Outed veterans share harrowing stories of Armed Forces’ gay ban as memorial marks overdue ‘homecoming’: ‘Turns out I did count’

Decades after being outed and dismissed for their sexuality, RAF veteran Graeme Grady and Navy Wren Sharon Pickering are finally honoured at the UK’s first LGBTQ+ military memorial, cementing their fight for equality

By Callum Wells

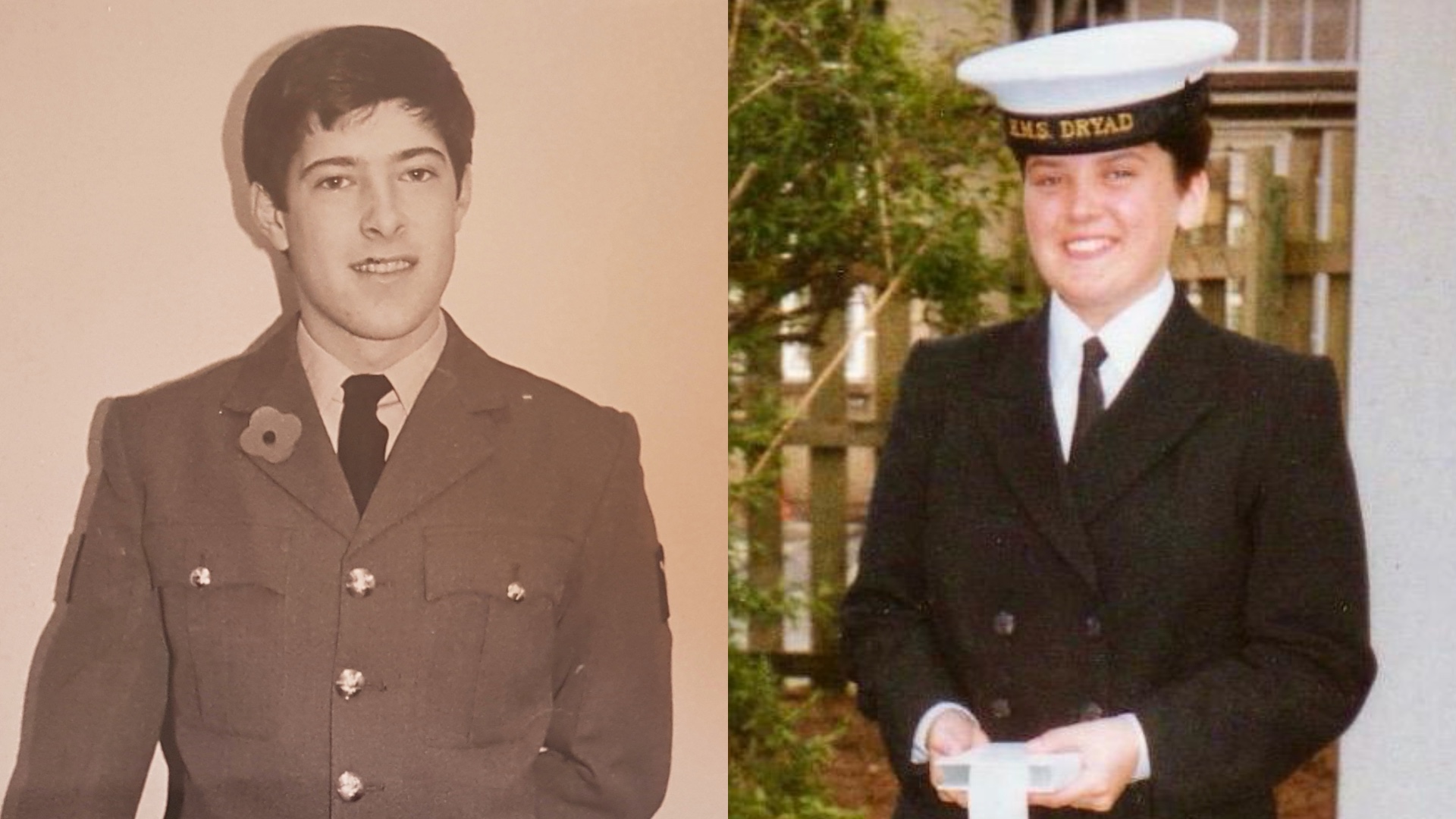

In the shadowed corridors of RAF Uxbridge in May 1994, Graeme Grady, a 30-year-old personnel administrator with 14 years of unblemished service, walked into what he thought was a routine briefing. Instead, it was a trap. Chaperoned by a warrant officer, he emerged hours later a broken man – outed, interrogated, and stripped of his career in the Royal Air Force. The questions weren’t just invasive, they were a violation. “Who did you sleep with? What did you do? How old were they?” And the cruelest cut; a probing implication about his infant son. That moment ignited a five-year legal inferno, one that Grady stoked alongside three fellow outcasts, culminating in a unanimous European Court of Human Rights victory in 1999.

