The Lavender Scare: A history of the anti-gay witch-hunt

It's estimated around 10,000 people lost their jobs in the US for being, or being thought of as, gay.

By Will Stroude

Words: Hugh Kaye; pictures: Wiki Commons

Imagine if you can: you’ve worked for an employer for many years without any problems. No one has ever criticised you and you’re happy in your job.

You handle important information, maybe it’s of a sensitive nature. Then, without warning, you are hauled into your manager’s office and asked all manner of personal questions by your boss or an HR executive. Minutes later, your career – your entire life – is in ruins.

Sounds crazy, right? Or maybe it’s in a country with a totalitarian regime. But no, this is exactly what happened to thousands of government employees and members of the armed forces in the United States in the years following the Second World War – and was still going on, to an extent, until the 1970s.

This was the Lavender Scare, that ran alongside the “reds under the beds” panic which began in earnest in the fifties. The phrase seems to have been inspired by Republican senator Everett Dirksen’s use of the term “lavender boys” to describe homosexuals at the time.

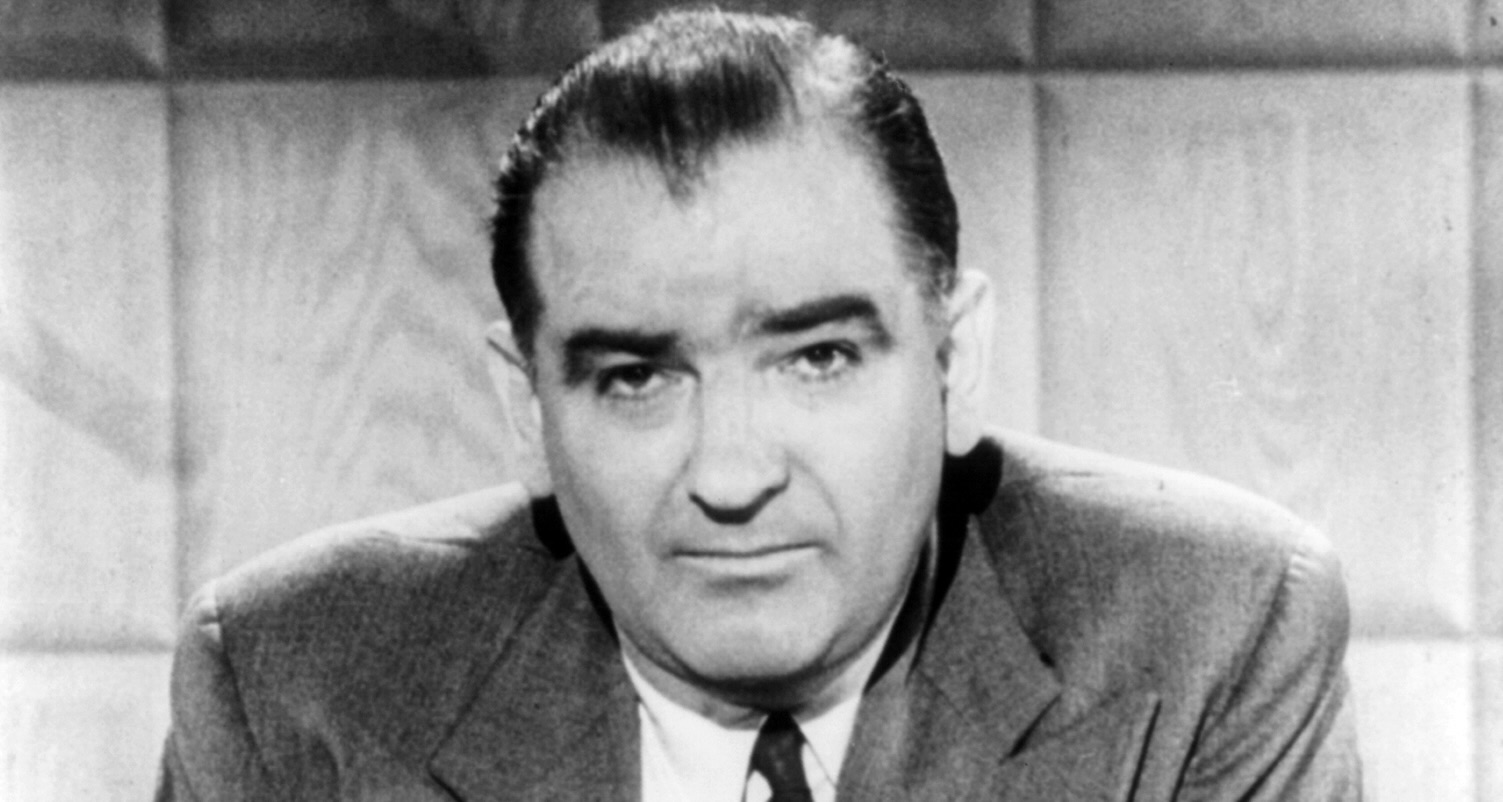

The driving force behind both witch-hunts was the US senator Joe McCarthy and his right-hand man, attack-dog lawyer Roy Cohn. One of the sadly ironic parts of the story is that it’s now believed that McCarthy may have been gay himself – there is no doubt, despite some ludicrous explanations, that Cohn certainly was.

Joseph McCarthy (Photo: Wiki Commons)

One of the worst periods of political repression in American history started in 1940 when President Franklin D Roosevelt and some of his advisers were persuaded by psychiatrists of the need to begin screening programmes to determine the mental health of potential soldiers – the US had not yet entered WWII – to cut back on the possible cost of mental rehabilitation of returning veterans.

Although there was no mention of homosexuality in the earlier stages, references to gay servicemen (and it was mostly men in those days) were added within 12 months.

Following the defeat of the Nazis and the occupation of large parts of eastern Europe by the Soviet Union, the fear of communism grew and swelled in the United States. But while the infamous question: “are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” was heard often in the halls of Congress, security personnel were also saying, at least as often, something along the lines of: “It has come to our attention that you are a homosexual. Do you want to comment?”

