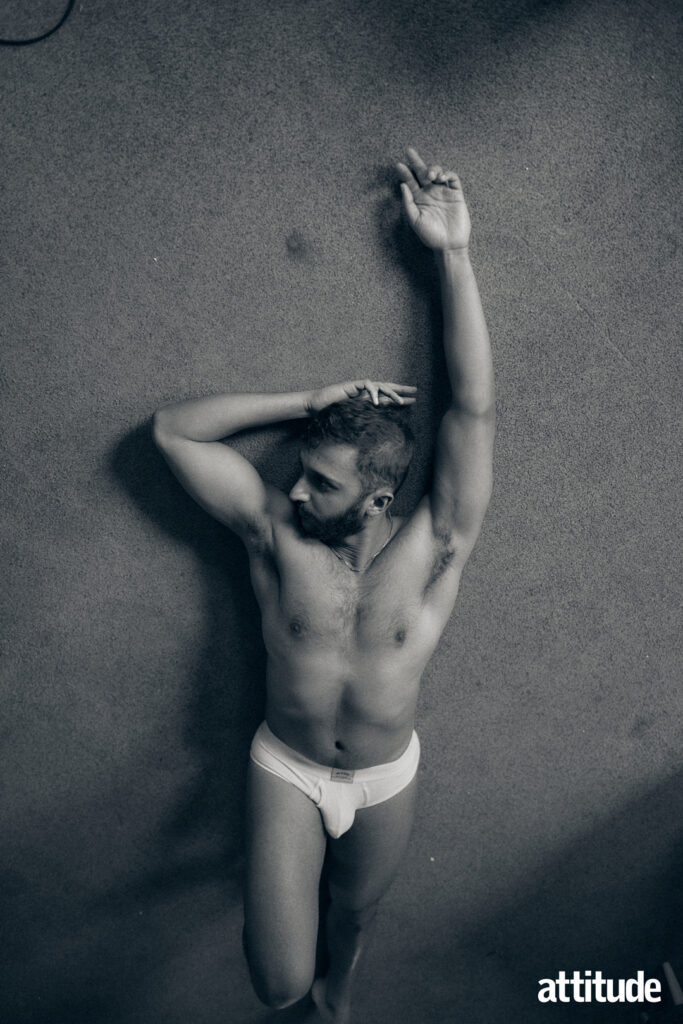

Mufseen Miah touches on stigma, chronic pain, and more in exposing Real Bodies shoot

Mufseen Miah shares his story about growing up as a queer South Asian in the UK and his experiences with chronic pain

I grew up in a big and loving Bangladeshi family in Brighton, one of the most diverse and welcoming cities in the UK. But being a second-generation immigrant, I always felt one step removed from it. As a result, my childhood was centred within the Bangladeshi community.

School was a mixed bag. I went to a standard state school where you’d have children from all backgrounds, but the majority were white. I was an easy target just for being brown. Thankfully, bullying was mostly verbal and rarely physical. There was a lot of self-suppression. Usually I’d keep my head down and hang with a small group of friends during breaks. It was only when I got to college that the fear of bullies stopped. By then, studying and getting good grades was paramount for a chance of a happier gay life.

Life outside school revolved around the local mosque and seeing relatives. It was quite a sheltered life. I was told from a young age I couldn’t have tattoos, piercings, or even an ‘unconventional’ haircut. If I did, I was bringing shame to my family. I didn’t know who I was back then. To a certain degree, my hair, my clothing, and even my behaviour was policed by parents and religious leaders.

“The relationship I have with my body is forever evolving” – Mufseen Miah

There was a shift as I got older, when I started to make friends outside the community and ventured into Brighton’s gay scene. It was then that my world opened up. I learned I could choose what kind of life I wanted for myself. Living in Brighton was great for making new friends, and going to parties and concerts was important for me to express myself in ways I couldn’t at home. I’d also regularly walk along the promenade to contemplate how my life fits together, being gay but also Muslim. Some habits don’t go away; I’m still a huge fan of long walks and music to calm myself.

I know how difficult it is to be proud when all you’ve been taught is to feel shame about yourself. So I’m always inspired by queer people who choose to live their lives proudly, with full acknowledgment of their culture, sexuality, and gender expression. Dye your hair, get a piercing, have top surgery, or get a hair transplant. At the end of the day, we know our own body the best. These forms of self-expression can’t be underestimated because when our body reflects our true self, it brings so much joy.

The relationship I have with my body is forever evolving. When I first started exercising, I thought if I got ripped like the guys in porn, I would get their success. The London dating scene can be a particularly brutal place for South Asian men, as I found out. I had the motivation to get a better body, but it was all for external validation.