Their case, Smith and Grady v. United Kingdom, didn’t just expose the UK’s military ‘gay ban’ as a breach of human rights – it forced its repeal in 2000, liberating an estimated 5,000 service members from a policy of shame, dismissal, and stolen futures. Pensions vanished, medals ripped away, lives unravelled. Grady’s defiance didn’t end the institutionalised homophobia that scarred the armed forces for decades, it carved a new chapter, one now etched in bronze at the UK’s first LGBTQ+ military memorial.

Unveiled on October 27 at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, the An Opened Letter memorial stands as that chapter’s quiet sentinel. It honours the incriminating notes, whispers, and suspicions that weaponised love against service. King Charles III‘s attendance at the dedication – his first major outing at an LGBTQ+ military event, and the first time a British monarch has engaged so directly with the queer community – bestowed royal weight on the reckoning. “That’s the highest compliment we could be given,” Grady tells Attitude, voice heavy. “For the LGBT armed forces community and the armed forces. The fact that the King himself is going to be there is just mind-blowing. It’s a real show of his dedication to all communities.”

Over 100 veterans, serving personnel, and allies gathered in raw emotion, a hard-won pride swelling amid calls from Fighting With Pride – the charity behind the memorial – for reparations and remembrance. In 2023, just three years after it was founded, its tireless campaigning won Rishi Sunak’s formal apology for the ban. In 2024, Fighting With Pride secured reparations – financial and non-financial – alongside a £350k Ministry of Defence fund to create and deliver the memorial.

Grady’s story anchors it, from the interrogation room’s glare to Strasbourg’s gavel, bridging the abyss to this week’s service. As the 61-year-old reflects on the unveiling, three voices from the Royal Navy and RAF illuminate the human toll – Sharon Pickering, a Wren (female member of the Women’s Royal Navy service) shattered in 1991; the serving RAF couple Sgt Antony Stafford-Boutwood and Flt Lt Jordan Stafford-Boutwood, whose 10-year marriage embodies the freedom Grady clawed from injustice; and Grady himself, the sergeant who turned personal ruin into policy’s undoing. “To lose it all of a sudden, I felt really bitter,” he recalls. “Wanted nothing at all to do with any of the services. I wouldn’t even buy a poppy.” Yet here he stands, a linchpin in history’s pivot.

“You’re gay, you must be a paedo. That’s the mentality you’re up against” – Graeme Grady on being investigated for his sexuality by the RAF

