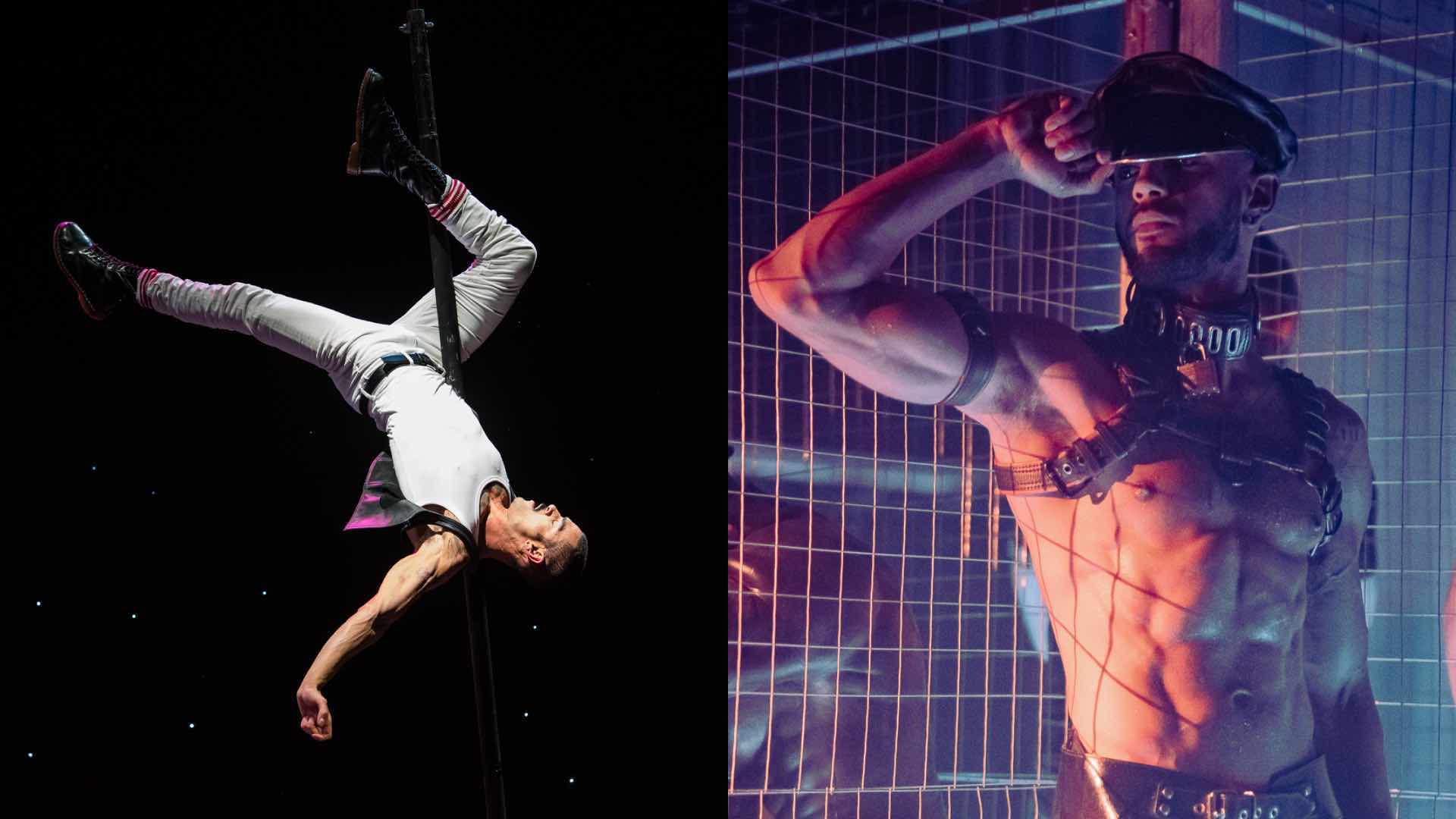

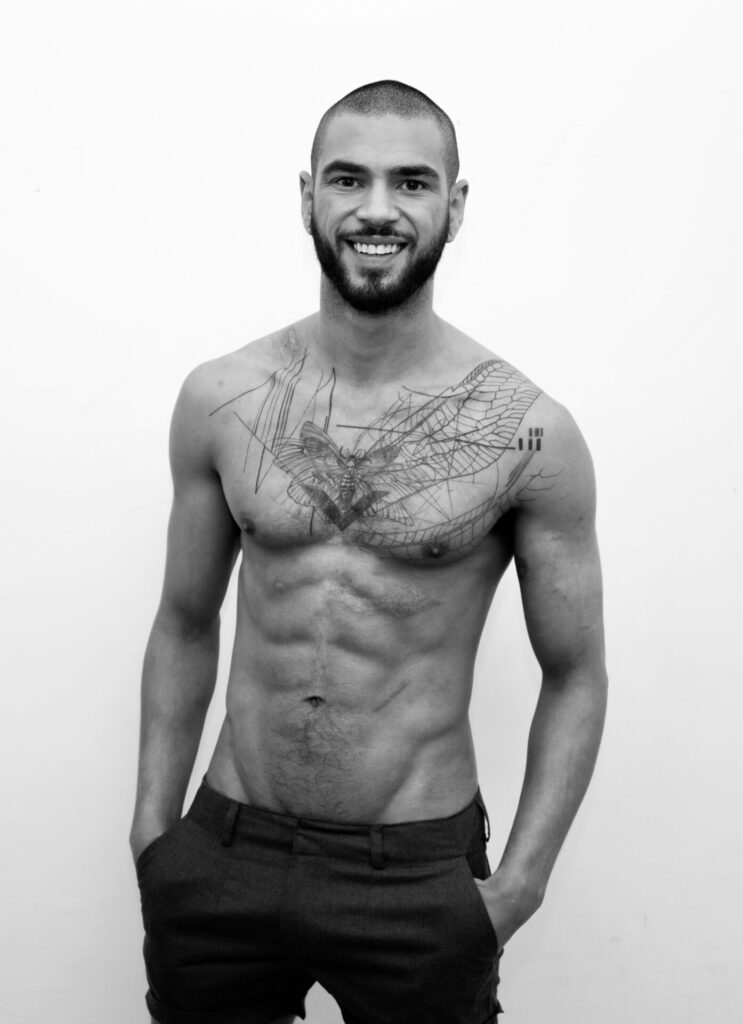

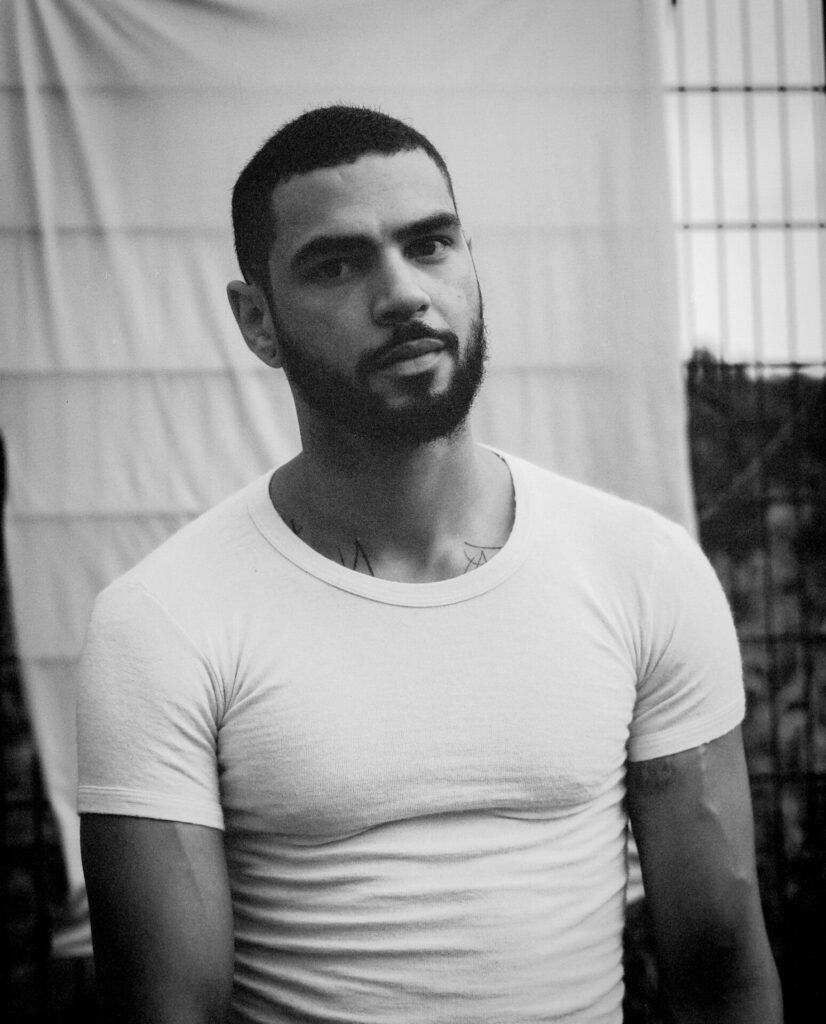

Sadiq Ali on the life of a circus performer living with HIV: ‘It’s more about where we are now, rather than where we were, or how’ (EXCLUSIVE)

