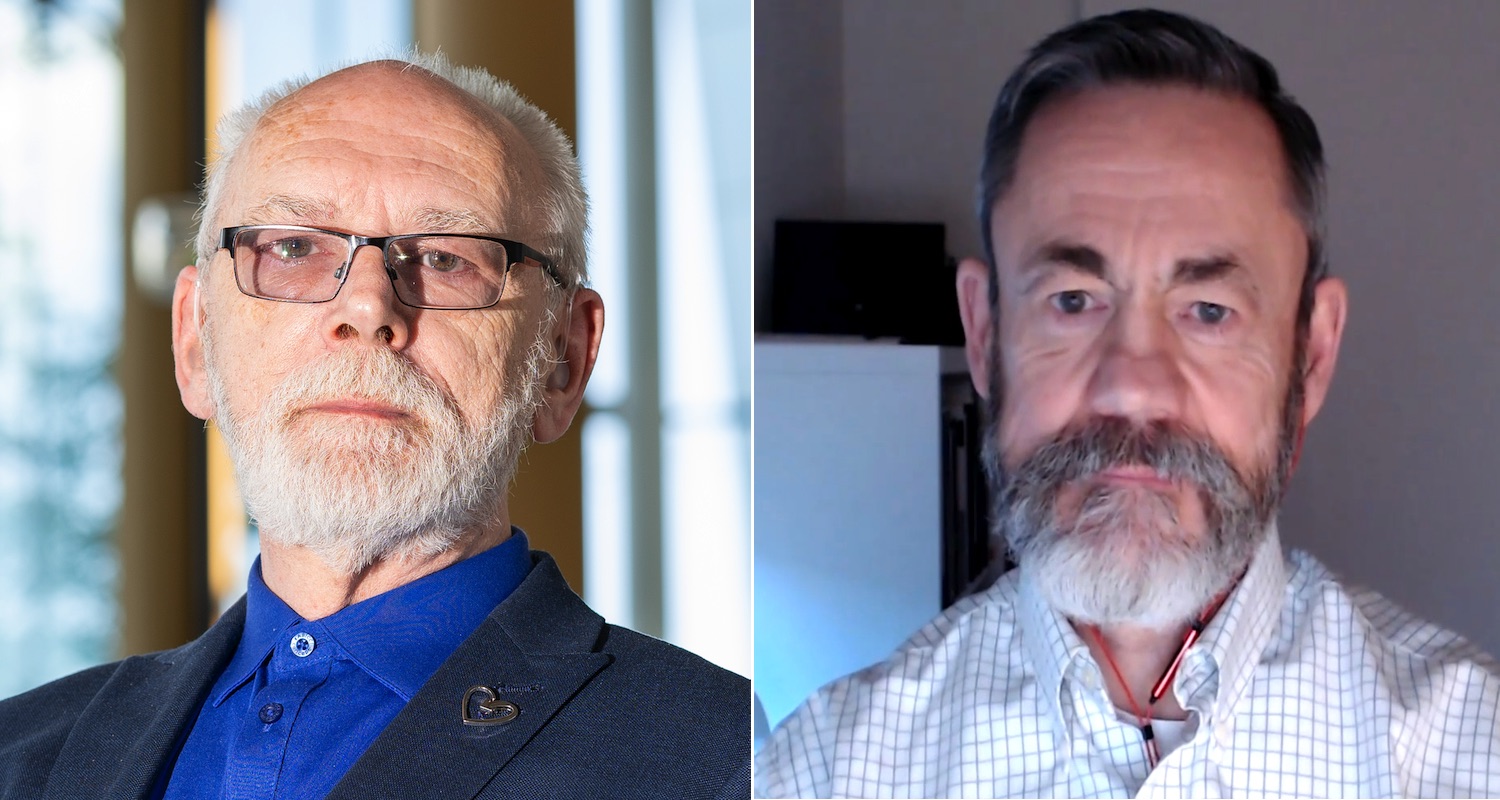

Words: Alastair James; Image: Martyn Butler (left) and Richard Whitaker (Ieuan Berry and YouTube)

Two of the UK’s longest-working HIV campaigners are being awarded an OBE for their work in fighting against HIV and Aids.