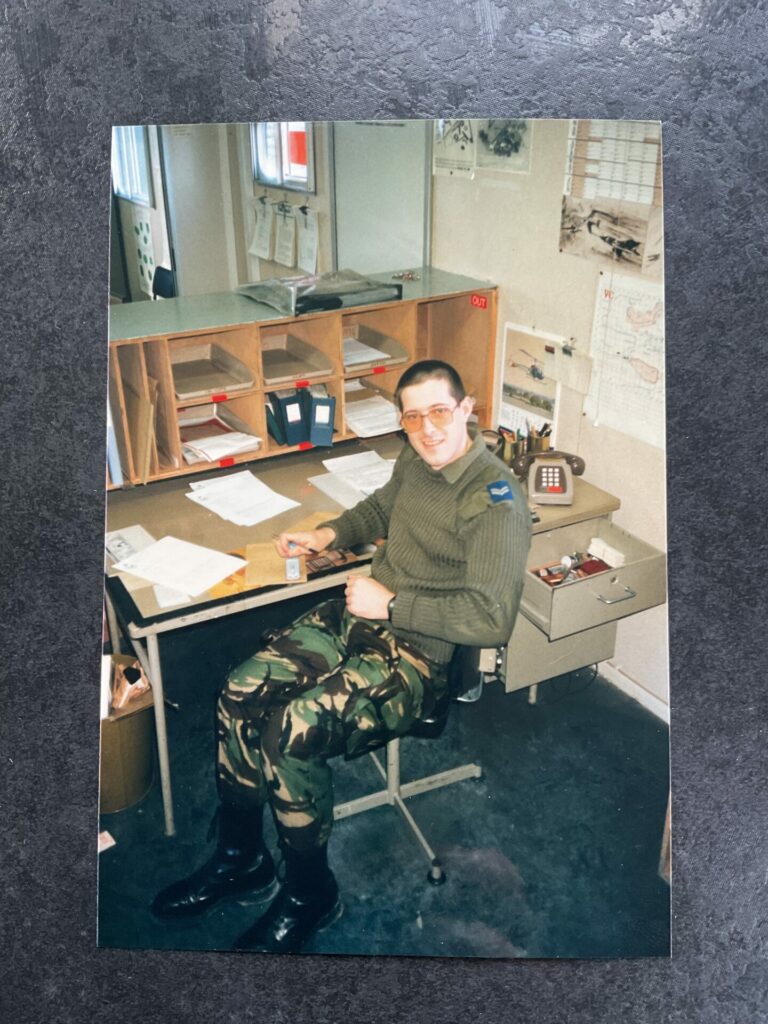

Grady’s path to that 1994 victory was far from the khaki lineage that propelled others. At 17 and a half, a stray newspaper ad snared him – no family in uniform, just raw impulse. “It was totally out the blue,” he says. “Nobody else in my family in the forces. I just thought, ‘Well, I’ll give it a go.’” His father wagered he’d bail early, but Grady logged 14 years and three months instead, a tapestry of pay office logs, drill instruction for fresh clerks, and classified murmurs in Washington D.C.’s embassy shadows from 1991 to 1994. “I loved all of my 14 years and three months… an amazing career,” he says, the warmth undimmed by hindsight.

But the internal war predated the uniform. Years of burying his attraction to men, convinced it was “wrong”, made acting on it feel like heresy. His employer’s blunt warning – “We don’t have homosexuals in the Air Force” – sealed the pact of silence, laced with the naive hope that the RAF’s male bastion might “cure” him. The inescapable reality of 80s homophobia, with slurs slung openly, even before senior officers, created a constant toxic hum. Near-misses sparked sweat, like a midnight yarn in a fellow flyer’s quarters up north. “Our reaction was, ‘Oh my God. Are they going to assume we’re gay?’”

A 1986 marriage provided cover for Grady, with children in tow, but at 30 in D.C., the seams split. His wife ferried the kids back home for a break; he met someone and the confession crested upon her return. “As soon as I met somebody I thought, ‘Okay, I need to end this marriage.’ I said, ‘Look, I’m gay.’ And she went, ‘Oh… that’s okay, you have your life now.’” An amicable divorce, timed for his impending pension, cleared space for a new chapter and a support group for married gay men beckoned. “Sounds a little rubbish to me,” he figured, yet showed anyway. But Grady’s attendance leaked through an army colonel’s tattle to his embassy overseer. Summoned to a 1:30 “briefing” that was no such thing, under PACE rules he was treated as a criminal. Grady sat with a silent colleague as witness. The accusation hit like shrapnel: “We’ve got proof that you’ve been seeing men in Washington D.C.” Denials crumbled under family probes – “We hear your marriage isn’t very strong” – and threats to “dig around, really get you going”. The stakes crystallised, admin discharge, career torched.

“Okay, I am gay,” he conceded. Then the deluge. Every intimate detail was demanded, from partners’ ages to specific acts. The depths? A sneer tying his sexuality to his son. “You’re gay, you must be a paedo. That’s the mentality you’re up against.”

“If you didn’t make it illegal, then people would have nothing to blackmail me about!” – Sharon Pickering on the British Armed Forces’s historic ‘gay ban’

He was discharged on December 17, 1994, a date etched in his memory. The digging dragged on – “Who in the Air Force is gay? What were their names?” – before he washed ashore in London: a rented room, temp office gigs morphing into 23 years in finance, then insurance. “It was about survival. I had to survive.” Family softened the blow, first coming out to his sister in 1993, who rippled the news to their mum, sparing him the pain.

“She was more upset for the children,” he recalls, although they didn’t bat an eyelid. His stepfather? “Is that it? It’s his life.”

Survival pivoted to strategy in November 1994, when Stonewall tapped Grady and three others – Jeanette Smith, Duncan Lustig-Prean, and John Beckett – for their spotless records. Their challenge targeted the ban’s core – a Cold War relic fearing blackmail, even post-1967 decriminalisation. Initial UK court losses stung, saddling Grady with over £100,000 in costs – the others shielded by legal aid. At the Appeal Court, Lord Bingham’s gaze met his: “Mr Grady, I’m really sorry, but I have to award costs against you. However, I would like to think that the government will not pursue you for these costs.” Grady had decided at the time, “I’ll give them a pound a week.” But deep down, had thought, “We’ve got to win this, we’ve got to win it. And I just knew we would win, but I didn’t know it was going to take us five years to win it.”