"My way of taking control back over my diagnosis was by being obnoxiously loud," says Sadiq

By Aaron Sugg

“I don’t know who, where, what. I just know I got really sick,” Sadiq Ali recalls, his voice softening as he looks back on the day he learned he was HIV-positive 11 years ago.

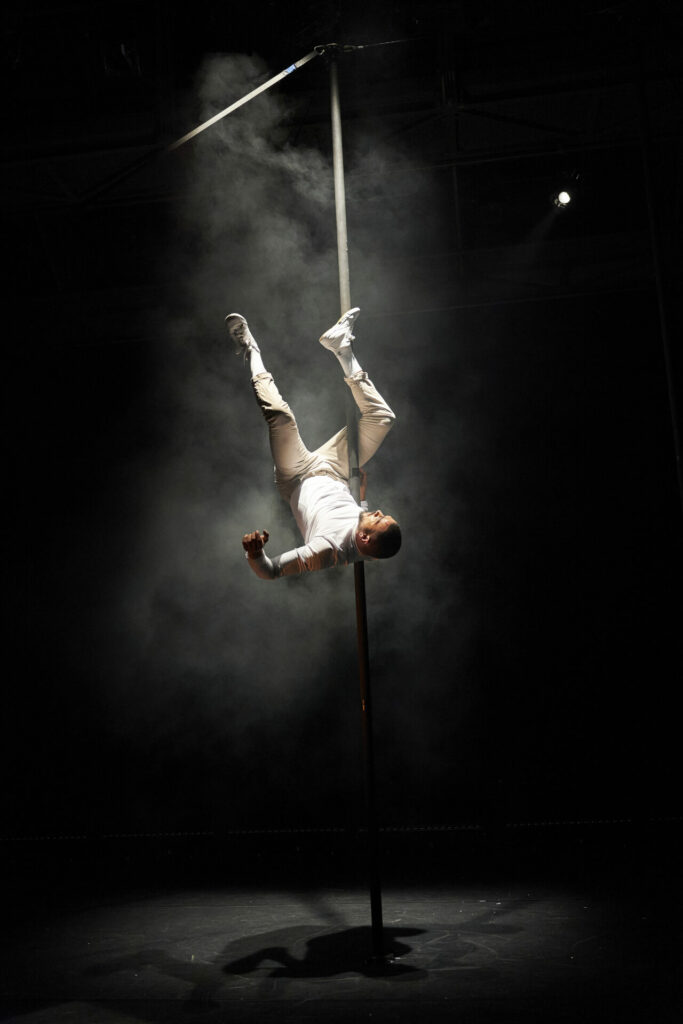

He brings me back to the beginning. “London Circus School, 2014,” he says. “I was diagnosed with HIV in my first year at circus school. And in circus, we work very physically with each other.” Risk, he explains, is woven into the craft. Cuts happen. Bodies bleed. This is the norm within his chosen family.

But when he was diagnosed, something in that family shifted. “I really noticed quickly people distancing themselves from me and not really talking about it.” For Sadiq, whose body is his instrument, his livelihood, his dialogue, having it suddenly become a site of fear, both his own and others’, was devastating. Yet for Sadiq, the story is not one of limitation but of reclamation.

Activism, he tells me, became a natural extension of that openness. “So my journey didn’t have a lot of personal shame in it. In fact, my way of taking control back over my diagnosis was by being obnoxiously loud. So ding campaigns with Terrence Higgins Trust and GMFA, and my friends at some point calling me the face of AIDS, which is a thing.”

“I became undetectable within a few months”

In this World AIDS Day feature, Sadiq reflects on the moment his life – and his relationship with his own body – shifted. A mixed-heritage, queer circus artist, he speaks with disarming honesty about trust, family and the demands of a profession where bodies collide, lift, catch and depend on one another.

