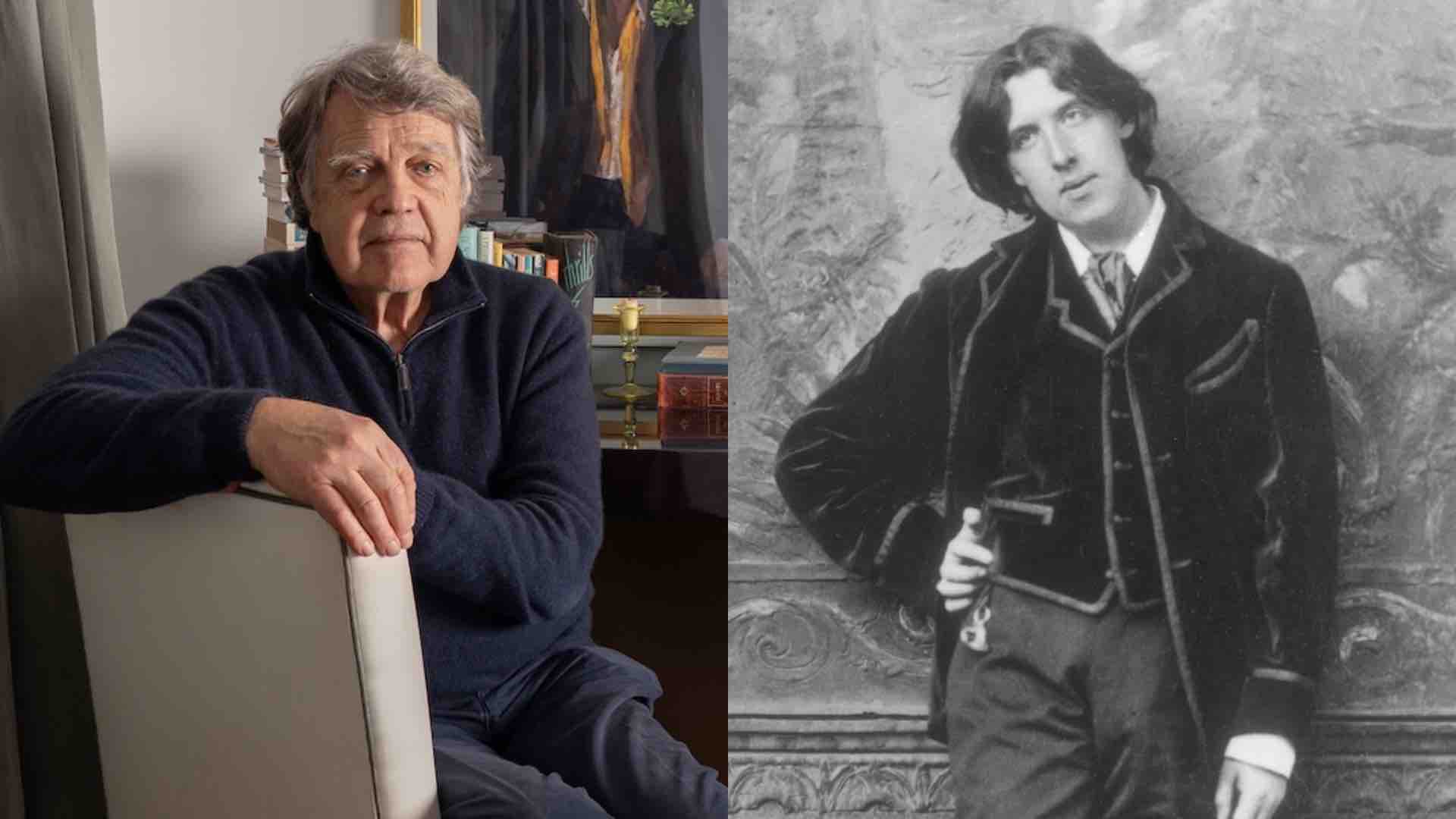

Oscar Wilde’s only grandson Merlin Holland on his new book After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal (EXCLUSIVE)

