All of Us Strangers’ Andrew Haigh interview: ‘Everyone asked if I’d do a Weekend sequel – it didn’t make sense to me’

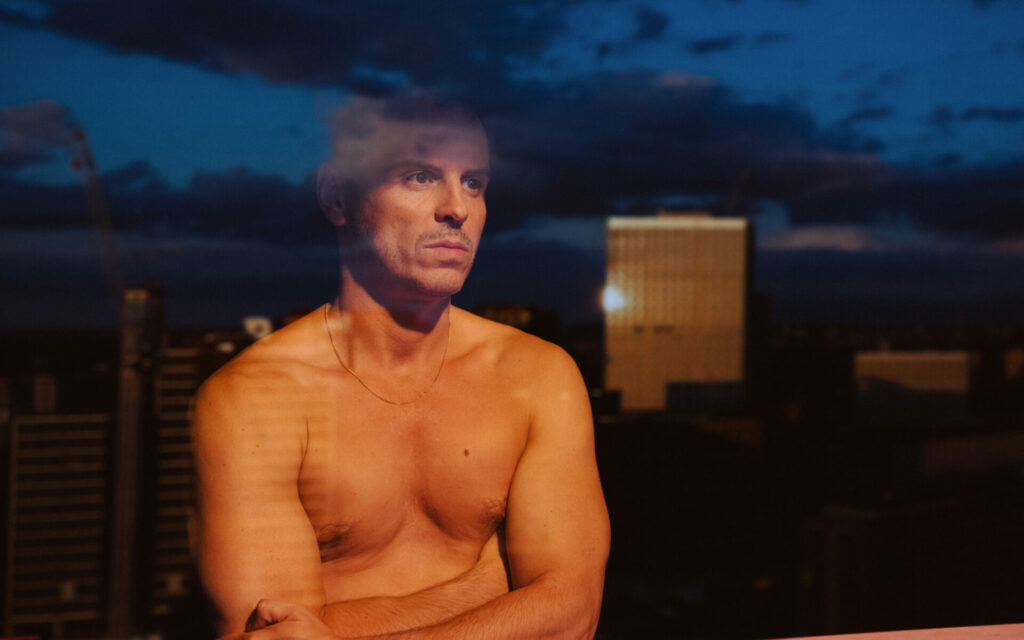

Exclusive: The director discusses with Attitude's Editor-in-Chief the journey from the emotional intimacy of his breakthrough film to the visceral intensity of All of Us Strangers

There’s a scene in Andrew Haigh’s new film All of Us Strangers that felt a bit like watching my own life in flashback. It takes place in the Whitgift Centre in 1980s Croydon, south London, where key parts of the film were shot. Also included is Haigh’s actual childhood home in nearby Sanderstead, where he lived until around the age of nine, before his parents divorced and he moved away. The scene in question lasts only a few seconds as a young boy (Adam) crosses the sombre shopping mall. But it was enough to transport me back to my own experience as a young kid growing up in the same London borough, a few years after Haigh’s time there.

In the 80s and 90s, Croydon felt like an incredibly oppressive place to grow up in. Head down there today, and you’ll find that the shopping centre hasn’t changed much, save that it’s largely lined with discount stores rather than the popular high-street names that once filled it. Meanwhile, the sense of alienation that comes with being a young person in this incongruous suburb tacked onto the southwest of sprawling megacity London feels hauntingly familiar.

“It’s those English suburbs, they’re very, very conservative. They always were,” Haigh says when we meet for our interview in Soho on an unseasonably warm autumn afternoon. “Back then, they were not a pleasant place for someone that’s different to grow up.”

In All of Us Strangers, young Adam is beginning to realise that his sexuality is setting him apart from the comforting familiarity of his beloved parents’ world. Sadly, this is not an experience unique to the 80s, but one that resonates with LGBTQ+ people even now.

