Oz, Carnegie, and Fire Island: The myth and meaning of Judy Garland’s gay icon status

Who’s your best Judy? For us, it’s still the Wizard of Oz star who inspired the 20th-century queer slang in question. Ahead of Wicked: For Good, we celebrate the legacy of a community godmother... and find, on balance, she wasn’t perfect! (Spoiler alert: but we love her anyway)

Earlier this summer, at one of Billie Eilish’s O2 Arena gigs, I witnessed tens of thousands of young girls, many of them queer, screaming the ‘Birds of a Feather’ singer’s name in tribal unison – and all I could think of was Judy Garland. Sensing a star’s energy absorbed, regenerated and multiplied ad nauseam, for everyone’s benefit – performer, spectator, society-at-large – reminded me of the gay men in the audience at OG showbiz stalwart Judy Garland’s legendary Carnegie Hall concerts in 1961.

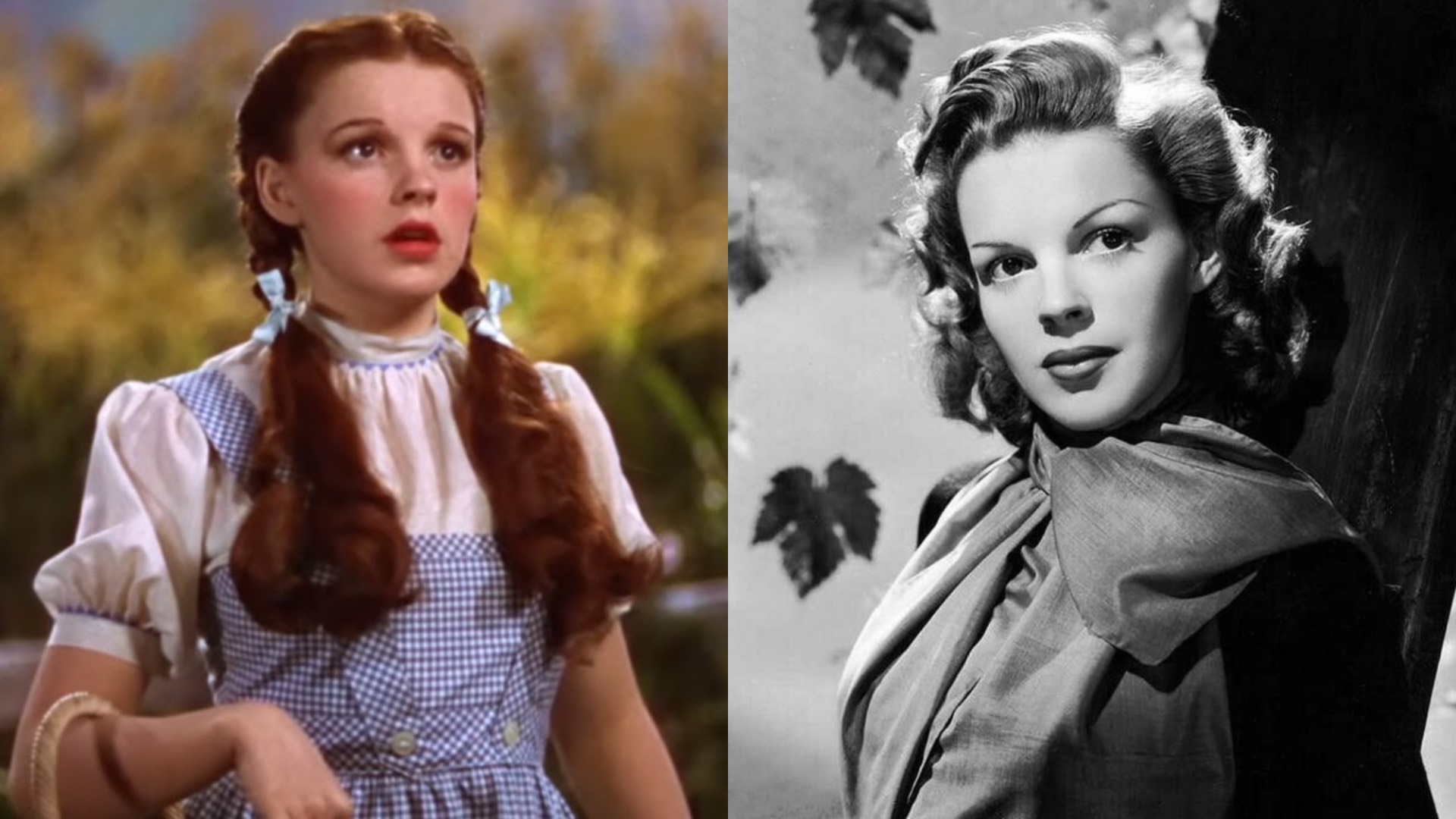

Sure, she shot to fame in The Wizard of Oz in 1939 – her sparkly spirit, a blend of gritty determination and aching vulnerability, resurrected in the perfectly pitched performances of Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande in 2024’s Wicked – but fought through relationship drama and drug addiction to experience arguably her career peak 22 years later with Carnegie. (The first of the two shows was recorded live, released as the double album Judy at Carnegie Hall, and won four Grammys, including Album of the Year.)

In his review for the New York Times, Lewis Funke wrote how “the religious ritual of greeting, watching and listening to Judy Garland took place last night in Carnegie Hall. Indeed, what actually was to have been a concert – and was – also turned into something not too remote from a revival meeting.”

I’ve always imagined this night to have been a distillation of the energy that electrified the gay community when Britney Spears broke through in 1998, or Kylie Minogue reached Fever pitch in 2001; a cultural trend that expanded to encompass the entire LGBTQ+ community with Lady Gaga’s Born This Way in 2011 and a party to which, in 2025, with the rise of Chappell Roan, everyone and their biological and chosen mother is invited.

But there’s one problem with these accounts of the Carnegie shows – I wasn’t actually there to verify them. Indeed, I wasn’t even alive. And of the many gay men who were, many have now surely passed away. (If you were 25 in 1961, you’d be at least 81 now.)

