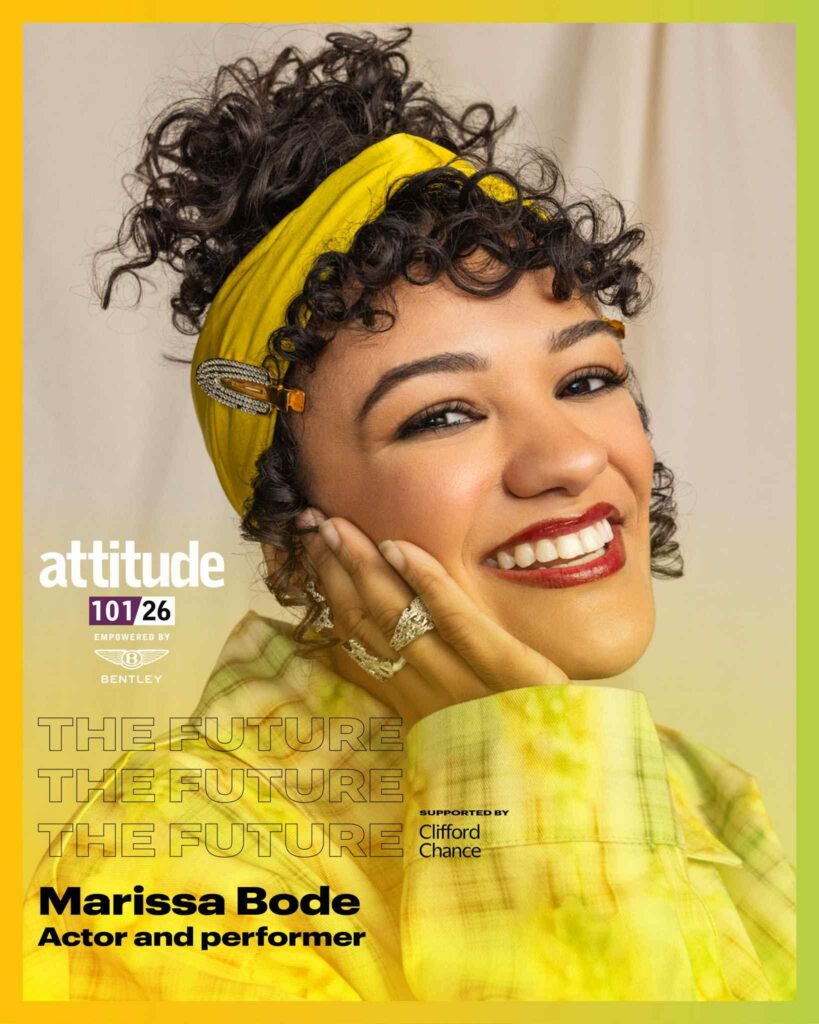

‘Celebrate your queerness as much as you can’: Wicked’s Marissa Bode on being a proud role model in Hollywood (EXCLUSIVE)

The actor and performer leads the 'The Future (Under 25), supported by Clifford Chance' category of Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley

By Dale Fox

Marissa Bode will probably never forget the moment she got the call to appear as Nessarose Thropp in the Wicked film franchise alongside Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo. Just one year out of college, she was working part-time as an after-school kids’ art teacher and living in “a really crappy apartment with a brown stain on the ceiling”. What she assumed was another routine step in the long audition process turned out to be something else entirely. “I immediately called my parents afterwards just in tears,” she tells me. “That’s when it fully set in.”

Long before the emerald hues of Oz, Bode was a creative child in a small Midwestern US town where entertainment was something you had to make for yourself. She and her older brother spent hours drawing, filling time in a place where options were limited. “In such a small town, you kind of have to get creative,” she says. “There are not really many places to go.”

Her route into theatre followed this younger-sibling logic. Her brother started doing local community theatre, and when Bode turned eight, she joined him there. What began as a social outlet gradually became something more serious. And unlike many aspiring performers, her parents “were never discouraging”, she explains.

At 11, a car accident changed Bode’s physical reality, leaving her paralysed from the waist down. “People from an outside view think I thought it was over for me, but I never thought that,” she says. What unsettled her most was not the accident itself, but how others responded to it. “I felt it more strange that other people perceived me differently. They’d say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re still doing theatre!’ In my brain, I was like, ‘Well, why would I not?’”

She traces that reaction back to stigma. “People assume a lot of the time that disability is a death sentence,” she says, “or that expectations for what disabled people can do are a lot lower than what they actually are.” While there was a long period of physical adjustment and self-acceptance, giving up what she loved most “was never really even a question for me”.