"The fact today he has become an icon for the gay movement is fantastic," Merlin tells Attitude from his grandfather's former home in London’s Chelsea

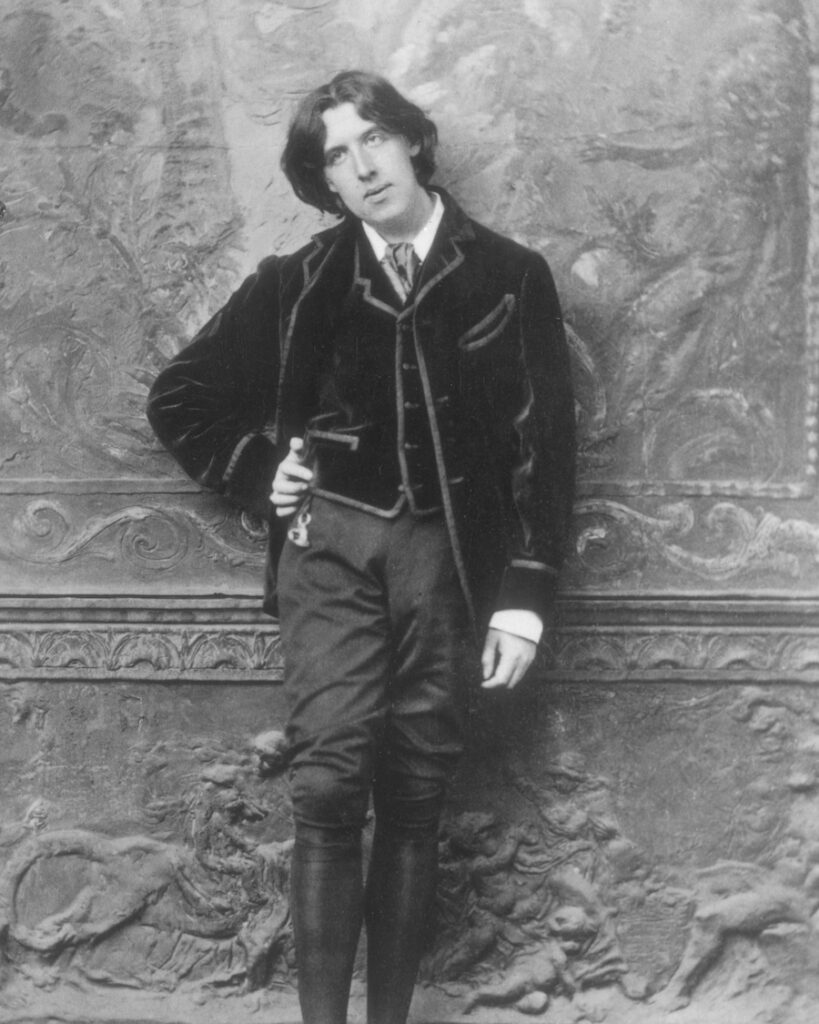

The last time Merlin Holland came to this particular address on Tite Street in London, a previous home of his late grandfather Oscar Wilde, was in 1954, at the age of nine, for the unveiling of a blue plaque. But neither Holland nor his relatives ever set foot inside the front door. It is only now, over 70 years after the blue plaque unveiling, that Holland has finally entered the very room in which Wilde wrote his only novel, the demon twink/twink death bible The Picture of Dorian Gray. The occasion is in large part thanks to the hospitality and planning of the house’s current tenant and Wilde fan Jen Elliott-Bennett. As Holland’s latest book about Wilde, After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal, is published, I am delighted to share this surreal moment with him.

I start by asking for his most prominent memory of the plaque unveiling. “Opposite, there was a children’s hospital where I’d had my tonsils out!” he laughs. “All the nurses had a grandstand view!” Later, at a lunch ceremony at the Savoy, according to his father, Holland signed people’s menus with “aplomb”. “I came back to school, and my headmistress wrote to my father and said I was absolutely poisonous and had been boasting about being at a posh luncheon and so on!”