On those closest to him, he speaks fondly: “I had a lot of people around me that made it very easy to be very open early, and I became undetectable within a few months.”

Sadiq remembers one moment with absolute clarity. “I was spinning in the air about five metres up, and I’d cut my arm,” he says. During his final performance, mid-trick, the injury opened again. “I bled all over the studio I was in.”

What happened next still surprises him. The same students who, months earlier, had been hesitant to come near him, leapt to his aid. There was no fear, there was no pause. “They were in there without hesitation,” he says. “They cleaned up my blood, put me in a shower, patched me up.”

“I’d accidentally created a cohort of allies”

In that moment, he understood why openness had changed the space around him: “I realised that by being open, and learning with young people who wouldn’t have interacted with an HIV story otherwise, I’d accidentally created a cohort of allies.”

When I ask how he contracted HIV, he hesitates… surprised. “That’s a very personal question.” And yet, in another intimate turn, he tells me that to this day he does not know, and does not wish to know, how he acquired the virus.

“I know I was having a wonderful time that I’m entitled to have,” he says of the life he was living before his diagnosis. He had just moved to London: a new city, new freedom. He plunged into a bubble of parties and sex, a life unburdened. But then came New Year’s, and with it, the sickness.

“I thought I was having the worst hangover of my life”

“I thought I was having the worst hangover of my life,” he recalls. “And actually what was happening was I was going through seroconversion, my body was fighting a virus off.” A few months into the new year, Sadiq got his results. He tested positive for HIV.

In a moving moment, he reveals that he does not know who, what, where, when or how he contracted the virus, and he does not lose sleep over it. “I’ve never really pried because that’s not what matters. It’s not what matters,” he tells me, opening my eyes. He lists the many possible transmission routes he encounters in his work: children born with HIV, people who acquired it through substance use, friends who contracted it through sex.

“I’m working on a show at the moment that’s trying to update the narrative into the present day,” he explains. The piece centres on a woman and her diagnosis, a deliberate shift in focus. “Because really, it’s not a gay men’s issue anymore. Statistically, as gay men, we’re not actually the biggest contractors at the moment, for the first time.”

“It’s more about where we are now, rather than where we were, or how”

For Sadiq, it’s not about the past, but about looking forward: “It’s more about where we are now, rather than where we were, or how,” he says. “It’s about who and what we can be for each other.”

Sadiq was outed at circus school. “It started to snowball,” he says. His vulnerability was twisted; friends and colleagues spread his diagnosis as a warning rather than in solidarity. He remembers feeling foreign in his own skin. “You can feel out of control of your body,” he says. And when the people around him were changing for the worse, and even his body no longer felt safe, the ground beneath him shifted. “When that’s taken away from you, that’s a really hard, hard time,” Sadiq remembers, emotion catching in his voice.

He reclaimed his body with unapologetic honesty. “It was a form of control. It was getting my own control back,” he says in a moment of self-development, love and inner peace. “Not because I’m diagnosed with HIV, but because I suddenly realised that I was mortal,” he tells me honestly.

Facing stigma is something Sadiq has battled for a long time, though admittedly it is getting a lot better. “I fortunately haven’t received the Grindr messages I’ve seen other people get,” he says. But even with transparency, those closest to him struggled with his diagnosis.

“Why didn’t you use a condom?”

Growing up in a Muslim family, having HIV, let alone being gay and queer, was a difficult development for relatives to face, not out of discrimination or homophobia, but through fear of the unknown. He remembers telling his sister. She is, as he describes her, “super open, super knowledgeable, super liberal.” And yet the moment the words left his mouth, fear overtook her. “Instantly she was like, ‘You’re going to die.’ She was crying, she was distraught.”

Then came the question: “Why weren’t you using condoms? Why didn’t you use a condom?” He realised how deeply certain narratives persist. “Statistically, it’s more women, Black women, and heterosexual men whose numbers are rising,” he explains. “And yet the message is still: why didn’t you use a condom? There’s a bit of slut-shaming that goes with contraction that shouldn’t be. And there’s this othering, a them-not-us kind of thing.”

He highlights the importance of chosen family – the LGBTQ+ community and the circus world – noting the cracks in understanding when you aren’t surrounded by people directly impacted.