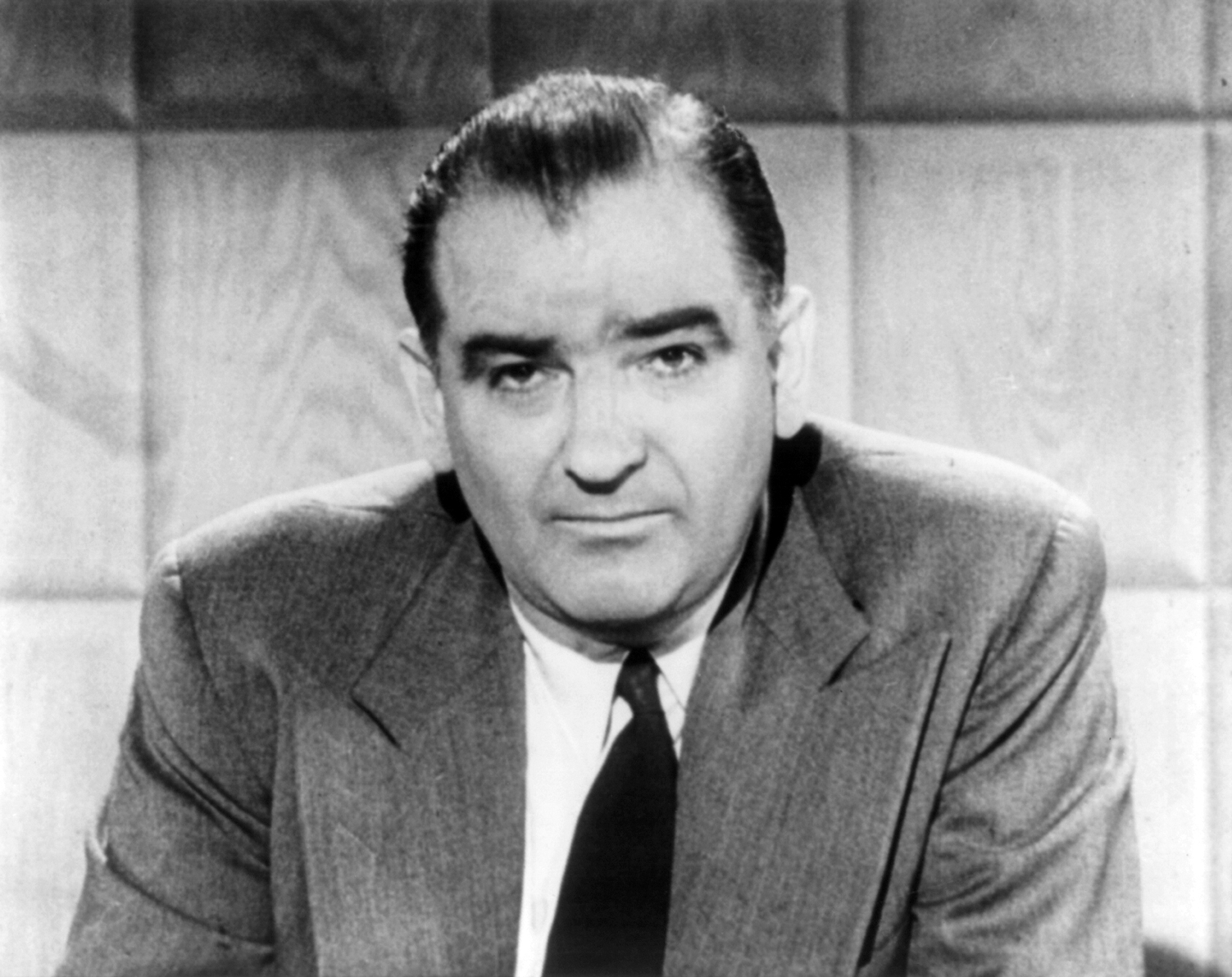

Roy Cohn (Photo: Wiki Commons)

As former senator Alan K Simpson has written: “The so-called Red Scare has been the focus of most historians of that time. A lesser-known element …and one that harmed far more people was the witch-hunt McCarthy conducted against homosexuals.”

McCarthy began his attacks in 1950, claiming that the US State Department had been infiltrated by communists and, with no real evidence, gay men. The latter, he said, posed as equally serious a threat to national security as Soviet spies.

This fear that gay men and lesbians could be blackmailed into revealing top secret information resulted in a systematic campaign to identify and sack any employee even suspected of homosexuality.

At first, the State Department denied it employed any suspected communists but under intense questioning admitted they had fired 91 homosexuals as “security risks”.

The revelation that there were homosexuals in the civil service caused a public uproar.

US Congress (Photo: Wiki Commons)

McCarthy’s popularity increased dramatically and the media and members of Congress began calling for an investigation.

On 19 April 1950, Republican National chairman Guy Gabrielson reiterated this fear, saying: “Sexual perverts who have infiltrated our government in recent year [are] perhaps as dangerous as the actual communists.”

Two months later, a senate investigation began to look into “the employment of homosexuals and other sex perverts”.

Senate Resolution No. 280 was passed in June 1950, directing “a thorough study and investigation of the alleged employment [by] the government of homosexuals and other moral perverts”.

The Committee of Expenditures responded by creating what became known as the Hoey Committee whose task was to consider why employing gay men and lesbians was “undesirable”.

Officials from the Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and sections of the armed forces were interviewed.