“I did feel like my intention was to tell an experience of a very specific generation of gay men”

The grown-up, contemporary-era version of Adam is played by Andrew Scott. The Fleabag star plays a lonely gay man that is struggling to let go of the past in order to find happiness and move forward. One day, Adam meets the younger and far more outwardly free Harry — exceptionally played by Paul Mescal — who lives in the same apartment block. They begin an intoxicating affair that at last allows Adam a sense of connection and freedom he has denied himself.

You’ll likely know Haigh’s work from his 2011 breakout romantic drama Weekend, starring Chris New and Tom Cullen, which resonated with audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. Its frank depiction of an overnight affair between two gay men captured the attention of a community that responded well to seeing a sexual and emotional relationship being handled in such a refreshingly candid way on screen. The film’s commercial and critical success opened doors for Haigh in the US. HBO courted him to create Looking, the cult TV series starring Jonathan Groff, Russell Tovey, and Murray Bartlett. But it’s the intense and challenging All of Us Strangers that has propelled the director back into the spotlight.

“When I wrote [All of Us Strangers], I did feel like my intention was to tell an experience of a very specific generation of gay men,” says Haigh. “I think it’s been called by other people the ‘middle generation’, the generation of gay men that came into their sexuality, or came to understand their sexuality, while AIDS was affecting and killing so many people. So, you’re not in the generation before, who grew up coming into sexuality before AIDS, and you’re not in the generation who came after, where there is now medication, and it’s no longer a death sentence.

“We’re being told we should be happy. It doesn’t mean we are actually fully embracing who we are”

“Coming out in the 90s, in the shadow of AIDS and HIV, to be gay and to have gay sex equated with death, disease, and social isolation. I remember growing up thinking there was literally no future for me: ‘I cannot be a gay person in the world.’ That carries a lot of shame and a lot of self-hatred. It takes a lifetime to get rid of that,” he reflects. “You don’t have to scratch the surface very far to feel how you used to feel.”

While legislation may allow gay people greater equal rights, Haigh underscores that social attitudes are still a way behind. The wounds of growing up in the years post-AIDS are still raw. “Today, straight people have decided it’s OK now. They’ve decided that now we’ve got gay marriage, that it should be fine for us now. And they’ve forgotten how they used to treat us. We haven’t forgotten; we can still remember,” says Haigh, his calm and measured tone belying a defiant message. “We’re being told we should be happy. It doesn’t mean we are actually fully embracing who we are.”

On shame, Haigh highlights how it never just vanishes. “We’re supposed to have got rid of it, but of course, it still lingers. It doesn’t go away, but you can soften it and deal with it. But I also feel like that’s not necessarily a queer thing. Any kind of difference can make you feel isolated and alone. And lots of people have things that make them different.”

In terms of realising his own sexuality, Haigh remembers finding other men attractive as a kid. “There was always something about boys that I wanted to be around. I’d see a teenage boy and be like, ‘Why am I staring at that person’s hairy legs?’” says Haigh of those early impulses. On a trip to London, he was confronted with a poster about HIV featuring a man and a woman. “It was like, ‘Which do you prefer?’ I remember thinking, ‘I definitely prefer that picture of that man.’ It was the first time I really realised. It’s of no surprise that those things became connected.”

Closeting himself through school and university, Haigh had girlfriends to hide his identity. After university, he found himself living in London. ‘I cannot do this any longer,’ he told himself. “I was wandering around Soho after work looking in the windows of sex shops and wanting to buy a porn video, finally plucking up the courage to buy one. Then, sneaking it back to my flat and watching it and being like, ‘Oh my God, I know what it is that I want.’”

With his newly accepted sexuality, Haigh did what most gay men in the 90s did: he hit the scene, from Heaven to Popstarz and Wig Out at The Ghetto. “I remember going to G-A-Y in the Astoria and seeing what felt like a thousand gay people all in one room, and I was like, ‘Fuck. Oh my God, all of these people are like me.’ It makes me a bit sad that some people maybe don’t experience that now, because those things don’t exist in the same way.”

