LGSM members on the ‘true manifestation of allyship’ between LGBTQ+ people and miners in Thatcher’s Britain (EXCLUSIVE)

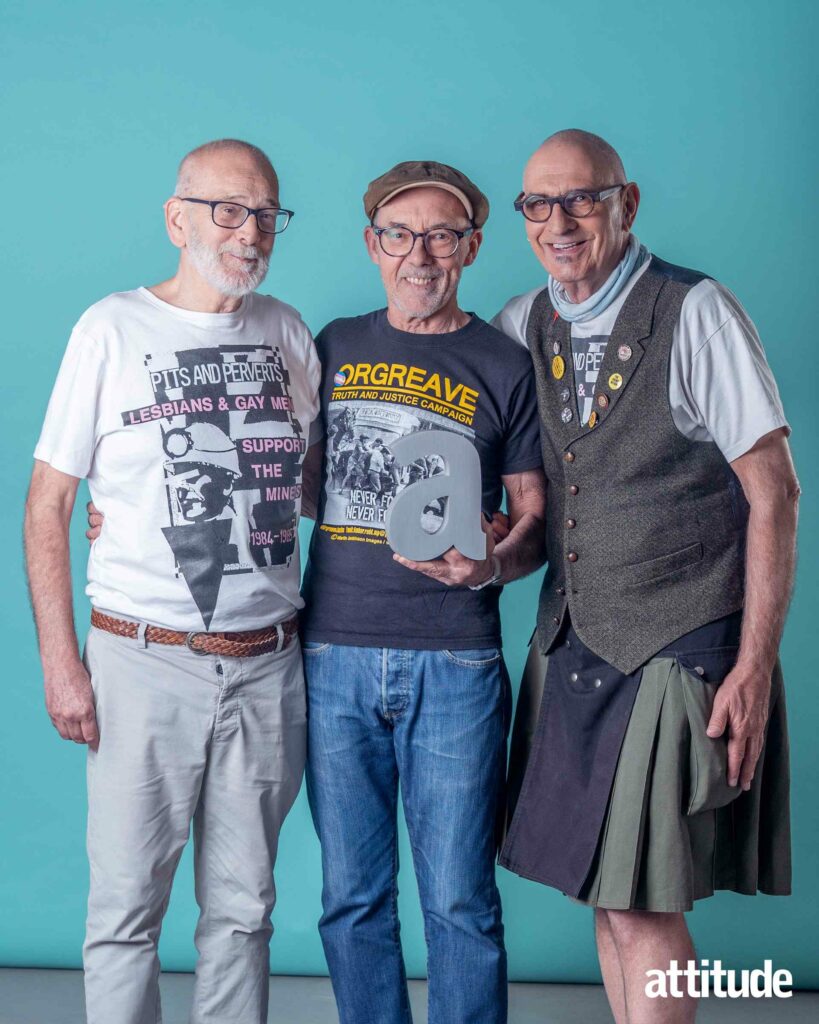

The incredible efforts of the people who set up Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) have been honoured at the PEUGEOT Attitude PRIDE Awards Europe 2025, supported by British Airways

By Dale Fox

“We didn’t care what they thought of us — we just wanted to help.”

That’s how Mike Jackson, co-founder of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), sums up the radical spirit behind one of the most powerful — and unlikely — alliances in British political history, which is this year being honoured as a winner at the PEUGEOT Attitude PRIDE Awards Europe, supported by British Airways.

LGSM was founded in London in July 1984 by Jackson and Mark Ashton, two activists who became inspired after attending a talk by a striking miner. As the Thatcher government escalated its assault on coal miners, and queer communities faced mounting discrimination, the pair grabbed collection buckets and headed to that summer’s London Gay Pride march.

“We had absolutely no rights. The Labour Party weren’t listening, and the unions weren’t listening. So, people started forming autonomous groups and kept banging on the door until someone eventually did,” Jackson tells Attitude.