That certainty was reinforced early on by the adults around her. When the accident happened, she was in the middle of a production. Instead of replacing her, the directors, Chase and Molly Stoeger, made a different decision. “They were like, ‘I don’t see why you can’t continue doing theatre,’” she recalls. “And also, ‘I don’t see why we can’t bring the show to you.’” They opened up the lobby of the children’s hospital and performed the show there. Years later, while filming Wicked, Bode sent them a long message thanking them for confirming what she had always felt to be true: that there was no reason a disabled person should not be able to do theatre.

Asked about the phrase I noticed she often uses in interviews when asked about her outlook — “I’m just sitting down — it’s not that deep” — she explains it came from a friend shortly after the accident. “They were like, ‘You’re literally the same person, just sitting down,’” she says. “And I was like, ‘That is exactly what it is.’” Still, she’s frank about the frustrations that come with other people’s assumptions: disabled people being “infantilised, spoken to like a child”, or excluded from social situations because others assume they won’t be able to take part rather than asking what accommodations, if any, might be needed. “I think that’s partially because they’re afraid of getting it wrong or maybe offending,” she says. “But I would always rather somebody attempt to include me than not be included at all.”

Fast-forward to her casting in Wicked. “It was very much a deer-in-headlights moment,” she says, explaining that panic soon followed joy when she realised she did not have a passport. “My mother is always right,” she laughs. “She’d been telling me all summer, ‘Girl, you need to get a passport just in case,’ and I was like, ‘No — I can’t afford to fly anywhere!’”

Heading to London to film for Wicked (and its second instalment, Wicked: For Good) became her first trip outside the US, and she remembers Hyde Park becoming a refuge on days off. “I liked that it was accessible,” she says. “I wheeled a lot through the park just to keep up with exercise and health.”

On set, the scale of the production was initially intimidating, but any nerves quickly faded. Bode admits she had worried about encountering egos behind the scenes. Instead, she found the opposite. Arriving on her first day, Erivo had left a box of pastels in her green room, a thoughtful nod to her love of art, while Grande had given her flowers. “They were both lovely,” she says. “I really am glad that [on] my first big project, the cast was kind. I think a lot of people assume celebrities give off a persona and then are divas or super mean behind the scenes, but it was nothing like that.”

It was the epic sets, however, that left the deepest impression. “Shiz University was probably my favourite,” she says. “The lake was really there. The ramp going into the courtyard was really there.” Coming from years of DIY community theatre, “these grand worlds were incredible.”

Being part of a largely queer cast also felt natural. “I love being surrounded by my people,” she says. “The world of Oz has always drawn queer people in — the whimsy, the fantasy. The saying ‘a friend of Dorothy’ wasn’t made for no reason.”

Bode’s journey with her own sexuality took time. For several years, she made coming out her New Year’s resolution, only to back out. It was only as she prepared to finish college that she decided she wanted to be fully known by the people she loved. “I don’t understand why anybody would look at a person differently for who they love,” she says. “It’s a small fraction of what makes a person a person.”

Today, she feels grounded by her relationship with her partner, Lauren, a fellow wheelchair user. Their shared experience, Bode says, brings a sense of ease. “There’s a specific understanding that disabled people just get about one another,” she explains with a laugh. While the public side of her work can be overwhelming for them both, communication remains central in their relationship. “We talk through it always, and we’re very good at communicating with one another.”

As her profile grows, Bode is increasingly labelled a role model, and it’s the reason why she leads the Future (Under 25) category, supported by Clifford Chance, of Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley. Nevertheless, it’s a title she approaches with modesty. “I think the best role models are the ones who just are themselves,” she says. “People can tell when you’re speaking from the heart.”

When asked what she’d like her legacy to be, Bode’s wish is a simple one. “Making an impact on my friends and family is enough,” she says, though she is also conscious of the shift she represents. Now that the curtain has come down on the two-part epic, she hopes the industry’s perception of disability has evolved.

Her advice to her fellow queer people, especially those living through precarious political moments, comes down to remaining hopeful. “Queer joy is a form of resistance,” she says. “Celebrate your queerness as much as you can. You are never as alone as it may seem.” She adds: “Just know that you truly are loved always, and that I love you and that I will always care about you.”

For this performer, Wicked is just the beginning. She is an actor, a singer, an activist, and someone who understands the power of being seen on their own terms. Marissa Bode isn’t waiting for a wizard to grant her a future; she is already building it herself, one authentic performance at a time.

The full version of this feature appears in issue 369 of Attitude magazine, available now.

Get more from Attitude