“I’m 12 or 13 years older than when I wrote Weekend. I’ve changed, and my understanding of my own queerness has changed and developed”

It was through London’s gay scene that Haigh came across his first film subject: an escort named Pete, who would become the focus of his semi-dramatised 2009 documentary film, Greek Pete. The film’s naturalistic style was the perfect precursor to Weekend, which felt relatable to so many gay men for its forthright take on love-at-gay-sight, and the giddy highs that come with exploring somebody new, and how you can give of yourself to them so unreservedly. “You have a chance, don’t you, to redefine yourself when you meet someone new,” says Haigh, “and you don’t have so much baggage that you have with friends and family. You get a chance to be like, ‘Actually, I’m going to say this thing about me or express this feeling,’ which you might not have ever said to anybody before.”

Arriving over a decade later, All of Us Strangers is viewed by Haigh as having a conversation with his breakthrough second film. “I’m 12 or 13 years older than when I wrote Weekend. I’ve changed, and my understanding of my own queerness has changed and developed,” muses Haigh of the two films’ thematic connections.

“I wanted to expand things that I had been thinking about for a long time. People had always asked if I was going to do a sequel to Weekend, and it just never made sense to me. Weekend is crazy because I had no concept that that film would be seen by people. Or, I think if I did know, I probably would have been more timid at the time about certain things.” Where Weekend may have been audacious for its time, the years since have allowed Haigh to fully release the restraints in All of Us Strangers.

There are many complex, intertwining layers in his universally lauded new film, All of Us Strangers: addiction, shame, grief. While they all pull at the characters, it never at any point feels excessive. Striking that balance was pivotal to making the film feel authentic. “I knew that it was about a lot of things all working together, and all of those things come from a similar place, essentially,” says Haigh. “The grief of losing a parent, the trauma of that, and also the trauma of growing up in a time, and the grief that your childhood wasn’t what you wanted it to be. I wanted the film to feel like there were so many things wrapped up together that linked to other things that can lead to addiction, that can lead to pain, to someone shutting down and not allowing anyone into their lives.

“They’re wrapped up together in a way that you can’t tell where the edges of all of those things are. They’ve all become this knot, essentially. What’s driving the film is the only way to soften that is to find people that care about you. And perhaps, more importantly, how you do that for other people. Adam and Harry, they realise that they need to do things for each other. That being there for someone else is as important as them being there for you. I think sometimes you can be quite selfish with love, expecting that you need to be loved, without realising you actually need to make sure that you’re giving that to someone else.”

“I think when you focus in on yourself, the past comes back. Relationships from the past come back”

The uncanny isolation of the characters is even more tangible seeing as the film was written during the Covid pandemic. “There’s an element of that, of being locked literally inside your house, but also into yourself. And I think when you focus in on yourself, the past comes back. Relationships from the past come back,” observes Haigh.

Another way All of Us Strangers sets itself apart from the director’s filmography is the unnaturalistic cinematography and vivid lighting that fills many of Scott’s scenes with Mescal. “I knew that the only way for this film to work was if it felt slightly shifted from reality,” says Haigh. “I wanted it to exist on a slightly different plane. You had to feel like you were somehow suspended. I wanted to be plunged deeper into some kind of psychological state.”

The actors are similarly beguiling in their roles. Mescal excels as Harry, bringing an effortless toughness and tenderness in equal parts. “I wanted this character to be someone who you felt like his version of falling in love was caring for that other person. That’s what you see unfolding. His version of love is: ‘I care about you, and I want to help you, and I want to know you,’” says Haigh of messy Harry. “Paul’s a really compassionate person. He genuinely cares about people, and is emotionally engaged in other people’s struggle. You feel that. His performance is really beautifully judged in terms of that.”

“There’s lots of sadness in All of Us Strangers“

Mescal was fully aware that the role would only work if it didn’t compete with that of his on-screen partner. “He’s a very generous person and a generous actor. He knew that this is a film essentially about Adam, and he’s a supporting role in that. That’s not easy for an actor. They know they are supporting, but they know they need their role to be important, too.”

