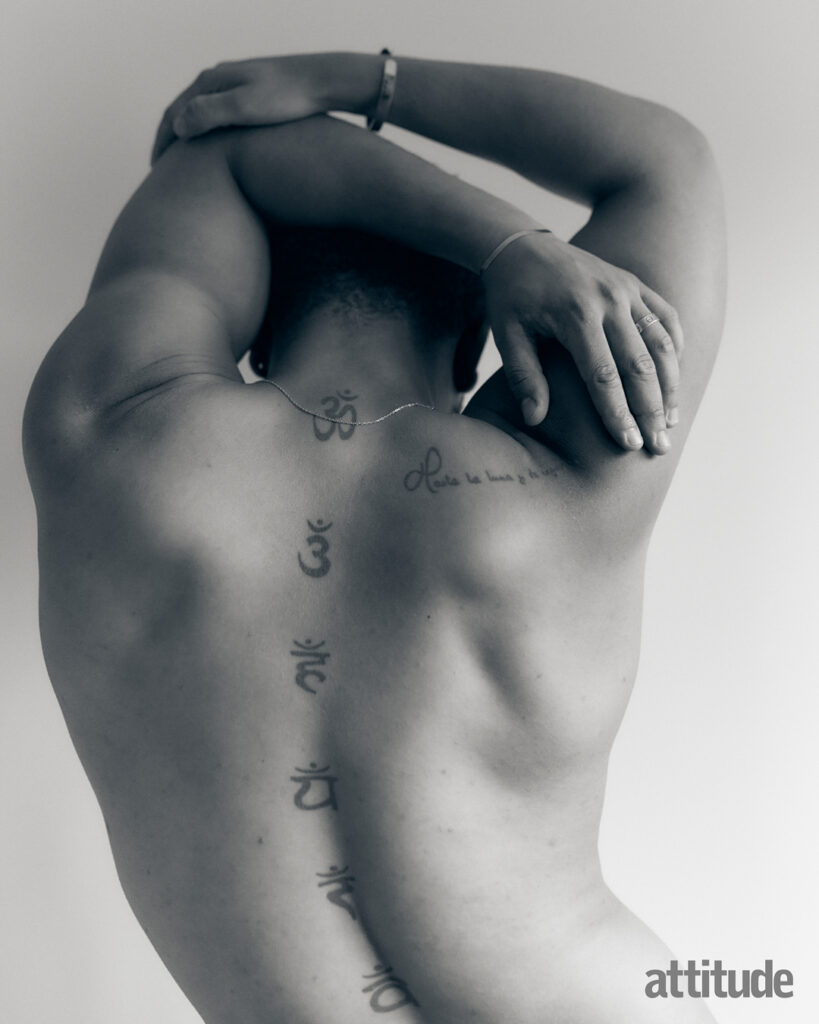

Real Bodies: Eight pics from podcasters Faris Haddadin and Josh Winter’s intimate Attitude shoot

As the first couple to feature in Real Bodies, the pair share how their contrasting upbringings – from Faris’s Middle Eastern roots to Josh’s mixed heritage in Reading – shaped the way they see themselves

On their frank podcast Avoiding My Anxiously Attached Boyfriend, hosts Faris Haddadin and Josh Winter share their personal experiences — both as individuals and as a couple — as well as the stories of guests like I Kissed A Boy’s Dan Harry and What It Feels Like For A Girl actor Alex Thomas-Smith.

Here, as we spotlight two people in an Attitude Real Bodies first, we learn how Josh and Faris helped each other feel more comfortable in their own skin…

Faris

My childhood was split between Jordan, where I was born and raised until I was nine, and Hertfordshire, where I continued my studies as a teenager. I would say that both places had a profound effect on how my body image developed.

Middle Eastern families tend to really care about the way you and your body look, and they won’t be shy to tell you if you’ve gained some weight or you’re not looking your best. I think this culture in my family definitely contributed to me developing a lot of insecurities and body dysmorphia. Coming to England as a child, I noticed that many people here, especially the older generation, are not dissimilar. I would often hear my nan making comments about people being fat or overweight, so, in many ways, I was getting it from all angles.

“The thing that I noticed most coming to the UK, however, was that such a big deal was made about me being brown and hairy”

Back in Jordan, my aunties or uncles would say, “Oh, you’re getting fatter. You need to lose weight,” to me and my sisters. I can distinctly remember moments in my childhood when I realised that I was bigger than my cousins. I would be wearing different clothes to them, or maybe I’d be able to borrow a T-shirt from an adult, and it would be just slightly baggy on me, not how it ‘should’ be.

The thing that I noticed most coming to the UK, however, was that such a big deal was made about me being brown and hairy. I remember a lot of comments being made in school about how hairy I was for my age, remarks about me being able to grow my tache before a lot of people my age and how hairy my arms were. As I grew older, I lost some weight, so thankfully that wasn’t as much of an issue in my teenage years, but people would say things like, “God, you’re hairy, aren’t you?” Or things like, “Are you that hairy everywhere?”, as well as some racial comments or slurs.

Josh

I grew up in Reading, as the son of a white British woman and a Sierra Leonean man. Throughout my childhood, my mother was my primary caregiver and my entire family was white, and so, my complicated relationship with my body has always centred much more on how I felt othered from my white family members, than a fixation with being too fat or too thin. As a child, I began to notice key distinctions between myself and the people closest to me. My skin was a different colour, my lips a different size, my nose a different shape.

“My friends of colour were an invaluable resource to me as I came into my own”

It was my Afro hair, however, that caused me the most pain. Many mixed-race people possess a head of light, manageable curls. I, however, was blessed with a mane of strong, kinky, quintessentially West African hair. Trips to the hairdresser became a frequent source of dread in my life. While my white siblings would sit down for a quick 20-minute trim, my mother struggled to find a barber who was experienced with dealing with the texture of my locks. The options seemed to be either sit and endure the pain of my hair practically being ripped out of my scalp by someone who had no idea what they were doing, or have my hair shaved off as short as it could possibly go by my mother at home. Attempts to transform my hair into something more manageable with the use of relaxers were usually in vain, and soon haircare began to feel genuinely traumatic, like the ultimate representation that I was different to everyone around me.

Although I wasn’t necessarily growing up in a multicultural household, thankfully, I did have a diverse group of friends around me in school in Reading. My friends of colour were an invaluable resource to me as I came into my own, always available to answer the questions that I might have, and serving as an important reminder that other Black people exist. I eventually found a barber that specialised in cutting Afro hair who could help me shape and look after it, though I still opted to keep my hair cut pretty short as I felt my Afro drew attention to the fact that I was different.

After I finished school, I had opportunities to travel which were also helpful in me coming to understand both my racial identity and sexuality. I began to experiment with different hairstyles, from cornrows to dreadlocks to growing my Afro out.

This is an abridged version of a feature that appears in issue 366 of Attitude magazine, available to order online here, and alongside 15 years of back issues on the free Attitude app.