“I’ve had people judge me on so many fronts”

I think it’s difficult to be a gay man and not have insecurities about your body. Between dating apps, social media, and porn, there’s definitely a focus on certain body types over others. I’ve had people judge me on so many fronts. There have been guys who thought I was attractive until they found out I was South Asian. I’ve had people say I’m not fit enough, and oddly some who’ve said I’m too fit.

I can shrug these comments off now, but when I was starting to date, I didn’t have a thick skin, or the same level of confidence. It really got to me. It made me feel less than in many ways. People come out to be liberated, but within the gay community you can still feel ostracised for not looking a certain way. It takes longer to find your safe spaces and navigate through it all with your body confidence and self-confidence intact.

As queer people, we’ve been through a lot of personal and communal struggles, so we don’t have the luxury of living in ignorance. I think most queer people have a keen and critical eye because we’ve had to in order to survive. But it’s a bit of a double-edged sword when it leads to self-criticism. I could stand in front of a mirror and easily criticise every single part of my body. Is my nose too big? Do I have a lazy eye? Why can’t I grow more chest hair?

“Self-criticism isn’t just internal, it’s informed by societal racism, homophobia, and Eurocentric beauty standards” – Mufseen Miah

For me, that self-criticism isn’t just internal, it’s informed by societal racism, homophobia, and Eurocentric beauty standards. In my early twenties, I had an issue with my nose being too big. I joked I’d get a nose job. There’s nothing wrong with my nose, but at the time I just felt inferior for not having a smaller, straighter, European nose. It’s so difficult to not compare myself to what I see in the media. That’s why diverse representation is so important for everyone’s mental health.

A turning point for me was when I suffered from alopecia barbae for a second time as a result of being overstressed. I started getting bald patches in my beard again, and the only thing I could do was shave my beard off. It was a big blow to my self-esteem. I felt somewhat emasculated not being able to grow a beard anymore. It wasn’t helped by people on social media commenting on my new hairless face. I’m naturally quite a reserved person, so I didn’t want to disclose my condition to everyone.

I sported a moustache for a while, which put a smile back on my face, but then people made comments about that too. In the end, I just had to let it go. It’s just hair. Despite feeling very personal, it really shouldn’t be that deep, and there are definitely more important things in life. When it comes to comments on my body and appearance, I only care for the opinions of my chosen family — people who have context and who care for my wellbeing.

“Every sketch, painting, and sculpture I have posed for has added to this mental montage of what my body looks like”

When I was 19, I was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, a form of spinal arthritis. Effectively, my overactive immune system attacks my joints, causing inflammation and pain. I remember thinking that this had come at the worst time, just when I was starting a new life at university, away from the watchful eyes of my parents. Most mornings I would wake up early to make sure I had extra time to stretch and let pain relief medication do its thing. On the worst mornings, I’d have to take codeine before even getting out of bed as the pain was too much to bear. I felt hopeless, alone, and a failure.

Every day that my arthritis flared, I hated my body a little more. This continued for a few years until I got the right medication. When most people start to build a relationship with their body, I was already enemies with mine. It has taken years to undo the self-hating talk. But I don’t look back thinking I was robbed of experiences anymore. Instead, I’m grateful the doctors were able to identify my condition earlier. It means I can have the best quality of life possible. A huge part of my motivation when it comes to exercise, travelling, life modelling, and the social media content I post stems from being a chronic pain sufferer. I don’t see my body as a hindrance but as a force that’s propelled me into pushing my own boundaries.

As a case in point, one day in 2018, I signed up to be the model of a life-drawing class. I don’t know exactly why because up until that point, I absolutely did not like being naked in front of people. When I was at school, I would write fake permission slips to get out of PE, just to avoid the locker rooms. But now I found myself in my mid-twenties wanting to shake things up and force myself out of my comfort zone, and that involved being naked in an empty north London pub. I had all these worries, but thankfully it was all professional, and I only had to focus on staying very still.

The whole experience was very meditative as I was suddenly hyper-aware of my body in a different way. I wasn’t there to look conventionally attractive, and no one cared if I looked skinny, average, or toned. I was just there to be still. Since then, every sketch, painting, and sculpture I have posed for has added to this mental montage of what my body looks like through an unbiased lens. It’s helped me to build a truer relationship with my body. And it’s only because my body and health have been such great teachers in life that I’m able to work towards improving understanding of queer issues and encouraging queer joy in others.

This feature with Mufseen Miah first appeared in Attitude’s March/April issue – out now.