His determination paid off. The Strasbourg September 27, 1999, ruling was unanimous. The ban violated Article 8 of the European Convention – the right to respect for private and family life. The UK’s repeal four months later wasn’t grace, it was mandate, reshaping LGBTQ+ employment law across the UK and Europe. When offered a significant payout at tribunal, Grady defiantly turned it down, stating he would rather ensure the law was changed. His echo resounds in stories like Sharon Pickering’s – a nightmare that predated his by three years, a Wren’s ascent curdling into 1991’s rock bottom. From a military clan – her father a 22-year royal engineer, and sister wed to one – she hit HMS Raleigh in the late 1980s ablaze with joy. “I was so proud to join the Wrens. I took to it like a duck to water,” she recalls. Firearms training for the second Wren cohort, radar specialisation at HMS Dryad, she “absolutely loved it” and settled into Navy life “as if I’d always meant to be there”. Hockey, volleyball, a 21st-birthday victory – camaraderie was elixir. “You live, work, eat and sleep together. Only military people understand.”

The shadow first fell during a terminology class. “Dobie dust is washing powder, Jack is a sailor, Jenny is a female Wren, port is left, starboard is right,” the instructor had taught. “And, of course you all know it’s illegal to be gay in the military.” At 20, sensing her truth, panic clawed. “I’d never heard the term illegal used. I remember sitting there thinking, ‘Oh gosh. I’m a law abiding citizen, I’ve never done anything wrong. If you didn’t make it illegal, then people would have nothing to blackmail me about! You’ve actually caused the threat!” Rumours stalked her due to being older, shunning the NAAFI (Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes) bar’s drunken excesses, with no boyfriends. “If you were different, that difference labelled you as, ‘Oh, she’s probably a lesbian,’” she recounts.

“I hated the sight of me, that it meant I was going to lose my career” – Pickering recalls an attempt to take her own life

The first Special Investigation Branch probe came during training, sparked by a dorm chat misconstrued as her admitting leanings to shield another’s relationship. Interrogated by two male officers, she was asked, “Did I know anybody that was gay? Did I identify as gay? Had I had a relationship? Why didn’t I go to the NAAFI bar? Why didn’t I have a boyfriend?” Despite there being no evidence, the label stuck. Years later, a subject access request yielded nothing , with “no record of that interview… no taped interviews… disappeared”.

The whispers hardened into a first love that demanded disguise, a year-long relationship with Wren officer Maggie that Pickering cradled like contraband. On base, it was protocol’s mask – salutes exchanged, “Ma’am” murmured in uniform – but in the privacy of Maggie’s home, they shed the charade. “I absolutely adored Maggie,” she wistfully remembers. “I wanted to shout it from the rooftops but had to internalise all that emotion.” The toll mounted in quiet ways; stress visits to doctors who pinned her unease on having a “boyish appearance”, jotting notes that her short hair and jeans had invited the scrutiny, as if style, not statute, was the sin. “They said I didn’t ‘help myself’ with these rumours.”

Betrayal slithered in from the unlikeliest quarter – colleagues she trusted enough to call friend ran to the Special Investigations Branch with her secret. Her chief Wren, queer in solidarity, tipped her off. Pickering slipped a photo and her signet ring – initials laced inside with Maggie’s – into hiding. Then the net closed. Pickering was arrested and ferried to HMS Nelson’s stark interrogation chamber. “Two police officers came in. They read me my rights, they asked me if I wanted a lawyer. I said yes.” The advocate who arrived? A cipher in the chaos. “I didn’t know whether he worked for the Navy!” she exclaims. When he asked me if I was gay, I said, “No, no, no.” She held out through the initial barrage, only to be cut loose under “close arrest” with a shadow Wren trailing her every step, forcing her to spend her nights on the floor.