Oscar Wilde’s blue plaque was unveiled at 34 Tite Street, Chelsea, London, in 1954

Among those to turn down an invite to the unveiling was the “very discreet” novelist E.M. Forster. Sir John Gielgud, the actor and theatre director, was set to unveil the plaque “but was arrested for cottaging. He could have got away with it, were it not for an Evening Standard court reporter, so it was all over the late afternoon edition of the Standard. He had to withdraw. He wrote to the committee and said: ‘I’m terribly sorry for what’s happened, but I think it’s better I don’t do it.’”

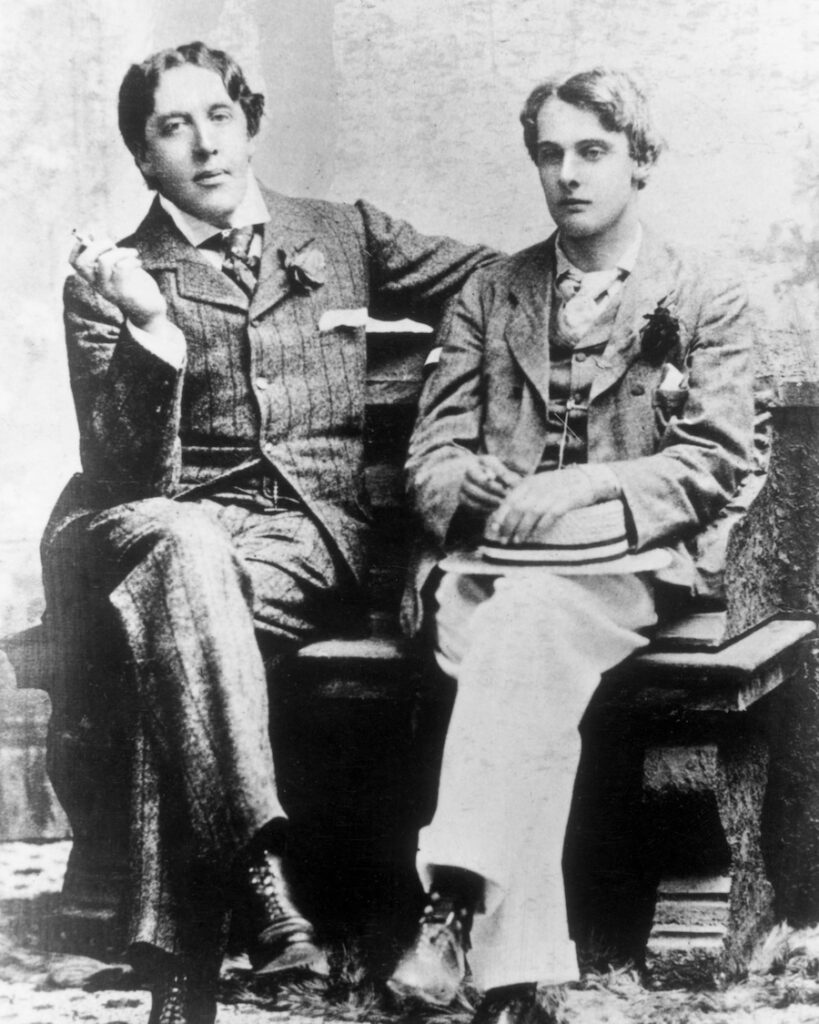

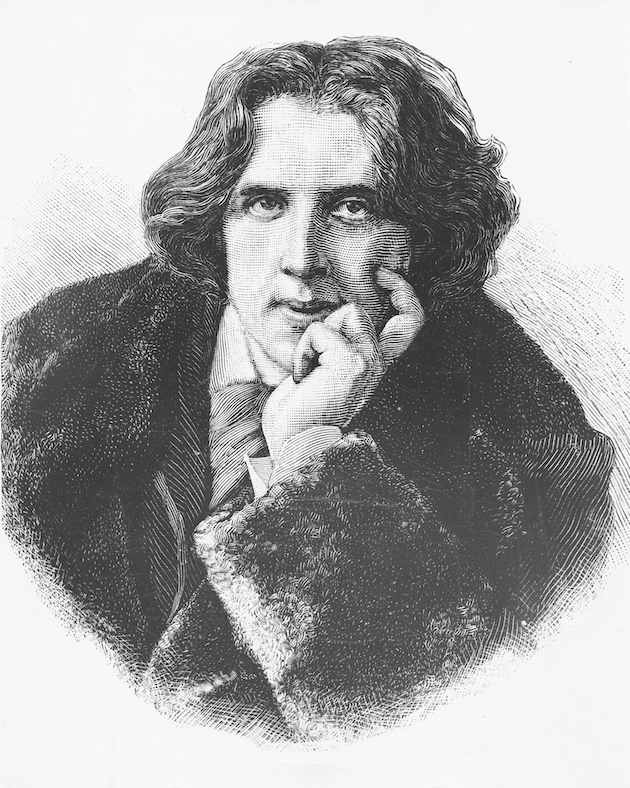

Gielgud’s story, sadly, converges with Wilde’s. At the height of his popularity as a playwright and bona-fide 19th-century celebrity, in 1895 Wilde was prosecuted and sentenced to two years’ hard labour for “gross indecency” over his romantic and sexual relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas, or “Bosie”, the son of the Marquess of Queensberry. Wilde was released from prison in 1897 and lived his final few years in exile, before dying of ear infection-related meningitis in Hôtel d’Alsace in Paris in 1900.

“A lot went on here. Happiness and unhappiness” – Merlin Holland on Tite Street, where Oscar Wilde lived

Back in Tite Street, there’s a heavy, palpably bittersweet energy in the air – can Holland sense Wilde’s presence here, I ask him. “I’m not a passionate believer in the supernatural – but I’m not an unbeliever,” he replies. “It certainly doesn’t feel particularly comfortable.” He reflects: “This is where the downfall started. A lot went on here. Happiness and unhappiness. For me, they cancel each other out.”