In a 2024 retrospective review of Live at Carnegie Hall, Pitchfork writer Harry Tafoya describes a rare photo of the shows, in which “a line of disembodied hands” reach out to Judy. “They belonged to a group of men whose allegiance to the star was as passionate as it was fraught,” Tafoya writes. “As bound up in their identification with her strength and humour as with the many troubles of her life. Their cohort could only be spoken about in code, and in time, a whole vocabulary emerged to describe them: friends of Dorothy, the boys in the band, Best Judys.”

Tafoya adds authenticity to the picture by citing commentary from the era. “To journalists and outsiders, they were objects of amusement, if not outright scorn: ‘the boys in tight trousers’, ‘ever-present bluebirds’, or as one writer bluntly called them, ‘a flutter of fags’.”

Such acidity makes me question whether my perception of Judy’s importance to gay men is just an inversion of the homophobic commentary that documented and perhaps overstated the relationship at the time. Reviewing a Judy show in New York in 1967, for instance, a Time critic described Judy-ites thus: “A disproportionate part of her nightly claque seems to be homosexual. [They] roll their eyes, tear at their hair and practically levitate from their seats, particularly when Judy sings [‘Over the Rainbow’].”

Digging into history to test the theory, it’s perhaps unsurprising that digitally available public statements from Judy that would make her allyship explicit are hard to come by. Firstly, this was a pre-social media age. Secondly: sodomy was illegal in every US state for the majority of her life. (Illinois was the first to decriminalise it in 1962. It was decriminalised statewide in 2003.) Such institutional, country-wide homophobia might explain why, if Judy was indeed queer herself, as has been speculated, she never publicly came out. (In 2009, biographer Emanual Levy told Advocate: “She slept with women occasionally. However, she never acknowledged that she was bisexual.”)

That said, the quotes that are available are certified doozies. During an interview with CBS in 1967, for example, Judy said: “I think they [gay men] recognise suffering. They’ve been made to suffer so much that they sort of identify with me. And I with them.”

This is an excerpt from a feature appearing in the 2025 Attitude Awards issue. To see the full feature, order your copy of the Attitude Awards 2025 issue now or read it alongside 15 years of back issues on the free Attitude app.