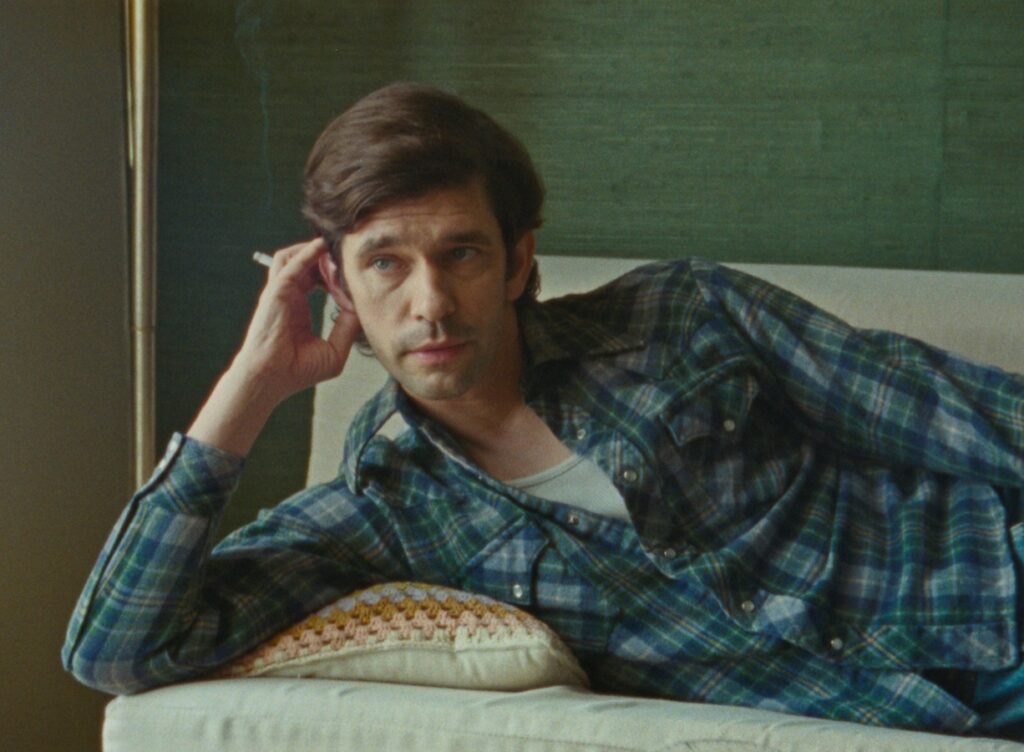

Peter Hujar’s Day: Ben Whishaw, Ira Sachs on LGBTQ history and the art of documenting queerness (EXCLUSIVE)

Attitude catches up with film star Ben about the irrepressible pull of reality TV and "the day that changed my life," as he sits down with his latest director to discuss photography, memory and the process of being interviewed

In his new film Peter Hujar’s Day, actor Ben Whishaw plays legendary photographer Peter Hujar, known for capturing the queer intelligentsia of 1970s New York City, from the late Beat icon Allen Ginsberg to author and public speaker Fran Lebowitz, now 75. (Peter died of AIDS-related complications in 1987 at the age of 53.)

But, as Ben tells Attitude in an interview alongside director Ira Sachs in a London hotel, the artist’s focus extended far beyond human beings – even if the lovers, friends, frenemies and collaborators of his day get a lot of the retrospective attention.

“There’s a book that came out after his death called Night: pictures of New York at night,” the 45-year-old tells us. “I find that particularly beautiful. One picture I love is of broken crockery on a shitty table in some ruined place! I just love that his eye was a spectator to so many different things. Interestingly, he didn’t just photograph gay men, or men, at all, did he? He loved everything. He was open to broken dishes, pregnant women, and a dog. I love that so much about him.”

Ira, 60, says he doesn’t have a favourite photo of Peter’s. “When I love an artist, I love everything about them. I love their failures and successes. I love the good photographs and the bad photographs. I think this is true of his art, but I’ve often thought about it with [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder. There’s only one Fassbinder film, and it’s all of them!”

“I agree,” says Ben. “If I love someone’s work, I love absolutely all of it. I get very annoyed when people are like: ‘But that period wasn’t so good!’ No! I love them! I’m there with them the whole way through the journey with their art.”

In the film, Rebecca Hall plays writer Linda Rosenkrantz, who, on 18 December 1974, asked Peter to write everything down that he did that day. The next day, she invited him over to her apartment to be interviewed about it. Rosenkrantz released the verbatim transcript of the interview in 2021, and the film recreates that exact conversation with a warmth and intimacy that feels staggeringly real.

While Attitude fears the interview you’re reading now may never be made into a film, for what it’s worth, here’s our Q&A with Passages and Love Is Strange director Ira and James Bond and Paddington star Ben, with unfettered meanderings (ours) and epic artistic insights (theirs) left in for good measure.