Dr. Rupert Whitaker and Martyn Butler helped found and run the Terrence Higgins Trust following the death of Terry Higgins from an Aids related illness in 1982. They’ve been awarded an OBE each for Services to Charity and to Public Health.

Rupert, who was Terry’s partner and is HIV-positive himself says: “I hope it encourages others to continue to stand up and try to make a difference where they see a need and to value everyone’s efforts to create inclusive change.

“Though there are far too many divas, real heroes are rare, so I’m accepting it in recognition of the work that many, many of us have done over the years and, though crucial, often remains unnoticed or unvalued.”

Martyn Butler adds: “I would like to dedicate this honour to all of the millions lost to HIV, including my dear friend Terry who we lost forty years ago. After Terry died we knew we wanted to do something to help others and stop more people from dying like he had.

“I’m deeply proud of the legacy we have given him and for Terrence Higgins Trust’s role in this country’s HIV response.”

Martyn Butler

Martyn was a friend of Terry’s. The two bonded over their shared Welsh-ness and working in London’s nightlife scene back in the 80s. They first heard of what would go on to become HIV and Aids through the pair’s connections with America.

“Very quickly, I started scanning the scene looking for any organisations or groups that might have an insight into this thing. And when you’re looking around for people to do something in life, and you’re the only one stood up, then it’s you. And it was as simple as that.”

Martyn admits that he was naive in those early days thinking it might be easy to contain. However, we know from more recent examples just how hard it can be to contain something like a virus.

He began distributing pamphlets in gay bars, trying to spread the word. The reaction was often hostile. Martyn’s experience was used as the basis for a scene in Russell T. Davies’s Aids drama, It’s A Sin.

“It was actually quite violent. They threw me out of the place and my leaflets after me. In the show they make the guy feel uncomfortable and tell him to go. But the level of aggression was vastly underplayed,” he says.

Martyn Butler (Photo: Ieuan Berry)

Being attacked by the media was one thing, Martyn shares. Being attacked by his own community was difficult. But he says Terry taught him a valuable lesson.

“The greatest thing Terry taught me was how to tell people to fuck off. I’d never been able to tell anybody to fuck off in my life. But suddenly it was liberating.”

Following Terry’s death in 1982, Martyn was among the founders of the Terrence Higgins Trust. The early days were tough. It was hard to get financial or legal support for a charity fighting a disease that was seen to mostly be affecting gay men.

“At every level, we were hated. You picked up the newspaper, we were hated, you turn on the television… There was so much bad stuff coming from every direction. And it wasn’t much better from some of the gay scene either that’s for sure.”

The NHS wasn’t much better either, Martyn tells us. He recounts visiting one friend in hospital who was having his food slid under the door because no one wanted to go near him. When Martyn visited he was given protective clothing to wear, which he likens to a spacesuit.

“I put all the gear on and go in. Then I proceeded to take it all off and sit on the bed. The doctor and nurses were screaming at me, but it was me mate. I was sat in his front room two days before holding his hand. They were bastards, you know. He died very, very quickly afterward. And I’m not sure whether some of the psychological things that people suffered, didn’t add to their speedy demise. They certainly didn’t go with dignity.”

After that, Martyn made a promise that no one would have to go through HIV alone.

And while he’s proud of what the Terrence Higgins Trust has gone on to do over the last 40 years, including campaigning for access to PrEP, education programmes, and proper funding for HIV services, Martyn wishes he wanted to close the organisation down.

“There’s nothing sinister in that desire. It was purely a case that when would I know that we had been successful. When we’re not needed anymore. That would be fantastic, to close it down, and give the money to children or whatever. If we didn’t need it, how wonderful that would be?

But looking back also brings back the memories. Good and bad.

“I still bear the scars. I can look back and say, ‘Wow, I’m glad we did it.’ But there were just so many people I thought I’d grow old with that I had genuine friendships with people I loved. Every one of them gone. That is hard.”

Dr. Rupert Whitaker

Rupert was Terry’s partner before he died. The two met in 1981 just as Rupert, then 18, was about to go to Durham University after living in Germany for a year.

