This is what it’s like to be an LGBTQ activist in Russia right now

Dan Glass visits Russia to discover how the government's anti-LGBTQ policies are affecting the queer community.

By Will Stroude

This article was first published in Attitude issue 317, January 2020

I remember hearing, at the beginning of 2018, about the LGBTQ internment camps in Chechnya and shivered at night wondering what to do. About a year later, a few weeks before Holocaust Memorial Day, I spoke to my grandmother in my dreams and her words “Never again, ever” leapt into my mind the next day.

She survived the Nazis during WWII by “hiding in plain sight”. A lesson worth bearing in mind in Russia today.

Hundreds of people came together to organise a Queer Power flash-mob outside the Russian Embassy in London, to protest against the purges in Chechyna.

Fast-forward 10 months and I am visiting Russia with a delegation of LGBTQ and HIV-positive activists to mark the 16th anniversary of the repealing of Section 28, the Conservative law that banned the promotion of homosexuality in Britain, and to build international understanding and solidarity for those across the world still being affected by its legacy.

Two weeks into my visit, I find myself getting emotional and I’m knackered. After talking about the same issues in meeting after meeting and taking photos of new connections, I’ve become numb.

I meet many courageous people, the first of whom is Igor Iasine, who not only created part of LGBTQ freedom parades and interventions here in Russia — a country that bans Pride marches and any form of sexual education outside of the nuclear family — but also trail-blazed a movement when the news of the LGBTQ murders in Chechnya began.

In a country where most protests are banned, Igor and the other activists held “teach ins” to inform and equip people with a tool-kit to challenge the government’s law.

One night they showed the film Pride. The Moscow venue was packed, and Igor was out on the streets sharing leaflets. Word began to spread to unions, public institutions and LGBTQ movements, and lifelines were created for those imprisoned and tortured on the front line. News of the massacres began to disseminate around the world.

Viola

However, the crisis is deepening. The sexual repression and homophobia has led, on average, to approximately one in every 10 gay men, and one per cent of Russians in general, living with HIV — and dying. According to the UN, Russia has one of the fastest growing HIV/ Aids epidemics in the world.

But the campaign for sex education, halting the extra-judicial violence and holding to account those responsible is growing. Igor hopes to screen United in Anger, a film about the courageous and creative tactics used by the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power and the wider health-care justice movement to confront the Aids genocide and fight for antiretroviral drugs.

“A few years ago, a homophobic campaign began, and the state openly involved itself in the oppression of LGBTQ people,” Igor says.

“One the one hand, it has complicated the lives of queer people, but on the other it has allowed us to undertake discussion of the problems and rights of LGBTQ people on an unprecedented level.”

Maria

In the days that follow, I meet Barya, who works night and day in Moscow’s underground and over-filled LGBT+ Centre where people flee homophobia — from their families, colleagues and on the streets all over Russia. Aware that reacting to a tyrannical system is never enough, Barya knew it was time to fight back.

Given that the Gay Propaganda Law bans the promotion of homosexuality in Russia, she founded Barents Pride on the Norwegian side of the border with Russia four years ago, and dreams of a Pride in Russia. Today, Barents Pride needs musicians and artists from all over the world to join them.

I also meet Zoya, another long-time worker at the centre, who in her spare time helps coordinate Russia’s HIV-Positive Network.

If they can, LGBTQ and HIV-positive people flee, with many going to Uzbekistan.

Sasha

However, being LGBTQ there is a criminal offence, so people find themselves immediately imprisoned and at risk of death without healthcare.

Chelyabinsk, in central Russia, is where a meteor fell in 2013, knocking people off their feet and shattering windows in 3,600 buildings. At its most intense, the streaking fireball glowed 30 times brighter than the sun. Today, Zoya is trying to shine a different sort of bright light by launching Russia’s first PrEP trial here. In a country where not only is being gay shameful, but being “ill” also brings shame, she is defiantly creating a system where having sex is not a crime and asking for healthcare is supported. It’s hoped that the result will be equally as earth-shattering.