The committee’s findings were not released until December of that year and although not one case of a homosexual betraying secrets as a result of blackmail was found, Hoey concluded that gay men and lesbians exhibited weak moral character, had a “corrosive influence” on other employees and that “one homosexual can pollute a government office”.

According to author and historian David K Johnson, during this time, federal job losses due to accusations of homosexuality rose from about five per month to 60.

In his book, The Lavender Scare, he wrote: “At the beginning of the Cold War and the heightened concern about internal security, the State Department began campaigns to rid the department of communists and homosexuals, and they established a set of ‘security principles’ that went on to inspire the creation of a dual loyalty-security test which became the model for other government agencies as well as the basis for a government-wide programme under President Eisenhower’s administration.”

The Hoey report was sent to US embassies and foreign intelligence agencies around the globe, Johnson wrote, becoming part of federal security manuals. Supposition, in effect, became fact. Between 1947 and 1950, more than 1,700 applicants for federal jobs were denied positions due to allegations of homosexuality, according to Marc Stein in his book Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement.

Together, McCarthy and Cohn, who many years later were disbarred for unprofessional and unethical conduct, were responsible for firing dozens of LGBT people and often frightened off opponents by using rumours of homosexuality. McCarthy is said to have often told reporters: “If you want to be against McCarthy, you’ve got to be either a communist or a cocksucker.”

McCarthy and Cohn (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Maybe not surprisingly, one of his allies was J Edgar Hoover, the all-powerful head of the FBI. Rumours have always abounded about Hoover’s sexuality but David Johnson, who is gay himself and specialises in LGBT and gender history, dismisses the idea, saying the speculation relies on “the kind of tactics Hoover and the security programme he oversaw perfected: guilt by association, rumour, and unverified gossip”.

What is not in doubt is that in 1953, in the closing months of Harry S Truman’s presidency, the State Department reported that it had fired 425 employees following allegations – yes, just allegations — of homosexuality.

According to Johnson, things got so bad in the State Department, that male employees, petrified of being branded gay, refused to be seen in pairs and when introducing themselves, included riders such as: “I’m married with three children.”

In 1953, President Eisenhower, Truman’s successor and the man many Americans credited with winning the war, signed Executive Order 10450 which prohibited homosexuals from working for the federal government.

“Sexual perversion” was added to a list of behaviours that would keep a person from being employed and new procedures to search out homosexuals were frequently used in interviews and to look for signs of sexual orientation.

Investigations also looked at places individuals frequently visited, such as gay bars, and people were even seen as guilty by association. Policemen were encouraged to clamp down on gay meeting places and share arrest records. Civil servants were offered lie-detector tests as the only way of establishing their “innocence”. Once again, thousands of people lost their jobs or resigned – some were even driven to take their own lives.

The executive order, says Allan Bérubé in Coming Out Under Fire, led to hundreds of LGBT people being outed. Approximately 5,000 are believed to have been fired. The number includes private contractors and military personnel.

By the mid-fifties, Berube writes, the repressive policies had been extended to state and local governments, covering at least 12 million people – more than 20 percent of the US workforce – who had to sign oaths attesting to their “moral purity”.

In 1973, a federal judge ruled that a person’s sexual orientation could not be the sole reason for termination from federal employment but as Suyin Hayes reported in Time magazine, as recently as 1980 a linguist at the National Security Agency (NSA) was suspended and told he was going to be fired for “living a gay lifestyle”.

Executive Order 10450 was not fully rescinded until 1995 and continued to bar gay people from entering the military until it was replaced by “don’t ask, don’t tell”. The order was finally totally rescinded by President Barak Obama in 2017. In January that year, following a suggestion by Senator Ben Cardin, the State Department formally apologised. Cardin noted that investigations into the homosexuality of federal employees continued into the 1990s.