Terry was a “very nice, kind, person, and a good sense of humour, and also very affectionate,” says Rupert. Terry also had a naughty side too. “He and I just sort of enjoyed each other for who we were,” adds Rupert.

The two navigated their relationship as Rupert studied in Durham and Terry worked in London. Rupert would come down for the holidays. In the meantime, they would write to one another, letters that Rupert still has today.

Following Terry’s death on 4 July 1982, Rupert threw himself into the fetal trust in Terry’s name. He also remembers the difficulty in getting funding or other administrative and logistical support.

Yesterday, I received a Doctor of Science (hon. causa) from @RoyalHolloway U. London, in recognition of ‘my contributions to science and patient-advocacy’. As an alumnus also, it was a great honour. I look forward to working closely with the university and students in the future. pic.twitter.com/fwKxims15c

— Dr. Rupert Whitaker (@RupertWhitaker) June 23, 2021

A lot of that, says Rupert was down to classism.

“The information we got is, ‘you’re gay, none of you is the sort who would be associated with running a charity. I wrote to Terry’s consultant, Thomas Cranston to say, the Charity Commission is requiring us to confirm that if we want to name this charity after Terry, and the charity is going to be about this, then we need to have it in writing that Terry died of this disease.

“And Cranston was really snotty. He said: ‘You’re not family. I can give you that letter, once you’ve got this charity set up. So put us in a catch-22. It was really unhelpful.”

But getting volunteers on board wasn’t difficult at all. Once information began to trickle out, things began to snowball. “The problem was knowing what to do,” admits Rupert.

The first thing they did was set up a buddy system so people had someone to talk to. The charity also began creating educational resources to get people to modify their behaviour.

“Some of the early stuff was trying to support creative sex around fetish and BDSM to encourage people to explore sex in ways that didn’t involve the transmission of bodily fluids.”

The NHS’s attitude changed when people started “dropping like flies”. After that, the NHS was more willing to engage with groups like the Terrence Higgins Trust. Another problem at the time was skeptical members of the LGBT community who peddled wild conspiracy theories such as HIV was engineered by the government to target gays.

Rupert believes that part of the reason for the hostility the charity and those fighting against HIV got from the gay community was the liberation that had been hard fought for (“And I was all for that, obviously”) but also fear.

“People did not know how to cope emotionally with this stuff, with this information, and what was happening. Especially as people were dropping like flies. You’d see somebody in a club, and you’d have a great chat with them. And suddenly three weeks later, they’re dead. And this would happen again and again.

“It’s hard to express the effect on the community that that had.”

It’s 40 years since the death of Terry Higgins and the formation of Terrence Higgins Trust—that’s four decades of HIV activism.

Join us on 24 May for an exclusive online event to launch our new strategy and discuss the vital work ahead of us⬇️

— Terrence Higgins Trust (@THTorguk) May 11, 2022

A lot has changed in the last 40 years. One of the changes Rupert has ben most glad to see is an end to competitiveness between organisations tackling HIV and Aids.

“Competitiveness is toxic to success in this field. You still get it, particularly amongst certain activists, and it is toxic. It’s about access to resources, status, and being noticed. But what happens now is that there’s a much greater collaboration between organisations, because we know that no one organisation can do what’s necessary. And this mutual support has meant that there’s a lot more effectiveness.”

In December last year, the UK Government committed £20 million as part of its HIV Action Plan which will include opt-out testing for HIV in A&Es in areas of a high prevalence of HIV. All of which wouldn’t have happened without people like Rupert and Martyn.

Ruper is also convinced that without the fight to get HIV and Aids taken seriously, we wouldn’t have things like gay marriage.

“We had to make connections with people at all kinds of levels of power in society, including the government. Over time, what that meant is that we were humanised as, and there developed a sense of compassion for what we were struggling with, and a wish to support us.

“And so I think there’s little doubt when I say that, if we had not had Aids, we would not have equal marriage. It’s not a simple equation. There’s an enormous amount of effort from organisations like Stonewall around promoting equality and preventing homophobia, transphobia, etc. It was atan enormous cost but we were having to pay that cost anyway, in terms of Aids. But we benefited from it in this in this way.”

These developments while “heartening” for Rupert are also “fragile”.