“You must meet ‘Action’,” the residents at Moscow’s LGBT+ Centre tell me.

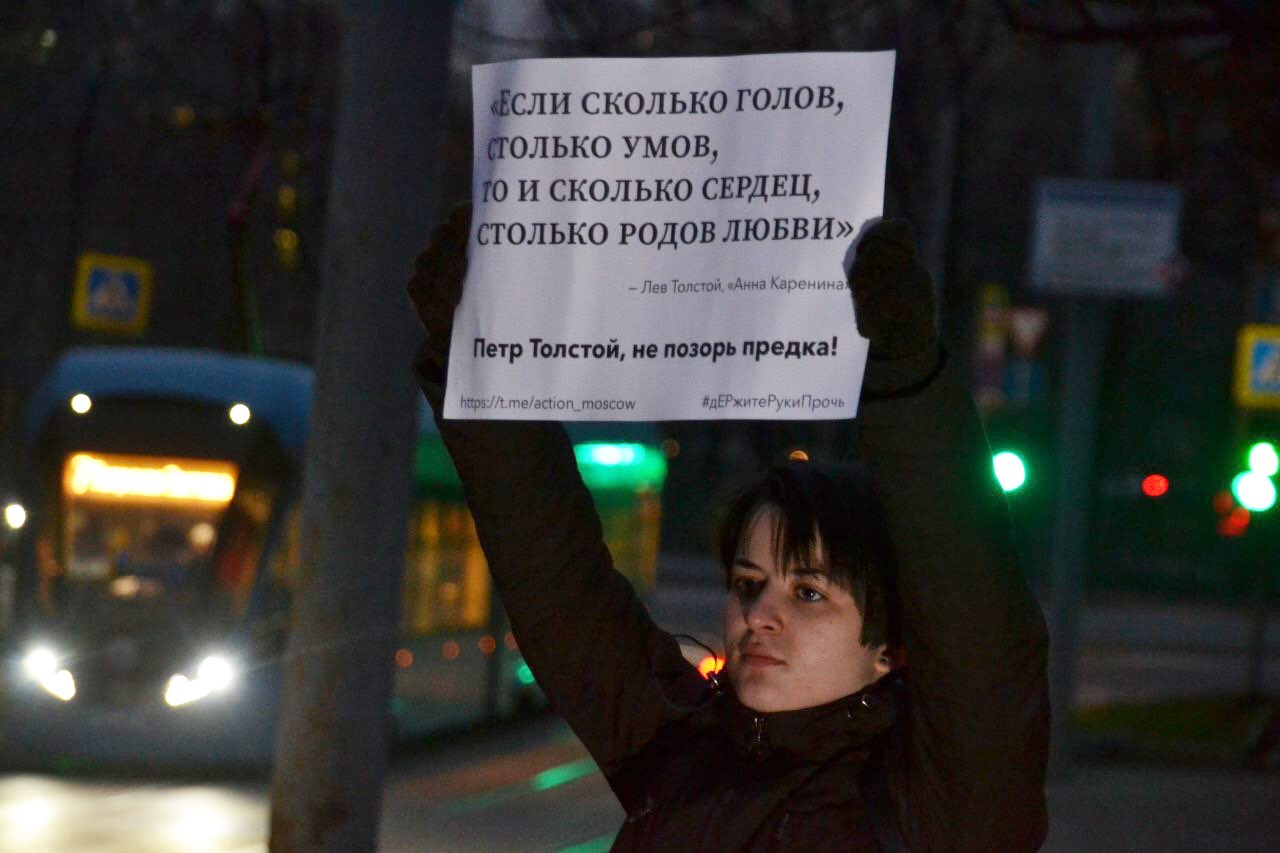

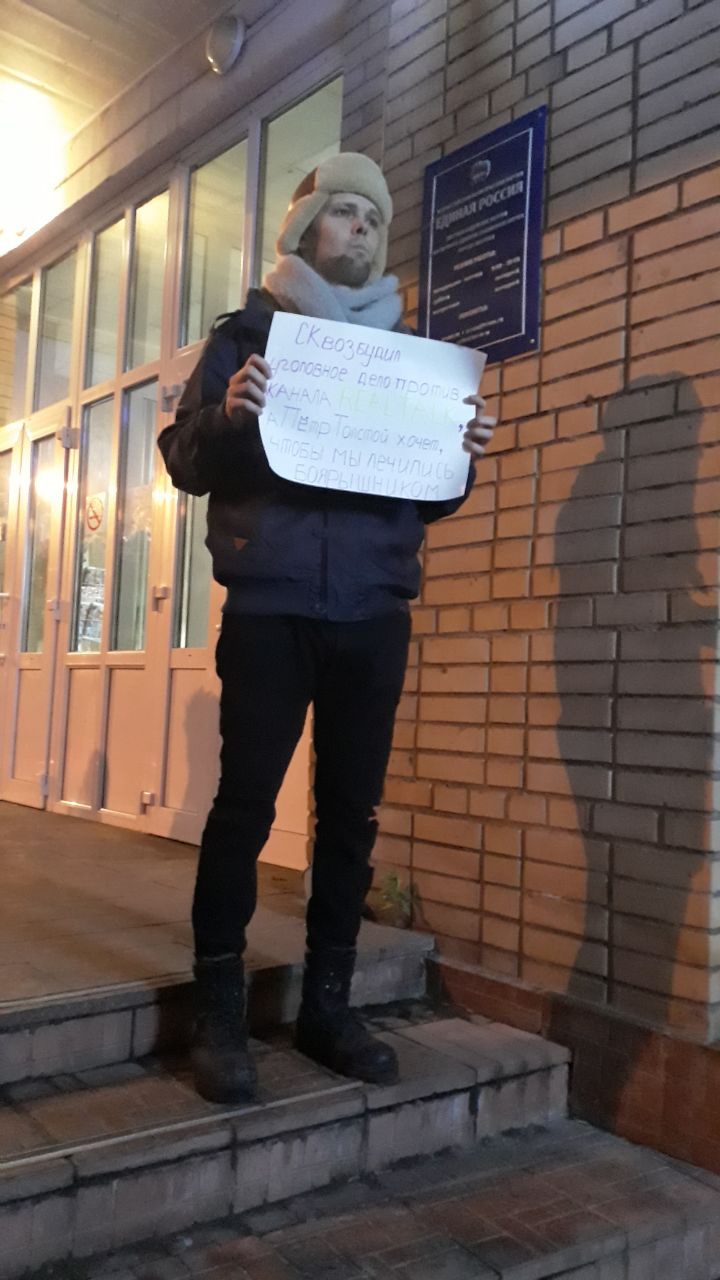

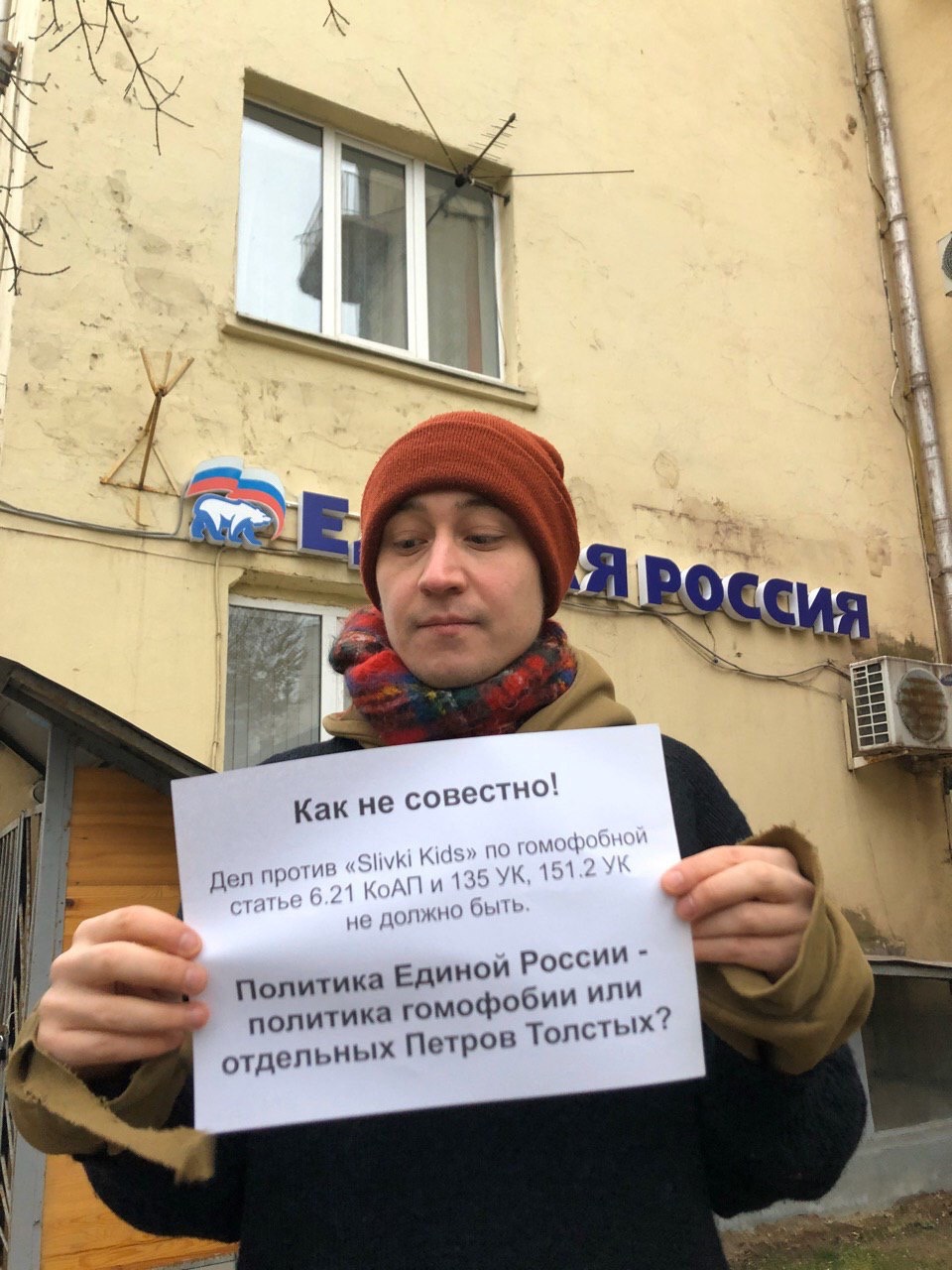

Eve, Viola and Nastya are part of the new movement, Action, the young creative resistance aiming to support an exhausted and traumatised older LGBTQ movement. Since the Gay Propaganda Law was introduced, street interventions and political protests have all but died out.

Eve

Kicked out of their family homes and bullied in school (the video of Nastya’s classmates burning her Pride flag in the school playground went viral), they have nothing to lose and everything to gain.

On 11 October, International Coming Out Day 2019, they protested against Chechen concentration camps in front of the Chechen government office, hoping to bring to life their vision of a Russia free from legislated homophobia, and bring about the creation of LGBTQ protection laws.

They have huge, growing fines and court fees to pay, after being arrested. That night, at goodbye drinks, Eve paints eye-liner on her best mate while wearing a badge saying “HELL — admit one”.

Viola turns and looks at me. A progressive queer Jew in an orthodox conservative country, she is active in the new socialist lesbian movement.