Now 79, Holland was born 45 years after Wilde’s death. I’m intrigued to find out what impact being Wilde’s grandson has had on Holland’s life. “Briefly, it’s as much a burden as it is an honour. I haven’t had any difficulties living with it, [other than] people expect me to be a reincarnation and prance about in a silly waistcoat.” More importantly, he says: “I didn’t want to make my name on the ruins of Oscar’s fame. The only way to feel comfortable with it was to join the spectators on the outside of the monkey cage.

“My father said he sometimes felt like a bear – people thrusting a bun at him through the bars of a cage on the end of an umbrella”

Of his journey with the surname Wilde, he simply says: “I don’t have it. My father lived with the name Holland from 1895 when his mother [Constance Lloyd] had the name changed [following Wilde’s imprisonment] to protect the children. [Vyvyan had an older brother, Cyril, who died in 1915 during the First World War.] For my father, it was travelling through life under a pseudonym. It was protection.”

By the mid-70s, Holland’s ancestry was sufficiently well known that he began to receive Oscar Wilde fan mail. “Secretary of the undeliverable fan letters!” he jokes, with the whimsy of his forebear. “Touching beyond belief, some of them. What do you do? Put them in a drawer? No. You reply nicely and say: ‘I’m so glad it meant something to you.’”

“My father last saw his father when he was eight,” he adds, meaning any conversations between them about Wilde revolved around “the latest film, or the latest biography. It wasn’t out of any sense of shame. It’s simply that my father’s memories were what he put in his book in 1954 [Son of Oscar Wilde].”

