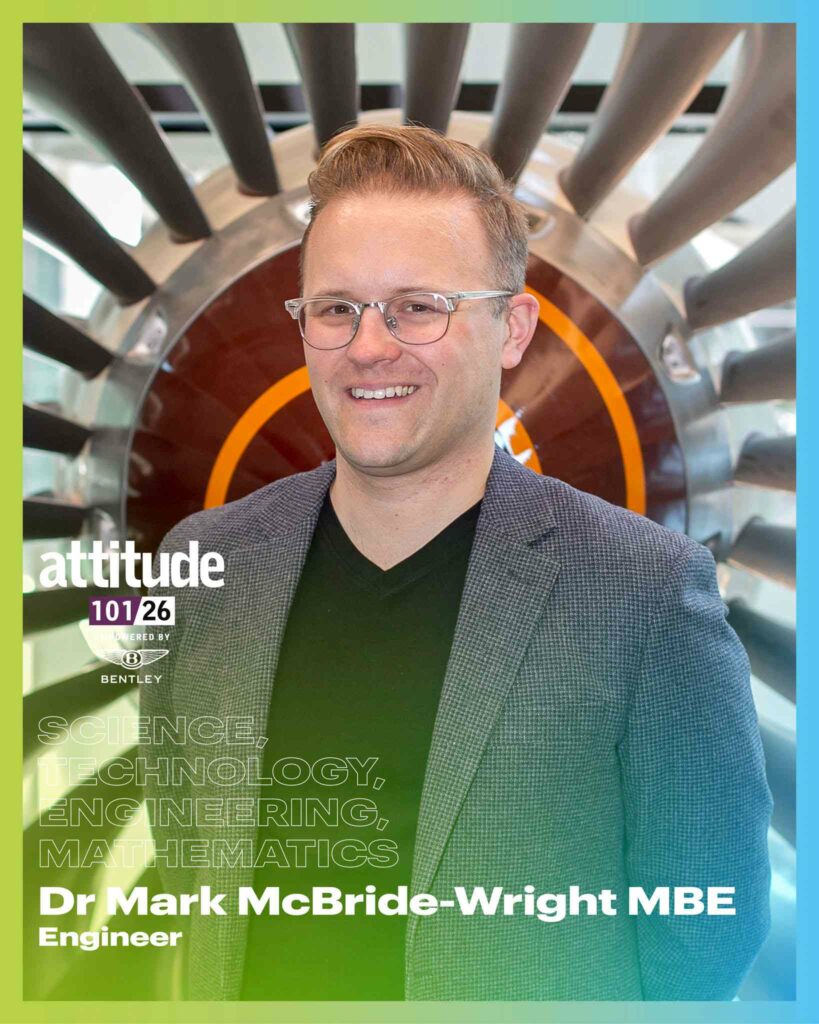

‘Having to monitor and self-censor… that eats away at who you are’: How Mark McBride-Wright is changing engineering culture for all (EXCLUSIVE)

Dr Mark McBride-Wright MBE, leader of the 'STEM' category of Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley, wishes "for the LGBTQ+ community to be thought of as a community of talent"

By Dale Fox

A few years into his career as a chemical engineer, Mark McBride-Wright realised something was wrong, even if he couldn’t yet name it. “Having to monitor and self-censor,” as he describes to it to us over Zoom, a wall of accolades sitting behind him.

McBride-Wright, the leader of the STEM category of Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley, has spent the past decade challenging the culture that made that kind of self-erasure feel normal.

Through Equal Engineers, the consultancy he founded after years working as an engineer, he has become one of the most influential voices arguing that engineering’s macho norms are not just exclusionary but actively harmful — to queer people, to women, and even to the “cis, white … heterosexual” men the culture was supposedly built for.

In 2009, aged 21, McBride-Wright had just become engaged to the man who would later become his husband when he was offered a funded PhD place at Imperial College London. The opportunity was prestigious, but it came with a complication: the programme was sponsored by a state-owned Qatari petroleum organisation, raising questions he says he never expected to have to ask himself.

“Would it mean I’d have to go back in the closet?”

“I was worried,” he says. “I had a digital footprint. I was worried that I was going to have to spend time in the Middle East. Would it mean I’d have to go back in the closet?”

He considered turning the offer down and choosing a safer path that would require less explanation. Eventually, after speaking to Imperial College, he was reassured that his contract would sit with them and he accepted.

“That’s one area where my life could have gone on a different journey based on my identity,” he explains.

The realisation that identity could quietly shape opportunity stayed with him. Years later, while working full-time as an engineer, he found himself with spare evenings and a growing sense of frustration. “I was bored,” he says. “I was like, ‘What am I going to do?’”

He began volunteering with the Institution of Chemical Engineers, joining a local London members’ group. In 2013, that group ran its first diversity survey, finding that only around 15 respondents identified as LGBTQ+.

Around the same time, he attended an event organised by the Women’s Engineering Society on gender diversity. It was the first time the language of representation and role models entered his professional vocabulary. “My whole eight years at university, I hadn’t even once attended anything on underrepresented groups or lack of inclusion,” he says. “It just wasn’t spoken about.”