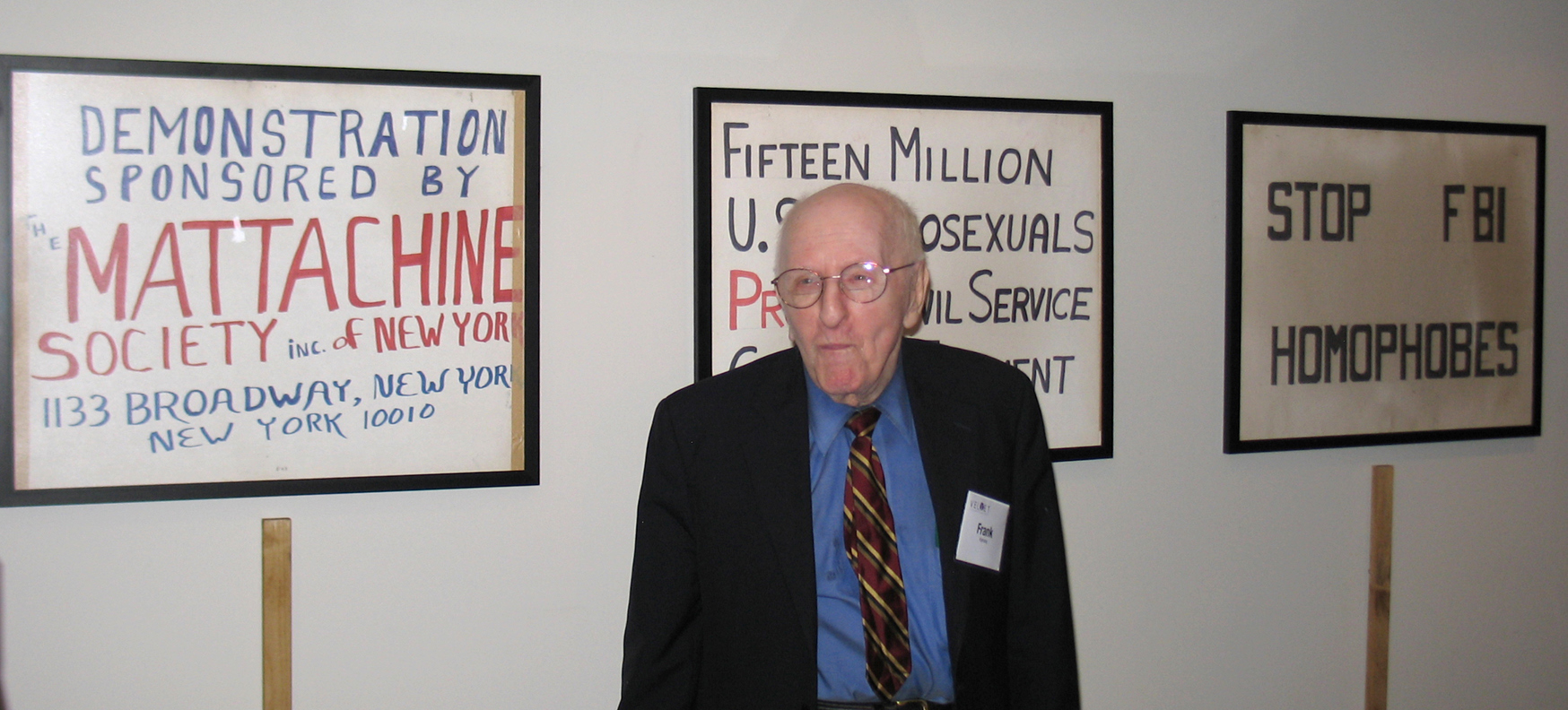

Frank Kameny at Washington DC Pride, 2010 (Photo: Wiki Commons)

One of the few positive things to come out of the Lavender Scare was a new breed of gay activists.

Among these was Frank Kameny. Dismissed from his job as an astronomer by the army’s map service in 1957, having been arrested in San Francisco, then barred from working for the federal government in the future, he took his case all the way to the Supreme Court.