Viola

Hugging me, she whispers in my ear: “It is all about hope. We love our family and friends here in Russia, we don’t want to go abroad.

“We have to show that we have the power inside, and not just the power but brought to life through smart actions. There are some parts of the world where you can’t be yourself, you have to fight. Together we must build this road map.”

That night, looking to let off steam in a queer club after so many intense conversations, I head to Popoff Kitchen where I find the event’s founder, Nikita EgorovKirillov. Soon after the Gay Propaganda Law was introduced, Nikita had his face smashed in and his arm broken by homophobes.

He could have fled the country but refused. Soon after, he found himself on the LGBT+ Blacklist, a bucket-list of those people fascists intend to attack.

Misha

But Nikita refuses to run. Instead, he’s drawn a line in the sand and decides to navigate the system and build a queer revolution from the inside. When safe spaces for queers to congregate were abandoned, he knew what he had to do.

Nikita started a party and a handful of friends came along. More people turned up and even more for the following event. He stayed silent when the media discovered the event, seeking instead to create a safe sacred space in which HIV testing was on offer, posters on sex-positivity and self-care were displayed, play rooms were set up, and nudity, performance, laughter and queer love filled the space. It wasn’t long before a couple (consensually) made love on the dancefloor. Nikita knew things were changing.

Popoff Kitchen now has thousands of people attending each month and queer parties, raves and a renewed sexual awakening are multiplying across Russia.

“But what about the propaganda law?” I ask. “How can people outside Russia help?”

Jim

Nikita shifts to put his arm around me and says: “Don’t leave us isolated. We need you to see what’s really going on here, queers across the world must stick together.”

On my last day, I meet Boris Konakov, the first publicly out LGBTQ HIVpositive artist in Russia. One of the many amazing actions he has been part of seized press attention and captured the public imagination when he and a friend, who is HIV negative, drank each other’s blood, mixed with vodka, to show that sex is a fact of life, to remember the dead, and in response to the government’s Aids-phobic rhetoric. It gives a totally new meaning to Bloody Mary.

During the fall of the Soviet Union, the government of the day publicly stated that if everyone living with HIV died, the problem would die out, too. Thirty years on, the epidemic still rages.

In a nation where 80 per cent of doctors refuse to work with people with HIV and where there are only 10 Aids support clinics throughout the entire country, there are currently one million people registered with HIV. Registered is the key word — the true number could be far, far higher.

Boris Konakov

When Boris heard about the Chechen gay concentration camps in which queers were not only being kidnapped by the police but snitched on and killed by their own families, he handcuffed himself to a bridge named after the father of the head of the Chechen republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, and displayed the message “Stop killing your kids. Would you kill your own kids?” I am in awe of this man. But the danger is real.

“What can we do in solidarity?” I ask.

“Spread information, share activist strategies, generate money for operations, create alternative medical buyer’s clubs to address a serious shortage of antiretrovirals caused by a constant price hikes and trade-wars between the government and pharmaceutical corporations,” Boris says.

He continues: “Lobby for more HIV clinics and develop grassroots ways of fundraising as the government considers any NGO a ‘foreign agent’, and if they don’t agree with them, they won’t allow them to raise funds.”

The key strategy on the road to freedom is mass visibility, to put the issues on the political agenda and provide a true assessment to counter government “statistics” that constantly lower the number of people living with HIV or affected by hate crimes and domestic violence.

Oleg

There are no laws about anti-LGBTQ violence. Even deeper than this is confronting the Russian government’s legislative control on the right to protest and freedom of expression.

“We have to stop being submissive — LGBTQ, women’s and HIV groups are always treated as lesser,” says Boris. “People need carnivals, such as Pride which is currently banned, to cope with the fact of death.

“Only through this can we celebrate life before coping with the fact of death. Carnivals reconcile people with death by celebrating life,” he adds.

With people like Boris, we at least have some hope that it won’t be long before Pride becomes a reality in Russia.