Attitude: I love that Peter was a queer photographer shooting a lot of queer subjects, and that, if my research is correct, you [Ira] came across this conversation in a queer bookstore in Paris while filming another film with queer sub-texts, Passages…

Ira: Sub-texts? Text!

Yeah, sure, yeah, yeah, yeah. Do you feel, as I do, that there is beauty in this sort of queerness upon queerness? Like a queerness squared? And I say this having just written a retrospective of Brokeback Mountain, which I love, and was written and directed by straight people!

Ira: Right, right, right! Well, yes. For me, I think Hujar’s photographs, when I initially saw them, seemed like a door opening to a queer, artistic world that I wanted to be a part of. And I guess I’m still searching and seeking that community in a lot of the things that I do and make in my life. And I think finding a queer, artistic brother in Ben, who had shared interests, including homosexuality… [Everyone laughs] Fact and fiction! Literally!

I’m interested in homosexuality too!

Ira: Yeah! I think being interested in men in a sexual basis is really a connector to people. Maybe for Peter as well.

Attitude: I know Peter covered a lot of the LGBTQ movement in his work from the ’60s to the ’80s. Is there anything new that you learnt about queer history as a result of researching and making this film?

Ben: I stumble a bit. Someone asked me what I thought about that time. I love his work and obviously one gets a sense through his work of that period. But I feel it’s too big for me to really grasp, in a way. I’m not very good with history. Do you know what I mean, Ira?

Ira: Well, I feel like people talk about the film being set in ’74, and I knew so little [about ‘74] except the details of his communal life, of which I think I know quite a bit now. In the sense this film in its focus on a grain of sand gives me a feeling of being there, in a different time, successfully. Within the world that he lived, the queerness was primary. It was exchanged. It was the topic of creative work, of social life. It was a queer neighborhood, so it was a ghetto, in a positive way. All of that is super generative in a way that I crave.

The picture of his that you own, Ben, is that an original or a print, and do you mind if I ask how you display it?

Ben: It’s not an original, but it is a print by Gary Schneider, the only person allowed to print Peter; a great photographer and a pupil of Peter’s, kind of. He’s a wonderful printer. It’s a more recent print. It’s a photo of Peter, a self-portrait, and he’s sat naked in a chair and it’s very beautiful and quite stark. It has a kind of weight about it. He was very depressed and took this photo of himself. It hangs in my hallway. I really get a lot from sharing my flat with him.

I love any art that captures friendship between gay men and women. Did you know Rebecca Hall before this, and if not, how did you build chemistry?

Ben: We think we met each other a long time ago, 20 years ago, when we were starting out. I can’t precisely remember where that was or what happened! I guess we didn’t see each other for a long, long, long time, until 2024. It was basically like meeting for the first time. Ira did the thing that he likes to do – we didn’t know one and other, and he said, go meet each other in this diner and get to know each other. Just see what happens, actually. So, we did, and we spoke for hours and ate tuna sandwiches!

Ira: The diner has gone! Hector’s [Cafe and Diner]!

I’m all about the minutiae of one’s day, because if you can get pleasure out of making a cup of tea or [organising] your socks, I really feel that’s a key to happiness. I love that this film captures that so well. I know this is a misconception, but I just can’t seem to let it go: I always assume accomplished [people]; actors and directors, must be like Jon M. Chu, the director of Wicked who I saw in a Q&A recently, who said he has to make a thousand decisions a day. I assume people in those worlds are really effective all the time. Do you guys procrastinate though, as we do, as your subject does?!

Ben: I definitely relate to a lot of what Peter talks about. I love to nap! Peter loves to nap. Definitely, the life of an actor, you can have many days where nothing much seems to happen. I very much relate to that. In fact, mostly it’s how life is!

Ira: Occasionally, there are periods in your life as a director where you have constructed some sort of necessity of being productive, which you can’t resist! That asks for you to show up in a very active way. But then, you can go down a hill and there’s a long period of wanting to be there again! I think there’s also a big difference between a director like Jon M. Chu, who makes people money, and a director like me, who does it because I have to… I mean, I’m sure it [Jon’s career] is incredibly challenging in ways I couldn’t possibly imagine, but there’s also an industry that demands his presence because he becomes part of a capitalistic circle that I, for better or worse, am not a part of. I guess in some ways, I was making this movie, we were in one location, equipment in a certain room, cafeteria in another room down the hall, and we were all together and it felt a little like a mini studio. I was jealous of the time there was this apparatus and structure that encouraged constant creativity. The answer is yes and no and yes!

I’ve never asked anyone this before, but the film has gotten me thinking about interviewing in a new way – what is it actually like to be interviewed, in your position?

Ben: It really depends on what is the interview is in aid of. If it can feel like a real exchange – this feels like we’re actually having a conversation – then that’s really nice. But if, essentially, you’re just being asked to give some soundbites that have been preordained and you can’t deviate from them, and you have to just sell something, I find that excruciating. I’m not very good at it. [But] when it feels like there’s some listening going on from both sides…

Recently, I had to interview my friend Ruth Wilson for a magazine, so I got to be on the other side of it. I felt incredibly nervous. I had to really plan what I was going to ask. Then there were moments when I thought: ‘Oh no, maybe the conversation is running dry! I don’t have the next question lined up in my head!’ There’s an art and a skill to it I’d not really considered before from the interviewer’s side. It’s drawing something out.