Kameny was forced to write his own brief and claimed that he was being treated as a second-class citizen. He went on to say anti-gay discrimination was “no less illegal and no less odious” than being discriminated against on religious or racial grounds. His case, he maintained, was not one of national security but of human rights.

He lost, and never held a paid job again. However, supported by friends, and using his own name – unusual for the time – he led pickets in front of the White House, the United Nations building, and the Pentagon. He also helped other federal employees who had lost their jobs.

He testified before Congress, drafted a bill in a bid to overturn Washington DC’s sodomy laws (it became law in 1993), and, in 1971, became the first openly gay candidate for Congress. He lost that battle too but ensured that the topic of gay rights was discussed at the White House for the first time when he met with presidential aide Midge Constanza in 1977. He was also present, just 11 months before his death, when President Obama officially repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 2010.

Frank Kameny standing in front of signs once used during protests, 2009 (Photo: Wiki Commons)

By 1969, several federal courts had ruled that the policies inherent in the lavender scare were unconstitutional but in places such as the FBI and the NSA, the ban on LGBT people lingered on until the 1990s when President Clinton finally consigned them to the rubbish bin of history – where they belonged.

In his book, David Johnson outlined how the crusade against homosexuals easily outlasted the “red scare” and claimed that the words “security risk” became a code for homosexuality. Up to 10,000 people lost their jobs, he estimated.

And there were offshoots of the Lavender Scare. The Florida Legislative Committee (FLIC) was founded in 1956 with the sole purpose of investigating and firing gay public school (not private, as in the UK) teachers, aided by the Johns Committee, which claimed homosexuals were carriers of degenerative disease who were a greater menace than child molesters.

Fortunately, FLIC was its own undoing. In 1964, it published the Purple Pamphlet, priced at 25 cents per copy. The idea was for readers to see gay men as sex fiends but it included explicit photos of gay sex, which led to an enormous public backlash. FLIC disbanded in 1965.

Time was running out for the likes of McCarthy and Cohn. Viewers watching some of the senate hearings saw McCarthy as reckless, dishonest, and a bully. According to Richard M Fried’s Nightmare in Red, his popularity fell from 50 percent positive to just 34 percent between January and June 1954, and 45 percent of people had a negative opinion of him in June, compared with 29 percent at the beginning of the year.

Fellow Republicans began to see him as a liability. He also came under fire from the hugely popular television journalist Edward R Murrow, who said that McCarthy had consistently stepped over the line between investigating and persecuting.

Finally, McCarthy was censured and condemned by the Senate, and politicians and the public alike began to ignore his speeches. He died in May 1957 and his seat was won by a Democrat.

Cohn, who has been played on stage and screen by the likes of Al Pacino, James Woods, and Joe Pantoliano, was disbarred in 1986 after becoming involved in numerous scandals including misappropriation of clients’ funds, lying on a legal application form, and pressuring a client to change his will in an effort to make himself a beneficiary.

The man who, according to his biographer Sidney Zion, once described gay teachers as a “grave threat to our children”, died broke in 1986 at the age of 59, following complications from HIV/Aids. Even the supposedly diamond cufflinks given to him by future president Donald Trump turned out to be knock-offs, according to Time magazine.

But his spectre and that of the Lavender Scare lived on for many years. Former State Department official John Hanes, who enforced the witch-hunting policies, seemed to have few regrets when he appeared in a 2017 documentary made by Josh Howard, although he admitted he wouldn’t do the same again today.

Howard told The Guardian in 2019: “Every government person we spoke to said they believed they did what needed to be done. We were surprised as we started reaching out to them for interview, because we expected them to say ‘no’.

“But we began to see why that was: they didn’t feel remorse, or embarrassment or contrition. One of them said: ‘I am a patriot and I was carrying out the orders of the president’.”

But maybe we should rest on an epitaph stitched into the Aids memorial quilt. It reads: Roy Cohn. Bully, coward, victim.