“It applies to everyone and that it’s a global issue outside of being queer”

This World AIDS Day, Sadiq is campaigning for people outside the LGBTQ+ community to get tested. “It’s realising that it applies to everyone and that it’s a global issue outside of being queer,” he tells me. Highlighting Donald Trump’s political attacks on trans and AIDS healthcare funding, he asks what the future holds for people like him. “What does the future look like if all of that funding, all of that drive that we’ve had for the last few decades disappears? Does the future look more like the past? So that’s something that gives me a bit of a fire under my arse, that gives me my purpose here.”

It was announced on 11 November that the UK is cutting its pledge to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria to £850 million for 2026–2028 – a 15% decrease from the £1 billion pledged for 2023–25.

Growing up in a household of faith, Sadiq describes his early years as “quite tricky because there was a lot of contradictory messaging.” At home, he was taught one thing; at school, he learnt another; and with friends, something completely different. “That has taken me the best part of my adult life and I’m still working on unpicking what is me, what is what,” he reflects.

His HIV diagnosis became a lens through which he and his religious family could explore and process his identity. “I made a show about it because that’s what I do,” he says. The show was called The Chosen Haram which followed a gay Muslim man coming out, navigating a relationship, and discovering the underground London chemsex party scene. The show toured the Edinburgh Fringe and travelled internationally for two years, allowing Sadiq to channel his personal journey into his art. “After coming out the other end, I’m like, okay, cool. This is me now,” he tells me happily.

“I’ve met people who are queer and Muslim and they’re able to reconcile that. And I’ve met people who are queer ex-Muslim and say that they could never,” he reflects. “I’ve stepped back from faith or practising, but I don’t give a political view on it because I’ve met people living both sides happily.”

“If you’re not going to interact with me because I’m positive, I don’t want to interact with you either”

Now in a relationship, Sadiq speaks candidly about navigating gay dating apps like Grindr as someone living with HIV, and why he chose to be upfront about his status. “Ultimately, if you’re not going to interact with me because I’m positive, I don’t want to interact with you either,” he tells me firmly. For him, the last thing he wants is to have to educate someone mid-date or mid-hook-up. “It’s just there like any other stat of top or verse,” he says. The simplicity of apps allowing users to list their HIV status echoes the approach he’s taken clear, direct and without shame.

“World AIDS Day is important to me because… Miss Pageant, here she goes – the first time I publicly came out about my HIV, outside of school, university, outside of my family, was on World AIDS Day,” he says. It was 2014, within his first year of diagnosis, when he decided to share his story through a YouTube video. “I thought I was going to keep it going, but I’m so ADHD, it was a one-off.”

The video documented his mission to achieve something physically demanding while living with HIV: learning how to do a backflip in a month. “For me, the physical performance and showing people circus and achieving physical prowess is an instant combat to stigma,” he says proudly.

“Let’s bring out one that’s still alive”

In an emotional moment, Sadiq takes me down memory lane, letting me into his intimate memories of his first boyfriend. “Let’s bring out one that’s still alive,” he says softly, recalling being 16 or 17 and in a relationship with someone who was HIV-positive. “I remember how scared this man was to tell me.” That compassion has stayed with him. “I’m so grateful for encountering and learning acceptance and the teaching that they gave me at such a young age.”

Yet even the strongest of men still face their challenges. “This person had so much internalised shame and homophobia that 10, 20 years later, their life conditions were not that great, and they were self-imposed,” Sadiq says, looking up with tears in his eyes. “They were self-imposed because of social conditioning that told them that they weren’t worth it.”

Looking ahead, Sadiq is deep in creation mode. Having teased it earlier in our conversation, he is bursting at the seams to tell me: “I’m working on a show called Tell Me.” This new show centres on a woman receiving her HIV diagnosis, and what happens when she’s given the chance to confront herself through time. The show runs two timelines in parallel: 1980–1984 and the present day, “It gives her an opportunity, through a mirror, a lens, to have a conversation with the past,” he explains. Highlighting the mental impact of the disease, the upcoming play does not hold back, displaying the tender realness of “shame, her homophobia, internalised homophobia, her slut-shaming, her fear – she gets to face that like in a mirror.”

The project premieres in January, with performances scheduled at The Lowry in Salford, The Place in London, Worthing Theatres and in Edinburgh, before heading to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. “We’re in the rehearsal room at the moment,” he says, “and it’s starting to look real juicy.”

Subscribe to Attitude print, download the Attitude app, and follow us on Apple News+. Plus: find us on Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, X and YouTube.