“I think that they’re not complete. It’s not embedded in our society, they can change at any time. And you can see that in Eastern European countries, and also Russia, and the way our European governments are shifting more to the right. There’s a much more of a risk that rights can disappear pretty much overnight, just as quickly as we gained them.”

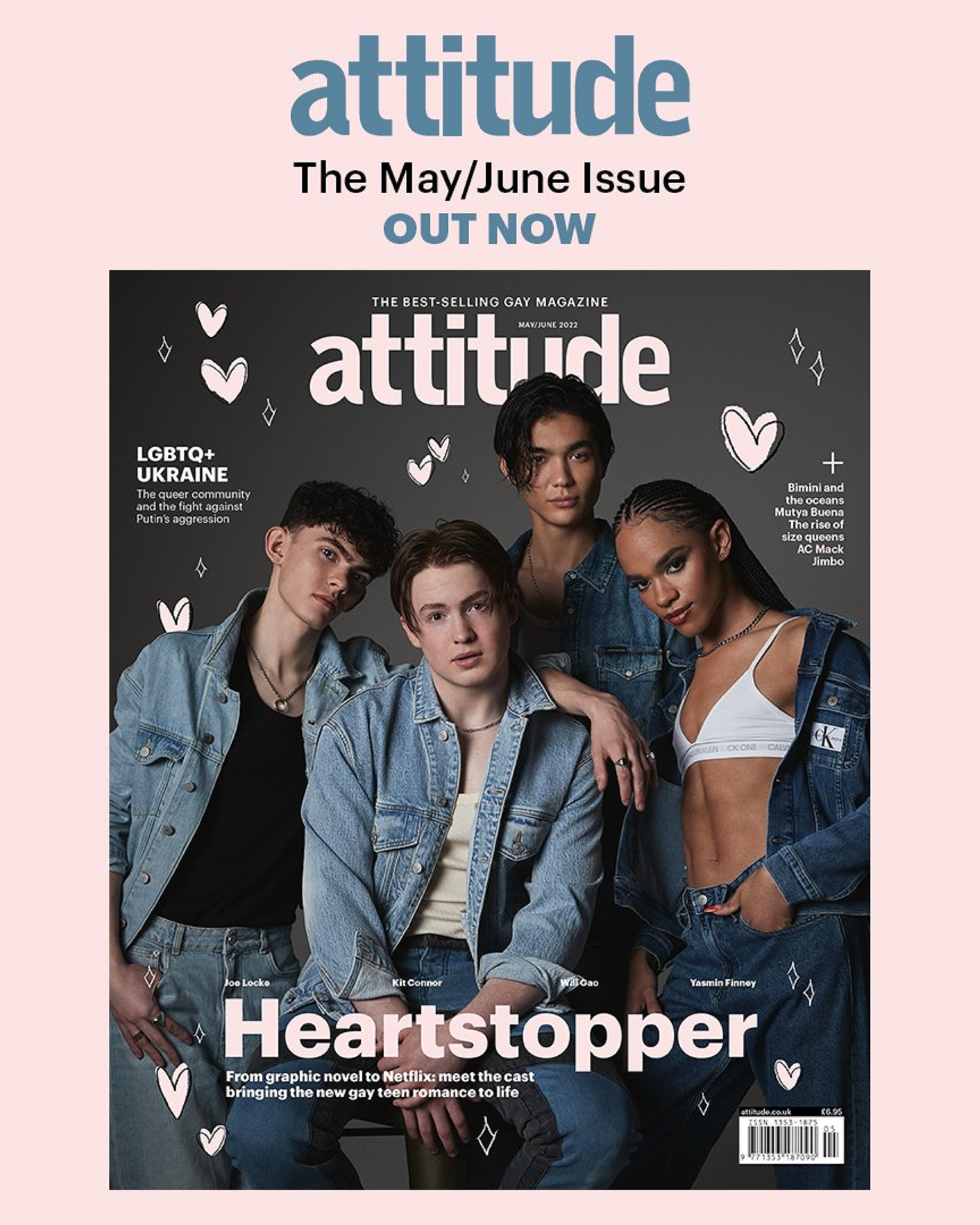

The Attitude May/June issue is out now.