Moment of transcendence

A turning point came in 2014, at a Royal Academy of Engineering event held in partnership with Stonewall. It was the first space in which McBride-Wright saw his professional and personal lives brought together so openly. What followed was what McBride-Wright describes as “a moment of transcendence”.

“I thought this just cannot be another event that leads to some bullet points getting put on a website that no one reads,” he says. “I really felt I need to do something from this.”

Soon after, he connected with others from the same event who were thinking along similar lines. That December, InterEngineering was born, a volunteer-led peer support network for LGBTQ+ engineers and allies.

InterEngineering offered visibility, community and a place to speak openly in a profession where many people still felt isolated. “We were the organisation that essentially became an incubator for LGBTQ+ talent who wanted to create an in-house network at their employer,” he says, adding that some members went on to establish internal Pride networks within major firms, including Airbus.

Creating Equal Engineers

As the network grew, so did McBride-Wright’s profile. He was featured in the Financial Times Future Leaders list, received industry awards, and saw his employer promote his achievements internally. The success was energising, but it also exposed a tension.

“I constantly had this grapple of what I’m doing outside of work and what I’m doing in work,” he says.

Eventually, he reached a decision. InterEngineering, run entirely by volunteers, was no longer sustainable. At the same time, McBride-Wright and his husband were planning to start a family. So, he stepped away from engineering roles and founded Equal Engineers, bringing InterEngineering under its umbrella and formalising the work into an organisation designed to operate at scale.

Where InterEngineering focused on peer connection and visibility, Equal Engineers was built to work across engineering, construction and manufacturing. It combines research, leadership training, student development and consultancy, expanding the original model to support other underrepresented groups, including women, ethnic minorities, disabled and neurodivergent engineers, while helping employers build and retain inclusive teams.

As Equal Engineers began working with larger organisations, McBride-Wright sensed a limit to how far existing diversity arguments were reaching. “I could feel that something wasn’t quite landing,” he says. “People were sort of, ‘Yeah, yeah, it’s important, but we’ve got other things to focus on.’”

“We have this lack of psychological safety”

A breakthrough came when he looked to his original discipline. Trained as a safety engineer, McBride-Wright began examining suicide data across engineering, manufacturing and construction.

“The Office for National Statistics data showed that you are more likely to die by suicide than, say, a typical hazard,” he says.

Equal Engineers’ own research reinforced the picture. In its first masculinity in engineering study, nearly one in five respondents reported losing a work colleague to suicide, and one in five also reported suicidal ideation or self-harm. In the 2021 dataset, that figure rose to one in four.

“These risks get designed out, they get minimised, they get tracked,” he says. “And yet here we are. We have this lack of psychological safety potentially being the thing that’s driving this high incident rate.”

The significance of that work has increasingly been recognised within the profession itself. In 2023, McBride-Wright was awarded an MBE for services to diversity, equity and inclusion in engineering, acknowledging the impact of his efforts to connect workplace culture, leadership and safety.

But for McBride-Wright, the honour only reinforced a conclusion he had already reached. Engineering’s macho culture, which prizes emotional restraint, was shaping behaviour in ways that made people unsafe.

“We want people to be physically present and mentally present”

“Having to monitor and self-censor and profile the pronouns of your partner and all that if you’re not out,” he says, “that eats away at who you are inside.”

For him, the consequences extend beyond individual wellbeing — they affect how people operate in environments where attention and judgement are critical. “In high-hazard industries, we want people to be physically present and mentally present, not physically present but mentally absent because … their mind is somewhere else.”

He adds: “In the last few years, we’ve had an evolution of masculinity and positive masculinity and manhood and more positive male role models coming forward and showing a different side of masculinity, that we don’t have to just be angry all the time as our default reaction.”

This understanding now shapes how he thinks about leadership and the future of the profession. “We need engineers to just be focused on doing the engineering and not be preoccupied by other stuff,” he says. “Engineers create the solutions to a lot of the problems we have today.”

Challenging stereotypes

That focus also begins earlier than most organisations acknowledge. “If we’re not also changing the hearts and minds of people on the conveyor belt of engineering education, then we’re missing a trick,” he says.

For queer engineers entering the profession, his wish is simple. “I want them to be walking into a business where they don’t have to self-censor or hide. They can celebrate milestone achievements in their life, whether that’s getting engaged, starting a family, or even small things like whatever they’ve done at the weekend with their wife or their husband or their fiancé.”

Stereotypes in engineering persist because they’ve rarely been challenged from within. But McBride-Wright’s work is changing that. As he says, “I’d like to see [inclusion] extend beyond just rainbow cupcakes and Pride Month in June, and actually for the LGBTQ+ community to be thought of as a community of talent.”

Interview by Reece Andrew Ayers.

Get more from Attitude

The full feature and Attitude 101 list appears in issue 369 of Attitude magazine, available to buy now in print, on the Attitude app, or through Apple News+. See here for the full Attitude 101 2026 list of honourees.