For queer people in the 1980s, visibility often meant risk. The press was hostile, the police were violent, and the AIDS crisis was only just beginning. Jonathan Blake, one of the first people in the UK to be diagnosed with HIV, joined LGSM after meeting fellow activist Nigel Young. “I’d just received my diagnosis,” he says. “Anything that kept me from thinking about it was incredibly important… It was an adventure, because this was unknown territory.”

Regular fundraising outside London’s Gay’s the Word bookshop soon snowballed into something more profound. When LGSM members visited Onllwyn in South Wales — one of the mining communities they’d been raising money for — the power of the alliance came into focus.

“We walked into a packed miners’ welfare hall and the whole place fell silent,” Jackson recalls. “We didn’t know what that silence meant. Then one person started clapping. And then everyone stood and clapped. We were not expecting that in a million years.”

“The women in the community played a huge role in helping the men see past the stereotypes” – Mike Jackson, LGSM

For queer activists used to rejection, the kindness they received was unforgettable. “Right from the outset, we were offered mutual solidarity,” says Jackson. “We didn’t educate them — that sounds patronising,” he adds. “But many of them hadn’t knowingly met gay people before. And the women in the community played a huge role in helping the men see past the stereotypes.”

Over the course of the strike, LGSM raised more than £22,500 — the equivalent of over £85,000 today — to support striking families. The funds paid for food, fuel and a minibus. The miners even had “Donated by Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners” painted on the side of the bus, complete with a pink triangle.

“We never expected anything in return… It was, ‘We will support you because you need our support,’” Gethin Roberts, a core organiser of LGSM, explains.

One of the most powerful moments of the alliance came at 1984’s Pits and Perverts benefit concert at Camden’s Electric Ballroom, headlined by Bronski Beat. Organised to raise funds for striking families, the night brought together thousands of people — queer activists, miners, trade unionists — in a show of unity few could have imagined just months earlier.

On stage that night, Onllwyn miner Dai Donovan made a moving address to the crowd: “You have worn our badge ‘Coal Not Dole’ and you know what harassment means, as we do. Now we will support you.”

Then came 1985’s London Lesbian and Gay Pride March, when the miners turned up en masse to proudly march alongside LGSM. “We weren’t expecting it,” Blake says. “It was emotional. You have to pinch yourself that that really did happen.”

Later that year, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) backed a motion supporting LGBTQ+ rights at the Labour Party Conference — a shift that helped pave the way for legislative change. “It was building on work that had been happening for several years within trade union movements,” Roberts says. “But the breakthrough was getting a really big, important blue-collar union like the NUM on our side — that tipped the balance.”

Blake adds: “[It was an] absolute true manifestation of allyship and what allyship can do and can achieve.” That solidarity endured long after the strike. When Mark Ashton died of an AIDS-related illness in 1987, miners travelled to London to attend his funeral.

“What’s happening to trans people today is a carbon copy of what happened to gay people 40 years ago” – Mike Jackson, LGSM

The remarkable story of LGSM might have faded into footnotes if not for Pride, the 2014 film that introduced their story to a global audience — or the upcoming musical that will do so again. What keeps the story alive, the trio agree, is how it speaks to the challenges facing the queer community now.

“What’s happening to trans people today is a carbon copy of what happened to gay people 40 years ago,” says Jackson. “The ridiculous arguments, the obsession with toilets. It’s just plumbing and construction, for fuck’s sake.”

Blake adds: “Nobody learns. The language attacking trans folk is exactly the same as it was for gay people in the 60s and 70s. It makes my blood boil.”

For all three, the message of LGSM endures because it was never just about what they achieved alone. It was about what can happen when allies stand together in solidarity.

“Queer people have always been a minority,” Jackson says. “And we always will be. So, we’ll always need allies.”

Roberts concludes: “It shows that activism can transform your own life. If people could be encouraged to get involved in activism — whether it’s about the climate or democratic rights — that’s a really important part of what the film has done, and what our story does.”