It all became too much to bear. Pickering recalls smashing a mirror, loathing the face staring back. “I hated the sight of me, that it meant I was going to lose my career.” A shard to her wrist followed, halted by her divisional officer’s grasp the next day, marks blooming like accusations. “You’ve got to tell them, Sharon, this is killing you,” she implored. The dam broke. What poured in was worse – a litany of lewd specifics from a rotating cast of interrogators, man and woman or two men strong, their probes laced with thrill. “How many times have you had sex? When do you have sex? What kind of sex do you have? How many fingers do you use? Did you have sex every night? Why not?” Her officer interceded once, voice cracking with outrage. “Enough’s enough. She’s told you, you don’t need to know this.” But the memories endure. “It was almost as if they were getting some kind of gratification. Those questions will just haunt me forever.”

“You might have thrown us out, but you didn’t destroy our relationship” – Pickering on her enduring friendship with Maggie

Shuttled immediately to HMS Sultan under wraps, she was severed from all kin and comrades, held “incognito and incommunicado”, petrified and alone. In a profound state of isolation, desperation offered a false avenue of escape in the press. Frantic for someone to tell her everything would be okay, Pickering contacted a tabloid newspaper, a choice she immediately regretted when the journalist proved intent on “selling copy”, not offering solace. The reporter arranged for hidden photographers and even tipped off the Royal Naval Provost, ensuring the Naval Police could capture the scoop on film to “sensationalise the story” into a two-page spread, despite Pickering explicitly asking them not to print it after their intentions became clear.

Detained in a Navy jail cell, she was thrown a copy by a petty officer, mocking, “Boy, are you famous.” Her world “fell apart”. The newspaper even ran a premium rate phone-in poll asking readers whether she should be dismissed, publishing the following week that 67% of voters agreed she should.

Tactics twisted sharper. A high-ranking Commander hissed at Pickering that Maggie’s husband was steaming home for vengeance, claiming, “We have to put you into protective custody.” Pickering knew Maggie had no husband, yet the officer’s conviction left her shaken, wondering, “Does she have a husband?”

In her final days, she was pressured to name others but the promise of leniency was a lie. “If I complied, there’d be a chance of me staying. I gave them names, a tactic I deeply regret falling for,” she dwells. “I’m still learning to forgive the 21-year-old who was fighting for her career.”

The final verdict was delivered at the Captain’s Table followed by the mocking offer of an “honourable discharge”. Maggie was expelled after her that December, yet, the bond they had built in secret endured. Now close friends, they linked arms at this year’s Pride, striding defiantly past Whitehall. “You might have thrown us out, but you didn’t destroy our relationship,” she declares.

“We are allowed to be ourselves” – Jordan and Antony Stafford-Boutwoods on being accepted by their peers

Grady’s firestorm, kindled post-Pickering, burned brighter. His win’s afterglow graces the the career of married couple Antony and Jordan Stafford-Boutwoods: Antony in engineering at RAF Brize Norton, Jordan in logistics, also co-chairing the RAF’s LGBTQ+ Network since 2023. Married a decade, they serve openly. “We are allowed to be ourselves,” Jordan says. “We can work together, live together, be happy.” Jordan’s Armed Forces Leader of the Year nod at the LGBTQ+ Defence Awards spotlights Pride badges, ally training – “visual shifts” for recruitment.

Antony, 2023’s Outstanding Achiever, mentors queer recruits. He notes, “We will all become veterans. It’s nice to sit there and go, ‘We have a memorial to really immortalise what we have all put into the armed forces. It does signify to those veterans that had a really awful time that they are remembered, they are part of our family. And now we’re progressing into a new era.” Through the Network, they’ve hosted events to “bring those veterans back into the fold… and become quite good friends with a lot of them,” Jordan adds, “making them feel part of that family once again”.

An Opened Letter traces from “shame and injustice to pride and recognition”, its folds no “crumpled” relic but an “opened” truth – beautiful, like a letter from home turned weapon. Pickering, who now volunteers at the Arboretum following a policing career in mental health, corrects the misnomer: “It doesn’t need a rainbow. It’s about something so beautiful.” For the 54-year-old, the unveiling feels like a “homecoming”, declaring, “For 34 years, I have denied that I was a veteran. This says that my service mattered.”

King Charles’s involvement adds weight, bittersweet for Pickering given the Queen’s Regulations behind her dismissal. She worries about momentum fading: “Is it all going to drop off for year 26? These stories shouldn’t be forgotten, commemorated every day.” Yet the Stafford-Boutwoods’ lives prove progress endures, with veterans like Pickering and Grady ensuring it’s remembered. “Turns out I did count,” Pickering echoes, reclaiming her place. In this opened letter, the armed forces – and our community – finally honour the truth: love serves, undismissed.

If you were affected by the gay ban between 1967 and 2000, please reach out to Fighting With Pride for support and assistance with seeking reparations.