The main reason that Holland is fairly sure that he is the first member of his family to enter Wilde’s former home at Tite Street is because his father kept diaries “from 1941 right through to his death”, he says. “Had he come into the house, he would have said so. I think he just didn’t want to do it.”

“It’s not really about Oscar and his lifetime; it’s about what happened after his death” – Holland on After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal

Holland says his father’s diaries were “an immense help” when he was doing research for After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal, which is described as both family memoir and a cultural history investigation. “It’s not really about Oscar and his lifetime; it’s about what happened after his death,” he explains.

The new book has had a warm reception. “I’ve been frankly astonished by the amount of emails I’ve had from people who have got copies of the uncorrected proof,” he enthuses. “David Hare, Stephen Fry — who I saw on Saturday in [Oscar Wilde’s play] The Importance of Being Earnest [at the Noël Coward Theatre].”

Holland delivers his verdict: “[It’s] the most glorious camp-fest you could imagine. At the end, all the characters, production staff and stagehands come on stage dressed up as flowers. Stephen’s flower decoration is three times the size of everybody else’s!”

As a relative of Wilde, Holland is naturally entitled to give his opinion on productions of his grandfather’s works, as well as the various films and works of art he has inspired. Holland speaks highly of Fry’s turn in 1997 biographical drama Wilde, and of Rupert Everett, who played Wilde in 2018’s The Happy Prince. “Rupert’s is very moving,” he opines, comparing portrayals. “Stephen has the intellectual quality, the physical stature, the whole demeanour. But I felt it was a little bit downbeat. I think he was playing it [with] the knowledge of what was going to happen. Jude Law in that film was the best Bosie ever!”

“He had sympathy for the poor, the disadvantaged” – Holland on Maggi Hambling’s A Conversation with Oscar Wilde sculpture

Holland also rates Maggi Hambling’s A Conversation with Oscar Wilde sculpture, which features a bust of the playwright emerging from the end of a granite bench on London’s Adelaide Street. He shares how he had a hand in choosing it. “I sat on the committee to select [a public sculpture of Wilde]. I remember Kenneth Baker [by then an ex-Tory politician], who was also on the committee, saying: ‘A low-level sculpture that’ll attract all the drug addicts, drunks and layabouts of the Strand.’ I came straight back at him and said: ‘That’s exactly what Oscar would have wanted!’ He had sympathy for the poor, the disadvantaged, the persecuted. He’d love the idea that they came and sat and talked to him.”

I share that Wilde has “talked” to me, having played a role when I came to terms with my sexuality as a teenager. Holland says he “absolutely” hears such stories all the time — including from Rupert Everett. He remembers Everett telling him that he “always felt the odd one out at school. He’s now 66. It was reading and understanding Oscar Wilde that had helped him.”

“The fact today he has become an icon for the gay movement is fantastic” – Holland on Wilde being a praised figure in LGBTQ+ history

Conversely, it’s odd to consider that the gay icons’ gay icon may not always have been held in such high regard as he is today. “In the past, there have been elements of the gay community who have said Wilde set the cause back by years because of his behaviour,” Holland explains. “[They’d say]: ‘Had he been more discreet, less open, things might have changed earlier.’ It was just a brief period in the 80s when people were wanting to say a contrary view of the whole thing.

“The fact today he has become an icon for the gay movement is fantastic. He would be both proud and pleased and realise, too, that his sacrifice hasn’t been in vain. He writes in Dorian Gray about ‘the pathetic uselessness of martyrdom’. If you’re a martyr, you go willingly to your death for what you believe in. I think had Oscar been prescient, had he known what the result of suing the Marquess of Queensberry [John Sholto Douglas, for criminal libel in 1895, after Queensberry accused him of ‘posing as a sodomite’] would be, I don’t think he would have done it. His art to him was everything.”

This is an excerpt from a feature appearing in Attitude’s January/February 2026 issue.

Subscribe to Attitude magazine in print, download the Attitude app, and follow Attitude on Apple News+. Plus, find Attitude on Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, X and YouTube.