Scott’s portrayal of Adam is similarly enthralling. The character’s inner conflict is tortured, and Scott pours himself into the role, but never once does it feel unwarranted. Scott plays Adam delicately in moments, then viscerally in others. “I know that he felt so connected to the material,” says Haigh of Scott. “When I started giving the scripts to people, they’d say, ‘This feels like it’s written for me and about me.’ And Andrew felt that. This is a film about the past bleeding to the surface. When you see it in Andrew coming to the surface, it’s genuine. It’s a beautiful performance, and it feels so real.”

Haigh applies a considered touch to the more intense scenes, which never feel like they’re being played for a reaction. In different hands, with a different actor, a different director, they could have failed. “There’s lots of sadness in the story,” says Haigh. “I was like, ‘OK, I want people to have an emotional reaction to it. But I don’t want them to feel completely manipulated into that emotion.’ You’re trying at every stage to work out, ‘Does this feel genuine?’”

From the older married straight couple played by Charlotte Rampling and Tom Courtenay in 45 Years (for which Rampling was Academy Award nominated) to All of Us Strangers, solitude and loneliness are consistent themes in much of Haigh’s work. If the British are renowned for their emotional reservedness, Haigh would be something of an auteur of the British condition on film.

Something the director is not shy to confront is how society also forces us to seek the comfort of others to mask loneliness. “We feel like that is the solution. But if you’re still hiding it, you’re still hiding it. And you can be very alone in relationships. You can be very alone with all of your friends,” he says. “But also the essence of being human is that we are essentially alone in the world. And our whole life is about dealing with that until the day we die, when you’re essentially alone again. It’s a greater existential question that will never go away, and we pretend it has. ‘Oh, no. I’m happy, everything’s great, we’re all good.’ We’ll buy things, we’ll do stuff, we’ll have fun. We’ll go and have a nice meal in a restaurant. It doesn’t escape the essential aloneness.”

On telling queer stories, Haigh is aware that LGBTQ+ people have been starved of on-screen representation for so long that people have a tendency to lash out at anything that either does not mirror their experience or presents them less than positively. “People can react with real vitriol, real hatred. I understand it when you’re desperate for representation, you want that representation to be you, essentially,” says Haigh about reactions to series like Looking or Russell T. Davies’ actually rather good Cucumber.

“I never want my films to be narcissistically about me. I’m not interested in that”

Haigh continues, “But it’s not you. It’s representing the person that’s made that show. It feels like that might be changing now. I feel like people are starting to be a little bit more compassionate to difference within the community, rather than it needing to be a strict representation of them.”

Part of these extreme reactions, Haigh says, is also down to the disparity between generations. “There’s a lot of anger from a younger generation against my generation. I’m like, ‘You’ve only just come out, please. We’ve dealt with our own shit.’ You just wish that everybody could realise that we’ve actually all been through the same fucking shit. We should as a community be supportive of each other. Even if we are very different and have different viewpoints on our lives.”

When it comes to those perspectives, there really is only one that Haigh can be responsible for: his own. It’s served him well. Over five remarkable films and his television work, he’s gradually unpicking what it means to be alone in a world that moves on regardless of our feelings, and what it also means to exist in the context of being loved in the same.

Haigh’s under no pretence that the medium of directing is a mirror through which he interprets his life. “It reflects my concerns, my ideas, my thoughts. I never want my films to be narcissistically about me. I’m not interested in that. But the films are an expression of how I see things,” he says as our conversation finds its natural conclusion. “It’s often what I find quite difficult, because [in terms of fame] I don’t want to be necessarily ‘in the world’. But I’m also making films that go into the world in a big dramatic way. So, there’s a tension there, and that triggers a lot of emotional things in me. But it definitely is, it’s a mirror, without a doubt.”

All of Us Strangers is in UK cinemas from 26 January.

This feature first appeared in the January/February issue, available now.