If you could choose any notable, or not notable, day from your careers to recount for a project such as this, what would it be?

Ira: For me, it would always be today. Particularly when I’m in an interview, I’m trying to be as present as possible. Pay attention to things in the immediate. So, what would interest me would be the things close at hand.

Ben: What sprang to mind, into my memory, was the day that changed my life. It was a day I had a very important audition for a theatre job. I didn’t realise when I went in for this audition, it turned out it was to play Hamlet. [Ben played the lead in Trevor Nunn’s 2004 production of Hamlet at the Old Vic.] I thought it was to play Rosencrantz or something, a smaller role. I remember so vividly this day. Although I hadn’t thought about it until you just asked the question and it just came back. It was snowy, the jacket my boyfriend had given me at the time, a sheepskin coat, smelled musty. I remember so many things!

Ira: When you say that, and include your boyfriend, what role did the closet have on you or for you at that moment?

Ben: That’s a whole other thing. It was really very big, when I look back. It was frightening to feel, particularly once I became someone people had heard of, and seemed to be interested in. I felt like I was guarding almost a dirty secret. It was very horrible. I would never have talked about my boyfriend at that time.

Ira: Did you have two closets? You came out of one then came out of another? You were out in your social world, had boyfriends?

Ben: Yes. But then, my parents didn’t know, and lots of other family. Once they knew, it was another coming out to the world.

In the spirit of the film, did you do any record-keeping of making it, or have you in the past – diaries, photos?

Ira: I have a diary of the making of Keep the Light On. It’s actually still online.

Ben: Wow!

Ira: Occasionally I go back to it, to remember certain things. It’s useful to me. Since then, I have not. I wish I did, because I would like to be in closer contact with my own feelings.

Ben: I took some photos and they’re really lovely and evocative for me. I always like to keep a notebook. I have a diary. It’s got random bits of stuff in it. I haven’t brought it with me today, but usually I do. I look back at what I was thinking or feeling when I was making the project. I actually feel very connected to those projects a year and a half later. Sometimes you don’t, and you need a bit of a prompt. So yes, I do have things. What I would say is, this is one of the happiest… I felt incredibly happy to have been making this film. It was spring. It was something we really cared about. We didn’t know what it was going to be. It’s real-life, which is always challenging. It’s still quite vivid in myself.

I love that the making of this film must have involved a lot of long conversations, because that’s what it’s about. Whereas media is so fast paced – we don’t have five minutes to rub together to talk about anything. Was that what it was like?

Ira: For me it was. Ultimately, my artform is a series of conversations that generate images. There’s always collaboration at the centre. Definitely many more conversations with Alex Ashe, the cinematographer, than with Ben or Rebecca. With the actors, I try to keep unspoken a lot of things, in order to discover together. But with the cinematographer, there has to be a deep, circular conversation around the images we’re making. Hours and hours and hours of conversation.

I was reading an interview with Linda Rosenkrantz in the New York Times earlier. She said she watches Keeping Up with the Kardashians and Project Runway! I was thinking, with all these amazing names I heard in the film – Allen Ginsberg, for example – I want those people to live on in future generations of queer people. But for me, I had to seek them out; no one taught me about them. Sometimes I worry [that a barrier is] people think they can’t be into low culture and high culture, or low culture and alternaculture. But you can. Are there any examples of low or mid-culture that you guys like?

Ira: I think once you develop a curiosity in something, you follow paths. I read an article in the late ‘80s about David Wojnarowicz, which included a mention of his lover and mentor Peter Hujar. Then I see there’s a show at Matthew Marks Gallery of Peter Hujar, so I seek that out. I walk in the door, and I see photographs of Charles Ludlam, Susan Sontag, Fran Lebowitz, Allen Ginsberg. I began to follow certain entryways that this world led me to. Also, I seek out queer and gay writers because I find it so intimate to read versions of stories that seem so familiar to me. You do that over 40, 50, 60 years, you end up with a breadth. A limited breadth.

And then, I only watch one thing on television, which is Housewives! Every night, my husband and I, he gives me 20 minutes of Housewives before I fall asleep.

Ben: Which one though?!

Ira: Beverley Hills. Salt Lake City. Atlanta. Miami. And that’s it. I don’t recommend it! It just happens to be, for me, mainlining something. But I think what Housewives and reality [TV] do is something like Hujar does: it gives you a connection to the minutiae of everyday life, even if it is constructed. It is quite real. The dramas are there, waiting for you to turn them up.

Ben: I don’t watch Housewives. I find it too much. I don’t find it relaxing company in any way. But my partner really loves them all. I like Traitors. I think that show is fantastic! I am devoted to it!

Peter Hujar’s Day is out on 2 January 2026.